The body of comics scholarship vis-à-vis Canadian texts is nascent but rapidly developing, and major contributions come not only from literary studies but also from a wide range of interdisciplinary perspectives. And because comics are a popular medium, their critical study often includes fan and audience response analysis. It is important to remember these unique contexts as you do your research. Casting a wide net is often helpful when searching for scholarly sources and research material. This brief overview of scholarship first introduces academic terminology for analyzing comics before examining how and why comics have come to be valued as scholarship and offering an overview of the critical landscape of Canadian comics.

Terminology

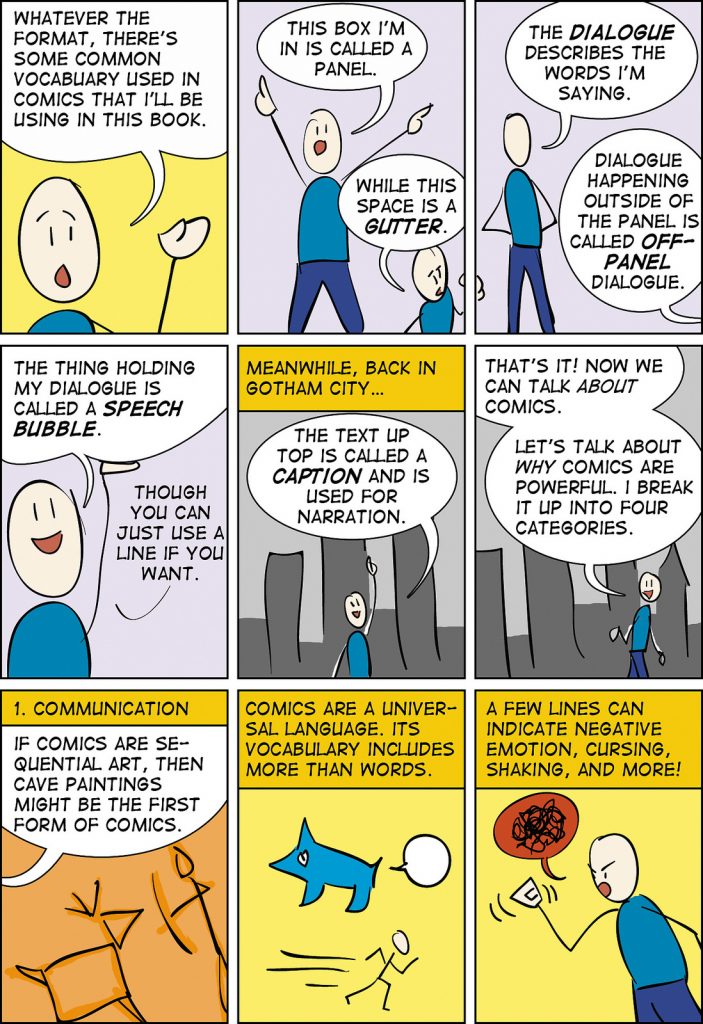

Comic 2.2 from Kevin Cheng’s See What I Mean? Rosenfeld Media, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

When reading and writing scholarship about comics, it helps to have the right vocabulary to draw on to describe what you are looking at. Most comics scholars now agree that “comics” is the most inclusive term for the medium. While you might hear the term “graphic novel” used frequently, it is problematic because (a) it is often inaccurate, like in the case of a memoir or other non-novel graphic text, inviting clumsy circumlocutions like “graphic novel memoir”; and (b) it has been historically used to create a high art / low art distinction in comics that separates certain comics from their larger history as a pulp, popular medium. Much of the work of comics scholarship, especially the work of practitioner Scott McCloud, strives to break down this perceived distinction. Indeed, Will Eisner, one of the most important thinkers in comics scholarship, believed profoundly that comics—even the most mainstream and popular—are an art form and should be examined as such.

Broadly speaking, there are two major types of comics: mainstream comics and “literary” comics. Mainstream comics, usually sold by single issues released monthly called floppies and later collected into volumes called trade paperbacks, encompass comics genres like superhero comics (think Superman) and slice-of-life comics (think Archie). In Canada, these types of comics were last really commercially successful during the Second World War. What we think of as more literary comics—what you might be accustomed to calling graphic novels—are released in single volumes, and usually look and feel more like a traditional book; these are often referred to as alternative comics because they came about largely in opposition to the limited voices and perspectives of mainstream comics. Most Canadian comics since the 1970s have been of this sort, with Drawn & Quarterly the largest Canadian publisher.

Regardless of which type of comic you are looking at, the grammar of comics remains the same: a comics page is typically divided into panels; each panel has a border surrounding it; and the space between borders is called the gutter. Thierry Groensteen lays out what he calls the “system of comics” in his book of the same name, where he reflects not only on these key concepts but also on how the reader engages with the layout of the comic; as he and McCloud both discuss, comics are a highly participatory medium. Scholars look at not only the pictures and the text, but the layout of the comic, too, remembering that comics artists are often very particular about how they choose to structure their work in order to best shape the storytelling. For an example of how scholars attend to borders and gutters in the analysis of comics, see “Border Studies in the Gutter: Canadian Comics and Structural Borders” published in Canadian Literature 228-229 (2016).

Research on Canadian Comics Traditions

It can be useful to consider the distinction between mainstream and literary comics in relation to comics criticism as well.

Mainstream Superhero Comics

A fan’s representation of Captain Canuck. Shannon Hayward, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

A robust body of scholarship focuses on the mainstream comics mainstay of the nationalist superhero in Canadian comics and how it functions differently (and typically far less successfully) than in American comics. This is a fertile ground for research given the significance of the Second World War period to the history of Canadian comics, when nationalist adventure stories were in particular demand. Scholars study how in nationalist adventure stories, Canadian figures like Johnny Canuck as well as Captain Canuck and Nelvana of the Northern Lights have all had moments of commercial success, but these figures have not achieved the national commercial success like Captain America holds in the US. Captain Canuck is a good example of the tension between a desire to see Canadian heroes on comics pages, as evidenced by audience response research by Jason Dittmer and Soren Larsen that shows an appreciation for the existence of the comic and strong brand recognition for the character, and the paradoxically resounding failure of these comics commercially, as explored by Bart Beaty. Ryan Edwardson brings these seemingly contradictory arguments together to discuss the larger significance of the figure of Captain Canuck, more recognizable as an icon than for the comics he appears in themselves. As Edwardson notes, it is perhaps the idea of Captain Canuck, which offers “a sense of national identity in a cultural arena where New York overwhelms New Brunswick, and one rarely sees a maple leaf,” that leads readers to appreciate its existence in theory even when they do not support it financially (199).

Nationalist superheroes like Captain Canuck (and Johnny Canuck before him) often represent a very myopic vision of Canadian identity, being universally white, mostly Anglophone, explicitly Christian, and—with few exceptions such as Canada’s first female superhero, Nelvana of the Northern Lights—almost exclusively male. This myopia of English Canadian mainstream comics offerings for most of the twentieth century led to the rise of alternative superhero comics through the 1970s (such as Capitaine Kébec) and into the contemporary era (such as Bryan Lee O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim series, “a fusion of North American and Japanese comic book styles” [Hudson]).

Literary Comics’ Representations of Identity

Although literary comics have a shorter tradition historically, scholarship on these comics tends to dominate the contemporary research landscape likely because the comics are more closely akin to literature. Where scholars studying superhero comics tend to be interested in the comics as cultural objects, scholars of literary comics tend to critique them as a piece of art, just like a novel, film, or painting. In their articles in Canadian Literature, Marni L. Stanley and Katie Mullins engage queer and feminist theory, respectively, to challenge the dominance of cisgender male, heterosexual, white stories in Canadian comics. Likewise, as Jason Dittmer and Soren Larson show, Indigenous characters in Canadian comics have often been depicted stereotypically, a “conventional form of internal Orientalism in Canadian comics that recognizes indigeneity but denies its modernity” (66). As Dittmer and Larson explain, “Indigeneity is conflated with [the] North in this internal Orient: raw, strange, and unpredictable. The quality of ‘Canadian-ness’ is described as an ongoing encounter with, and ultimately possession of, this world” (65). It would be desirable to see more analyses based on feminist, queer, critical race theory, and Indigenous approaches to comics in Canada, given the problematic racist and sexist depictions rooted in both mainstream and alternative comics traditions.

The Toronto Comics Arts Festival, 2010. Dedicated to all things comics, TCAF has been yearly running since 2003. Erin Balser, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, via Flickr.

Research Questions to Consider

- How might scholarly approaches to Canadian literature and nationalism help to explain the fascination with (and lack of success of) the nationalist superhero figure? Search for scholars of Canadian nationalism who do not research comics, such as Northrop Frye and Frank Davey, and apply their arguments to a comic book or a set of strips featuring a Canadian superhero. (For context, see CanLit Guides resources on nationalism (late 1800s to 1950s; 1950s and 1970s; 1980s to this century; and “Nationalism, Now”).

- Using a scholar who studies comics and gender (such as Mullins), consider how recent comics in Canada address and/or respond to contemporary gender debates of popular culture rooted in online phenomena like Gamergate, Sad Puppies, #NotAllMen, #metoo etc. See the Robot Hugs comic “Risky Date,” which addresses online conversations about Rape Culture as an example.

- Choose a comic where the protagonist is not a cisgender, heterosexual, white male character and, drawing on a scholarly source such as Dittmer and Larsen or Stanley, conduct a close reading that explores the text as writing back to or writing against a larger comics tradition. If you wish to examine race, then draw upon scholarship by academics who study Canadian literature more broadly, such as Smaro Kamboureli or Larissa Lai.

Works Cited

- Beaty, Bart. “The Fighting Civil Servant: Making Sense of the Canadian Superhero.” American Review of Canadian Studies 36.3 (2006): 427-39. Print.

- Dittmer, Jason, and Soren Larsen. “Aboriginality and the Arctic North in Canadian Nationalist Superhero Comics, 1940-2004.” Historical Geography 38 (2010): 52-69. Print.

- —. “Captain Canuck, Audience Response, and the Project of Canadian Nationalism.” Social and Cultural Geography5 (2007): 735-53. Print.

- Edwardson, Ryan. “The Many Lives of Captain Canuck: Nationalism, Culture, and the Creation of a Canadian Superhero.” The Journal of Popular Culture2 (2003): 184-201. Print.

- Eisner, Will. Comics and Sequential Art. New York: WW Norton, 2008. Print.

- Gray, Brenna Clarke. “Border Studies in the Gutter: Canadian Comics and Structural Borders.” Canadian Literature 228-9 (2016): 170-87. Print.

- Groensteen, Thierry. The System of Comics. Trans. Bart Beaty and Nick Ngyuen. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2007. Print.

- Hudson, Laura. Bryan Lee O’Malley Talks ‘Monkey Manga’ with the Men Who Influenced ‘Scott Pilgrim’ [Exclusive]. 14 July 2011. Web. Accessed 28 Feb. 2018.

- McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperCollins, 1994. Print.

- Mullins, Katie. “Questioning Comics: Women and Autocritique in Seth’s It’s a Good Life, If You Don’t Weaken.” Canadian Literature 203 (2009): 11-27. Print.

- Stanley, Marni L. “Drawn Out: Identity Politics and the Queer Comics of Leanne Franson and Ariel Schrag.” Canadian Literature 205 (2010): 53-68. Print.

©

©