E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake) was a contemporary of D. C. Scott. Indeed, Scott was on the same program in Toronto that began Johnson’s performing career in 1892 (Gray 140). Johnson even dined at his home once, although Mrs. Scott did not agree to let her wear her buckskins (Gray 147). The daughter of a Mohawk chief and an Englishwoman, Johnson is remembered for publicly embracing her Mohawk heritage in her poetry and her public performances.

In her 1892 piece “A Strong Race Opinion,” Johnson wrote against racializing stereotypes, particularly of Indigenous women. As she notes, Indigenous women in nineteenth-century fiction are depicted as the same stock character—many even sharing the same name, Winona—and share a similar narrative of a doomed romance with a white man, followed by suicide. Johnson argues that this “regulation Indian maiden” (178) is a construction based on stereotypical assumptions about Indigenous people and not on authentic contact and knowledge, and she calls for more considered and well-rounded portrayals in fiction:

The story-writer who can create a new kind of Indian girl, or better still portray a ‘real live’ Indian girl who will do something in Canadian literature that has never been done, but once. The general author gives the impression that he has concocted the plot, created his characters, arranged his action, and at the last moment has been seized with the idea that the regulation Indian maiden will make a harmonious background whereon to paint his pen picture, that, he, never having met this interesting individual, stretches forth his hand to his library shelves, grasps the first Canadian novelist he sees, reads up his subject, and duplicates it in his own work. (2)

Despite Johnson’s tendency to revert to essentialism in her critique of racialization, she was ahead of her time in calling attention to these issues. Johnson’s empathetic approach is in contrast with Scott’s paternalistic speaking for Indigenous peoples.

In contrast to Scott’s subjugating gaze, Johnson sought to foster intercultural empathy and understanding through her poetry and performances. As Carole Gerson notes, Johnson’s reputation appears to have been in part a victim of a masculine bias and nationalist agenda in academic high modernism, which privileged detachment and formalism over “emotion, domesticity, community and popularity” (91–92). The very sentimentality that led modernist critics to reject Johnson’s work as too emotional is one of the things that critics now find so engaging about her poetics. Johnson uses affect in her poetry to build bridges between peoples.

Johnson was vocal about the totalizing racialization of the “Indian” in European Canadian and American literature:

The Indian girl we meet in cold type … is rarely distressed by having to belong to any tribe, or to reflect any tribal characteristics. She is merely a wholesale sort of admixture of any band existing between the Mic Macs of Gaspé and the Kwaw-Kewlths of British Columbia, yet strange to say, that notwithstanding the numerous tribes, with their aggregate numbers reaching more than 122,000 souls in Canada alone, our Canadian authors can cull from this huge revenue of character, but one Indian girl, and stranger still that this lovely little heroine never had a prototype in breathing flesh-and-blood existence! (“A Strong Race Opinion” 1–2)

Johnson is encouraging poets and writers to replace racialization with particularity. Rather than having one woman as a prototype for all Indigenous women, Johnson is imploring writers to deal with “flesh-and-blood” women, women who belong to particular tribes, and who have particular tribal characteristics. Most importantly, she is imploring writers to move away from only discussing native women in terms of their tragic, unrequited love for powerful white men. Johnson’s desire for the representation of particularity is in stark contrast to Scott’s using “The Onondaga Madonna” as a stand-in for all Indigenous women. His Madonna is a tragic figure who is a kind of essentialized Indigenous everywoman.

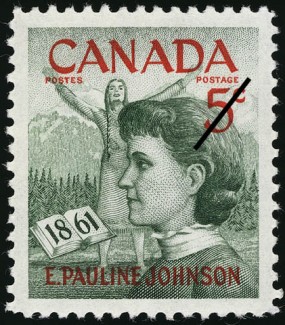

Commemorative stamp of E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake), issued in 1961. Canada Post Corporation, Library and Archives Canada: POS-000442.

In her reflection on Veronica Strong-Boag and Carole Gerson’s scholarly biography of Johnson, Paddling Her Own Canoe, Janice Fiamengo notes that Johnson’s straddling of Mohawk and white English culture seems to have produced multiple, conflicting positions. Johnson negotiated her position in Canada as a Mohawk woman “attempt, against powerful odds, to imagine a new Canadian nationality based on mutual partnership between Whites and Indigenous peoples” (Fiamengo 175). Between 1892 and 1909, Johnson gave over 2000 public performances where she recited her own work. Usually in these performances she wore an Indian costume of her own design in one half, and Victorian evening dress in the other. Some see her as sensationalizing her mixed heritage and materializing the division between her Mohawk and English ancestry. Others argued that she used her Indian costume to appeal to crowds accustomed to Wild West shows, and the evening dress to make clear that she was also as good a poet and as much a lady as any other Canadian woman.

Works Cited

- Fiamengo, Janice.

Reconsidering Pauline.

Canadian Literature 167 (2000): 174–76. Print. - Gerson, Carole.

Canadian Literature 158 (1998): 90–107. Print. (PDF)The Most Canadian of all Canadian Poets

: Pauline Johnson and the Construction of a National Literature. - Gray, Charlotte. Flint & Feather: The Life and Times of E. Pauline Johnson. Toronto: HarperFlamingo, 2002. Print.

- Johnson, E. Pauline.

A Strong Race Opinion: On the Indian Girl in Modern Fiction.

1892. CanLit Guides. U of British Columbia (Canadian Literature), Apr. 2013. Web. 5 Apr. 2013. (PDF)

©

©