Researchers have long understood the importance of the periodical press to the cultural and political history of Canada. Its role in the history of women’s literary publishing has become an especially rich site of scholarly inquiry in recent decades. Increasing interest in book history, archival theory, and the digital humanities continues to open up fascinating questions about a text’s relationship to the material world that produces it, and about the periodical itself as a genre or mode of publication substantially different from monograph publishing.

Periodical Publishing and Women Writers of the Nineteenth Century

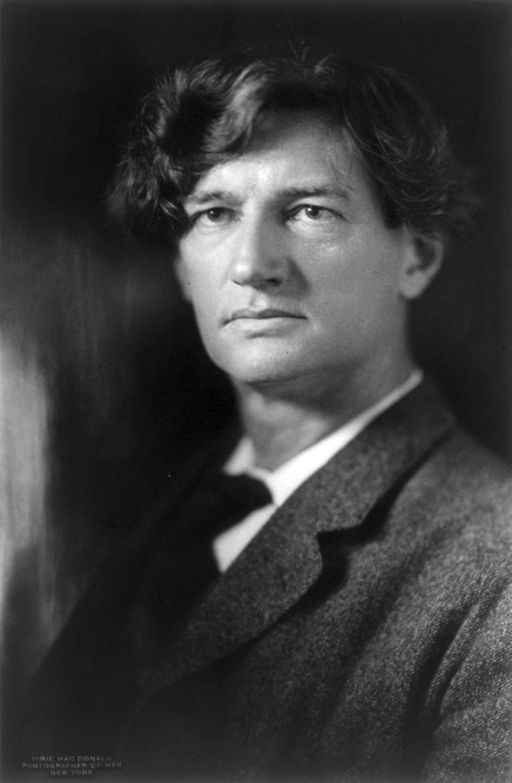

Mary Ann Shadd, founder of the Provincial Freeman, was the first Black woman editor and publisher in Canada. Library and Archives Canada (C-029977)

Early periodicals showcased the writing of women who played important roles in Canada’s literary history, including Susanna Moodie, Sui Sin Far (Edith Eaton), Mary Ann Shadd, Isabella Valancy Crawford, Sara Jeannette Duncan, E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake), Agnes Maule Machar (“Fidelis”), L. M. Montgomery, and many others. Newspapers and magazines were important publishing venues for women writers, for whom monograph publishing was especially difficult: periodical publishing was one area in which women could hope to achieve rates of pay comparable to those received by men, and, as Susan Coultrap-McQuin shows, women writers were often able to build working relationships with editors, allowing greater access to audiences. For their part, editors became eager to publish work written by women because women were making up an increasingly substantial part of their readership. Intense competition between publications, especially newspapers, in the late decades of the nineteenth century set editors clamouring for material of particular interest to women, thereby opening new opportunities for women’s creative and journalistic writing. Janice Fiamengo’s analysis in The Woman’s Page: Journalism and Rhetoric in Early Canada explores the rhetorical strategies women writers used to exploit these opportunities and insert themselves into public debate, and is one example of the kinds of scholarship being done in this area.

Periodical Publishing and Recovering Literary History

The abundance of writing by professional and amateur women in the archives of nineteenth-century newspapers and magazines shows the significance of the periodical press to the history of women’s writing in this country. If we include the periodical press in our understanding of literary history broadly, we can access other ways of looking at that history, ways that even challenge how we define Canadian literature. Mary Ann Shadd, for example, an active contributor to periodicals in the 1850s and the first Black woman to start a newspaper in Canada (the Provincial Freeman and Daily Advertiser) was born in the US, lived in Canada for a time, and wrote about abolition and suffrage for publications on both sides of the border. In her essay “Writers Without Borders,” literary scholar Carole Gerson explains that “Canadian writers, particularly those working in English, have always operated in an international context with regard to the content of their texts, the location of their publishers, their desire for an audience, and their own travels and domiciles” (16). Indeed, many of the nineteenth-century writers we claim as belonging to a particularly Canadian tradition in fact participated in a much broader literary culture that extended beyond national boundaries.

Edith Eaton, also known as Sui Sin Far, was the first published Chinese Canadian writer. Reproduced from the Canada’s Early Women Writers collection. SFU Library Digital Collections. Simon Fraser University. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

As Nick Mount shows, Bliss Carman is another good example of an author who, like Shadd, complicates our understanding of a national literature. Despite his important place in the Canadian literary canon, despite even his status as Canada’s first poet laureate, Carman spent his career living in the US, publishing in American periodicals for an American audience that widely saw him as an American poet. His career and the careers of many of his contemporaries allow us to see the ways periodical publications moved through and across boundaries of various kinds.

Periodical Publishing and Questions of Genre and Archival Theory

Whether they are studying individual early authors, such as Carman, or particular early publications, scholars working in the literary archives inevitably encounter questions related to the recovery of early texts: What do we do with these texts once we’ve “found” them? How can we incorporate them into what we already understand about an author or a time period? How do we decide what is worth preserving? What kinds of opportunities and challenges do shifting technologies offer archives and archivists? Some cultural historians and literary scholars such as Linda Morra and Jessica Schagerl have begun to grapple with these and other questions, particularly as they relate to methodologies of archival research and the interpretation of archival material.

Scholars must also encounter basic questions about the status of the periodical as a genre. As critics who work with periodicals readily acknowledge, the genre has been undervalued and under-studied despite its longstanding influence through centuries of cultural history. Margaret Beetham suggests that, in part, this is because of the difficulty of defining the text when it comes to a literary work published in a periodical. History often stabilizes what is characteristically un-stable about the periodical as a form: periodical fiction is turned into novels; poetry is collected into volumes. The work of poet E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake), who was of Mohawk and British descent, is a case in point: we might read her poem “Cry From an Indian Wife” either in the 1895 collection White Wampum, or in a contemporary anthology of Canadian or Indigenous literature, but not on its own in the magazine The Week where it was first published in 1885. In its original context, in the wake of the Métis uprisings in the west, Johnson’s poem condemning the government’s appropriation of Indigenous land would have stood in stark contrast to the generally pro-government sentiment that was being published at the time in English Canadian newsprint. If we remove this context, what gets lost? Is Beetham accurate in suggesting that changing the mode of publication significantly changes a text the same way translation would?

Research Questions to Consider

Library and Archives Canada on Wellington Street in Ottawa, Ontario. Photograph by Padraic Ryan, via Wikimedia Commons.

- Carole Gerson and other scholars have identified an explicitly nationalist agenda in the shaping of the Canadian literary canon, a process that has historically excluded women writers and racialized writers, and devalued periodical publishing (see “‘The Most Canadian of all Poets’: Pauline Johnson and the Construction of a National Literature”). If the literary canon is that collection of texts deemed by the majority of scholars and readers to be important or representative of a particular tradition, how can archival research productively engage with or even disrupt questions of canon formation? In what ways does the archive challenge established historical narratives?

- In what ways do the political or social aims of a periodical—or indeed of its editor or curator—inform it as a piece of literature? How can you find out what those aims are? Does it matter if they are implicit or explicit?

- What is the relationship between a text and what surrounds it on the page? How does the format of a literary text change our experience of that text?

- Compare the approach to nineteenth century literature by Mary Lu MacDonald in her 1991 article, “‘A Very Laudable Effort’: Standards of Literary Excellence in Early Nineteenth Century Canada” with that of Carole Gerson in her 2009 article, “Writers Without Borders: The Global Framework of Canada’s Early Literary History.” How has the critical/scholarly discussion changed?

Works Cited

- Beetham, Margaret. “Towards a Theory of the Periodical as a Publishing Genre.” Investigating Victorian Journalism. Ed. Laurel Brake, Aled Jones, and Lionel Madden. Houndmills: Macmillan, 1990. 19-32. Print.

- Coultrap-McQuin, Susan. Doing Literary Business: American Women Writers in the Nineteenth Century. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 1990. Print.

- Fiamengo, Janice. The Woman’s Page: Journalism and Rhetoric in Early Canada. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2008. Print.

- Gerson, Carole. “‘The Most Canadian of all Poets’: Pauline Johnson and the Construction of a National Literature.” Canadian Literature 158 (1998): 90-107. Print.

- —. “Writers Without Borders: The Global Framework of Canada’s Early Literary History.” Canadian Literature 201 (2009): 15-34. Print.

- MacDonald, Mary Lu. “’A Very Laudable Effort’: Standards of Literary Excellence in Early Nineteenth Century Canada.” Canadian Literature 131 (1991): 84-99. Print.

- Morra, Linda, and Jessica Schagerl, eds. Basements and Attics, Closets and Cyberspace: Explorations in Canadian Women’s Archives. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2012. Print.

- Mount, Nick. When Canadian Literature Moved to New York. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2006. Print.

©

©