Brenna Clarke Gray

In the last few decades, literary scholars have increasingly “gotten serious” about comic books; ever since Art Spiegelman won the Pulitzer Prize in 1992 for his masterpiece, Maus, about his father’s experiences in the Holocaust and after, comics have slowly gained intellectual legitimacy. Indeed, the use of comics in Canada predates Maus. Some of the most significant names in Canadian literature—people like author Margaret Atwood and poet bpNichol—have throughout their careers played with comics as part of their larger body of work. Literary scholars have often paid attention when “serious” writers engage in comics, such as Carl Peters in his collection bpNichol Comics, or Reingard M. Nischik’s attention to Atwood’s comics in her Engendering Genre. But how do we analyze comics produced in Canada by comics creators? We now see comics appearing more frequently in college and university courses, including in Canadian literature classes. Yet the history, scholarship, and language of literary study do not always neatly transpose onto the world of comics. This chapter is designed to introduce new comics readers to the history of creating and evaluating comics in Canada and to the practice of reading them as scholars.

Comics have proven very popular amongst readers in Canada and the US since their beginnings in newspapers and comic books in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Gabilliet provides a concise overview of English comics from this period). Street vendors and tobacconists commonly sold comics alongside pulp magazines. Comics in English Canada went through a notable Golden Age between 1940 and 1947, a boom spurred on by wartime laws that cut off the import of American comics and that saw the creation of popular patriotic heroes like Johnny Canuck. However, after the war, the reintroduction of American comics drove the Canadian cartoons out of business (Bell 41–104; Gabilliet 463–67).

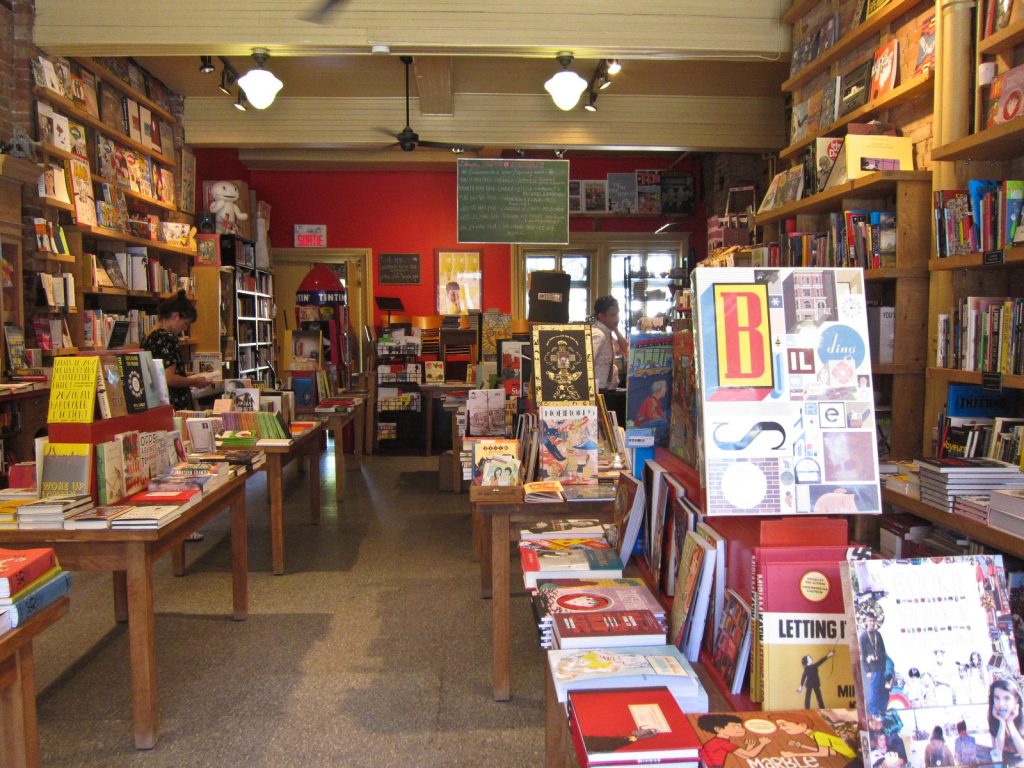

Drawn & Quarterly shop in Montreal. Jennifer Yin, CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr.

While comics were ubiquitous in popular culture, in the late 1940s and 1950s, parents, religious leaders, and politicians in Canada and the US grew concerned that some comics, especially horror and crime comics, inspired delinquency and illiteracy (Bell 87–104). Horror and crime comics were banned first in Canada and then in the US. From the 1950s to the 1970s, comics publishing in Canada almost came to a complete standstill, except for government-sanctioned educational comics, newspaper strips like Doug Wright’s Little Nipper (about a little boy and his misadventures), and the emergent phenomenon of underground comix.

In the late 1960s, comics began to make a comeback through small-press and self-publishing ventures (Bell 105–38). For instance, bpNichol published some of the first avant-garde comics through his own presses, grOnk and Ganglia, distributing them by hand and through the mail. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, self-publishing helped establish the careers of several notable Canadian cartoonists. For example, Dave Sim self-published his popular magnum opus Cerebus, (which started as a parody of fantasy comics starring an anthropomorphic aardvark, but which transformed over time into a platform for Sim’s increasingly antisocial political views) and other major figures like Chester Brown and Seth began by self-publishing as well.

Today, small presses like Coach House, Arsenal Pulp, and Conundrum also publish comics. Magazines and especially newspapers continue to play a significant role in supporting comic strips, both through mainstream syndicated works like Lynn Johnston’s For Better or For Worse, a slice-of-life comic about a mother and her family, and through non-syndicated contributions to smaller newspapers, such as David Collier’s comics (see Rymhs); both cartoonists have also released books collecting their strips. Furthermore, alternative newspapers like Vancouver’s The Georgia Straight have promoted unconventional underground cartoonists like Rand Holmes and David Boswell. Importantly, the Canadian comics publisher Drawn & Quarterly, founded in Montreal in 1990 by Chris Oliveros, has become a major locus of independent and alternative comics, helping to establish the careers of Chester Brown, Guy Delisle, Julie Doucet, and Seth. Drawn & Quarterly is now a cornerstone of alternative comics publishing in North America, alongside Conundrum, Koyama, Fantagraphics, Oni, and Top Shelf.

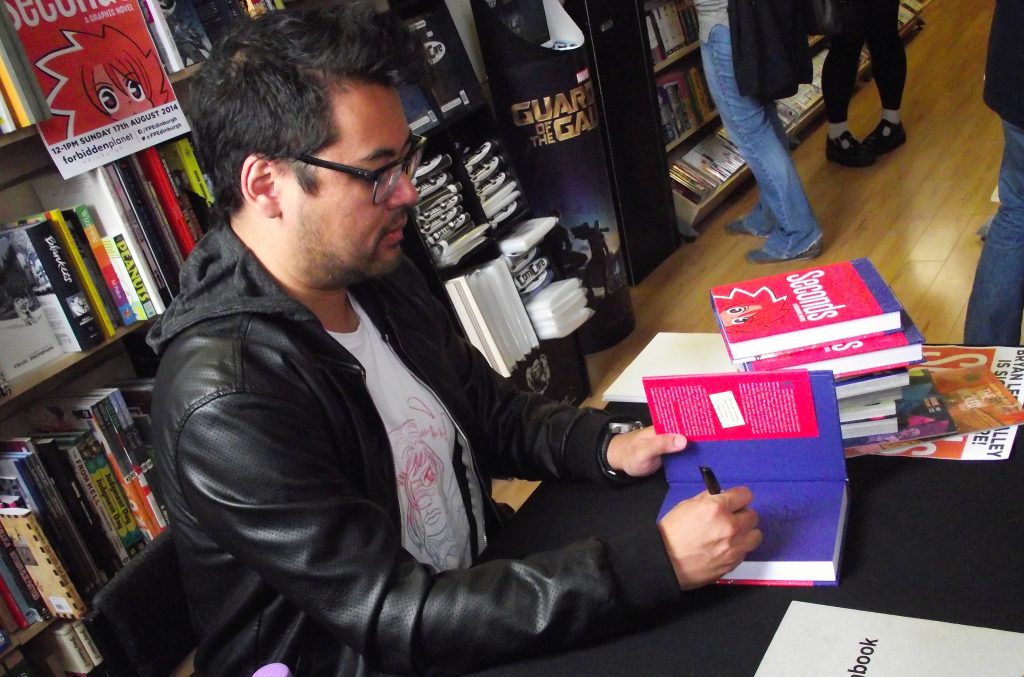

Bryan Lee O’Malley at a book signing in Edinburgh, 2014. byronv2, CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr.

Over the years, a range of alternative publishing institutions such as those listed above have helped develop and maintain the careers of a small cadre of cartoonists. However, with no large publishing houses in Canada, other comics artists went on to work instead with publishers in the US. One example is John Byrne, who after leaving the Alberta College of Art and Design without graduating in 1973 went on to become one of the most significant creators at Marvel Comics. Today, the dominant American publishing industry continues to attract and sustain Canadians, like the well-known cartoonist Jeff Lemire, who lives in Toronto but works for and publishes through American companies DC and Top Shelf, or Bryan Lee O’Malley, who lives in Los Angeles and published his popular Scott Pilgrim series through Oni in Portland.

This brief overview should help to orient you in the chronology of Canadian comics. As you progress through this chapter, you will learn more details about these historical moments, particularly as they relate to the scholarship of Canadian comics, and you will also be introduced to key debates and controversies within the field.

Questions to Keep in Mind While Reading

- Comics have, for much of their history, been considered a “low” art form. How might that value judgement shape the assumptions many contemporary comics readers bring to these texts?

- As you will see, the scholarship of Canadian comics is an emerging field. There might not be sources directly discussing a specific comic you want to research and write about. As you read a comic, consider where you might draw from other aspects of the study of Canadian literature to develop your own analysis (e.g., studies of literary representations of sexuality to analyze a comic’s representation of an LGBTQ+ character).

Works Cited

- Bell, John. Invaders from the North: How Canada Conquered the Comic Book Universe. Toronto: Dundurn, 2006. Print.

- Gabilliet, Jean-Paul. “Comic Art and bande dessinée: From the Funnies to Graphic Novels.” The Cambridge History of Canadian Literature. Ed. Coral Ann Howells and Eva-Marie Kröller. New York: Cambridge UP, 2009. 460–77. Print.

- Johnston, Lynn, and Katherine Hadway. For Better or For Worse: The Comic Art of Lynn Johnston. Fredericton: Goose Lane, 2015. Print.

- Nichol, bp. bpNichol Comics. Ed. Carl Peters. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2002. Print.

- Nischik, Reingard M. Engendering Genre: The Works of Margaret Atwood. Ottawa: U of Ottawa P, 2009. Print.

- O’Malley, Bryan Lee. Scott Pilgrim’s Precious Little Life. Portland: Oni, 2004. Print.

- Rymhs, Deena. “David Collier’s Surviving Saskatoon and New Comics” in Visual/Textual Intersections. Spec. issue of Canadian Literature 194 (Autumn 2007): 75-92. Print.

- Sim, Dave. Cerebus: Mothers and Daughters: Reads. Illus. Dave Sim and Gerhard. Kitchener: Aardvark-Vanaheim, 1994. Print.

©

©