In many ways, feminism is a movement about making revolutionary changes to our culture and power relations between men and women. One central concern of second-wave feminism was expanding the status of women beyond their prescribed roles as mothers and wives. However, conservative feminism has a more essentialist take on gender that seeks to re-establish the value of these traditional roles of women as wives and mothers. One of the reasons why postfeminism is associated with conservative feminists is that both movements argue that feminism, as a revolutionary engine of change, is over. For conservative feminists, instead of continuing to engage in feminist struggles, women should return to the home, while having the chance to do it all, and can turn their attention to preserving the gains made for the status of women in the West and improving gender relations in other parts of the world.

For example, conservative feminist Christina Hoff Sommers, author of The War Against Boys (2000) and Who Stole Feminism (1994), argues that feminism is essentially over in America, since “the major battles of women for equality and opportunity have been fought and won” (Freedom Feminism 4–5). For Sommers, feminism and feminists should now turn their attention away from America to the places in the world where “the quest for equality has hardly begun” (5). Frequently, this kind of feminism comes with an interventionist bent. One of the ways that the war in Afghanistan was justified was by arguing that such a war would improve the status of women in Afghanistan. This is not to imply that all conservative feminists are confortable with embracing the label of feminism.

In The Flipside of Feminism, conservative feminist Suzanne Venker and Phyllis Schlafly argue that feminism is fundamentally progressive, and that conservative working mothers are the most liberated women in America. For Schlafly and Venker, rather than trying to find a place for conservative women within feminism, women who care about gender should embrace traditional gender values.

Figure of “A Model of Elegence and Hygiene” from L’éducation Physique féminine (1921) by Georges HébertPublic domain, Wikimedia Commons

Conservative feminists aggressively embrace femininity and the beauty myth as a way of pushing back against against the critique of femininity and female beauty in second-wave feminism. Second-wave feminist were critical of femininity, and as Joanne Hollows, the rejection of femininity was essential to the second wave of feminism: “femininity was constituted as a ‘problem’ in second-wave feminism. For many feminists, feminine values and behaviors were seen as major causes of women’s oppression” (2). According to feminist cultural theorist Naomi Wolf in The Beauty Myth, freedom for women is beset with an obligation to be beautiful, and this obligation is a new means of social and ideological control over women’s bodies. For Wolf, the beauty myth

has grown stronger to take over the work of social coercion that myths about motherhood, domesticity, chastity, and passivity, no longer can manage. (11)

Many conservative feminists thinkers and activists react against feminists such as Wolf, and make a point of dressing as femininely as possible and make a virtue of their homes, husbands, and maternity.

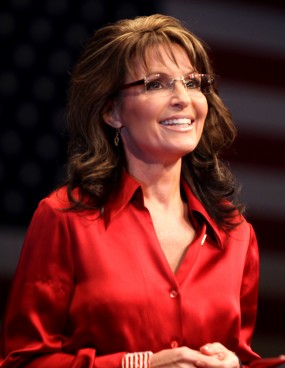

Sarah Palin

Perhaps the poster woman for the conservative feminist movement is former US Republican Vice Presidential candidate Sarah Palin. For example, during her infamous interview with Katie Couric of CBS News, Palin said that she is “a feminist who believes in equal rights,” and “that women certainly today have every opportunity that a man has to succeed and to try to do it all anyway” (Pelikan n. pag.). Palin’s labelling of herself as a feminist set off a media firestorm, especially because “feminist” is a label that conservative female politicians have traditionally avoided.

Palin’s insistence that women have the right to try to “do it all” has a long and potentially sexist history. The implicature of Palin’s comment is that women have the right to try to balance having a family and a job, but also that the end result of feminism is getting women to a place where they have the right to both work and raise a family. There is a casual sexism underlying Palin’s comments—“having it all” by balancing work and home is traditionally a concept associated with women, not men. It is simply expected that men can work, have a family, and have children. But for conservative feminists, women seem only to have the right to have a job if they can balance their implicitly primary obligation of taking care of their family with their secondary obligation of working outside the home. The end result of feminism, for Palin, is the creation of working mothers who work and live for others, not the disestablishment of patriarchy.

In her later activism during the 2012 American presidential campaign, Palin said that the Republican Party would see a rise of women’s voters in the form of “pink elephants” and “mama grizzlies.” She says in her Mama Grizzlies campaign video that there is a “mom awakening” among conservative women, an awakening that she describes through the metaphor of a mama grizzly. According to Palin, “Moms kinda just know when something’s wrong.” Palin imagines the mama grizzly on her back legs, alert, sensing danger to her cubs. Such women are metaphorically configured as nurturing but protective and primal animals trying to protect their children from “fundamental changes” (Mama Grizzlies) that liberals are making to America—changes that Palin implies must be resisted for the good of the family.

Much of the negative reaction to Palin came from women on the left who thought that Palin simply could not in good faith call herself a feminist. Feminist writer Jessica Valenti, author of The Purity Myth (2009), wrote an opinion piece for the Washington Post arguing that Palin “isn’t a feminist” and that Palin “deliberately misrepresent[s] real feminism to distract from the fact that she supports policies that limit women’s rights” (n. pag., emphasis added). Valenti’s argument that Palin is not a real feminist demonstrates the philosophical gulf between different poles of feminism. Also responding to Palin’s video, Los Angeles Times columnist Meghan Daum, while calling Palin’s logic regarding policy “contorted,” defends Palin’s right to call herself a feminist: “I feel a duty (a feminist duty, in fact) to say this about Palin’s declaration: If she has the guts to call herself a feminist, then she’s entitled to be accepted as one” (n. pag.). The controversy over Palin and conservative feminism reflects the difficulty of reconciling conflicting interests within the feminist movement.

Works Cited

- Wolf, Naomi. The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women. 1991. New York: Perennial, 2001. Print.

- Venker, Suzanne, and Phyllis Schlafly. The Flipside of Feminism: What Conservative Women Know-and Men Can’t Say. Washington: WND, 2011. Print.

- Valenti, Jessica. “The Fake Feminism of Sarah Palin.” Opinion. Washington Post. 30 May 2010. Web. 10 Sept. 2013. (Link)

- Hollows, Joanne. Feminism, Femininity and Popular Culture. New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Print.

- Daum, Meghan. “Sarah Palin, feminist.” Editorial. Los Angeles Times. 20 May 2010. Web. 10 Sept. 2013. (Link)

- Sommers, Christina Hoff. Freedom Feminism: Its Surprising History and Why It Matters Today. Lanham: AEI, 2013. Print.

- SarahPalinAK. Mama Grizzlies. YouTube, 23 June 2010. Web. 10 Oct. 2013.(Link)

©

©