Poetry takes many forms, ranging from quite rigid ones like the ever-popular sonnet (see the books on poetic forms by Skelton and by Braid and Shreve below) through to a diversity of less formally rigorous approaches.

Up until relatively recently, poetry often required more stylized and figurative language in particular forms. Poetic forms began to shift in the early 1800s with William Wordsworth and the Romantics. In the preface to Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth describes his principle objective

as to make the incidents of common life interesting

(235) and to speak a plainer and more emphatic language

(236).

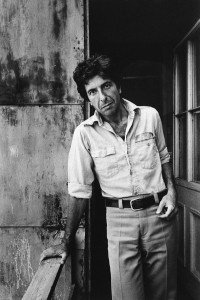

Leonard Cohen was a part of the later Modernist emphasis on free-verse poems that wove sensuality with mythology. His 1961 book The Spice-Box of the Earth earned him widespread praise. Leonard Cohen. Sam Tata, Library and Archives Canada, accession number 1975-150 NPC, RD-001290.

Modernism continued to rebel against formalism by popularizing free verse poetry. Since then, some poets work to question all the norms and conventions of both everyday language and of earlier poetry, while others continue to explore the creativity within these various poetic forms (e.g. see Braid and Shreve’s examples).

The poems discussed throughout CanLit Guides range across a spectrum of approaches, from free-verse lyric poetry to more experimental forms.

Lyric, meaning song-like, comes from the lyre that the Greek and Roman bards used to accompany their oral performances. But even this convention—that poetry should sound rhythmic and harmonious—has been violated by poets, who have moved to other ways to distinguish their words as poetry.

For example, Gertrude Stein’s A rose is a rose is a rose

could be said to rhyme, and to use poetic imagery, but it’s a flat, almost philosophical statement, as well.

The examples that follow do not necessarily fit into hard, poetic categories, but illustrate different styles of expression and the challenges they pose to readers.

Also, different approaches suggest important features of poetic practice and interest. For instance, traditional lyrical approaches, such as those of the Romantics, are often interested in narrative and description, whereas experimental poetry may be more interested in processes of meaning production and formal manipulations that inform these narratives and representations.

Using Space on a Page

There are many possibilities for innovative uses of page space. Lines and stanzas are the most common way to group words on a page, but they can be arranged in a variety of ways. Concrete poets have even moved to play with letters on the page as if they were visual artists.

What is important to remember is that these spatial or formal strategies often contribute to the meaning of the poem, and should be considered in relation to the words themselves.

Reference Works

If you want to study poetic forms further, or to experiment with writing poetry in different forms, you might find the following books useful:

- Kate Braid and Sandy Shreve’s In Fine Form: The Canadian Book of Form Poetry (2005).

- Robin Skelton’s Shapes of Our Singing: A Comprehensive Guide to Verse Forms and Metres from Around the World (2002).

Works Cited

- Braid, Kate, and Sandy Shreve, eds. In Fine Form: The Canadian Book of Form Poetry. Vancouver: Polestar, 2005. Print.

- Skelton, Robin. Shapes of Our Singing: A Comprehensive Guide to Verse Forms and Metres from Around the World. Seattle: U of Washington P, 2002. Print.

- Stein, Gertrude. Geography and Plays. Boston: Four Seas, 1922. Print.

- Wordsworth, William, and Samuel Coleridge. Lyrical Ballads. Ed. R.L. Brett and A.R. Jones. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 1991. Print.

©

©