Montreal nightlife. Favourite roadhouse for men-about-town clientele is Ruby Foo’s, which specializes in Chinese food, 1951. Reproduced with permission from Library and Archives Canada (Weekend Magazine collection/e005477035).

Lily Cho’s Eating Chinese: Culture on the Menu in Small Town Canada (2010) provides the first in-depth study of the small-town Chinese restaurant as source of “cultural production” (of creative works, texts, images, and artifacts) and one way to think about the experience of immigration and acculturation. You can read Guy Beauregard’s review of Cho’s book in Canadian Literature 219 (2013). Cho focuses her analysis on the restaurants themselves, on those who own and work in them, on the food they serve, and on the menus they construct to represent changing cultural and national identities. She sees rural restaurants as contained yet open sites where Chinese immigrants negotiated otherness and shifting power relations within the dominant culture. Cho argues that restaurants historically offered “a vision of what ‘Canadian’ and ‘Chinese’ meant through the text of the restaurant menu,” which typically offered “western” fare (51), and where Chinese food items were “not differentiated by regional categories such as Szechuan or Hunan, but by genres such as ‘egg foo yong’” (7).

Cho devotes an entire chapter to the poetry of Fred Wah, with an emphasis on Diamond Grill. In part, this is because Wah’s “biotext”—a collection of autobiographical prose and poetry by an author of mixed-race Chinese heritage about his family and the various Chinese restaurants in which they worked—is a sophisticated reflection on some of the same issues that preoccupy Cho. Wah’s and Cho’s books both pose two central questions: “how does a diasporic community,” or community of immigrants from a wide variety of places, “understand itself as such?” (Cho 131); and what is the relationship of the immigrant or “diasporic subject” to China and “Chineseness” (Cho 139)?

While Cho examines the small-town Chinese restaurant, other critics include urban examples when exploring representations of the Chinese Canadian community in a restaurant context. In “Asian North America in Transit” (1999), literary critic Glenn Deer discusses “immigrant mobility” and his father’s Edmonton restaurant. As with Cho, the Chinese restaurant is a lens through which Deer explores the immigrant and diasporic experience. In “Chop Suey Writing: Sui Sin Far, Wayson Choy, and Judy Fong Bates,” Maria N. Ng takes issue with restaurant narratives as being “forever chained” to spaces and stereotypes that are not reflective of twenty-first-century immigrant experiences (171). When exploring Chinese restaurant literature, you may want to concentrate on representations of the restaurants themselves, what prompts them, and what characteristics these works share with respect to those themes we raised earlier of visibility, mobility, and communication. Although some of the earlier restaurant literature emphasizes barriers that are hard to overcome, more recent texts—you can think here especially of the recipe sharing in Wah’s Diamond Grill and in Janice Wong’s culinary memoir Chow: From China to Canada: Memories of Food + Family—increasingly reflect and expand a range of cultural literacies. In the context of this chapter, cultural literacy refers to an individual’s increasing fluency in the language and idioms, as well as the foundational norms, values, and stories of another culture. Wah’s and Wong’s books both invite readers to heighten their understanding of the complexities of Chinese culture in Canada, while at the same time glimpsing the way characters within these texts are enriching their own cultural literacy as they move between countries, and between Canadian towns and cities. In this regard, Chinese restaurant literature becomes part of the larger cultural life of restaurants— those “resilient” institutions that Adam Gopnik describes as “places of hope . . . reminding us of lives and appetites beyond our own” (52).

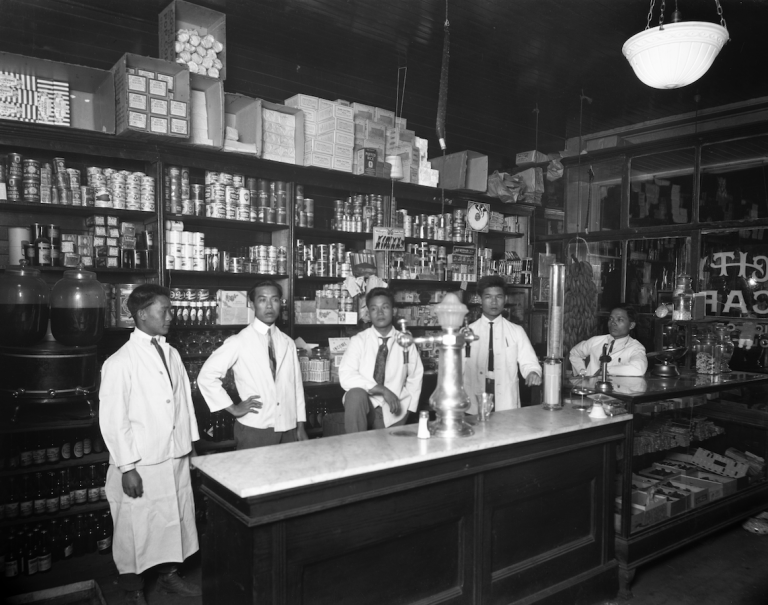

Interior of City Cafe and Chinese restaurant in Lacombe, Alberta [ca. 1900-1935]. Photograph by B. S. Cameron. Reproduced with permission from the Glenbow Archives (ND-2-109).

Research Questions to Consider

- Create a working definition of the term “diaspora” based on scholarship that takes up the subject. What are some of Canada’s different “diasporic communities”? How do representations of food and restaurants in literature contribute to/complicate/contest the ways in which we understand diasporic community formation? Here are a couple of texts that can help you to formulate your answer: Lily Cho’s article “Asian Canadian Futures: Diasporic Passages and the Routes of Indenture” in the special issue on Asian Canadian Studies in Canadian Literature 199 (2008) and Maria Noëlle Ng’s “Mapping the Diasporic Self” (2008).

- In Diamond Grill, Fred Wah describes what he calls his hybrid identity, and his complex relationship to Chineseness as a Canadian-born child of mixed-race heritage. What is a hybrid identity? Create a list of five components of a hybrid identity and cite evidence from Diamond Grill to support your claims. Then read Guy Beauregard’s “Rattling a Noisy Hyphen” (1998), which is a review of Wah’s text, and compare your conclusions.

- In what way might Canada’s legacy of racism affect what stories were shared by the Chinese community throughout the twentieth century, and how they were told? Read Guy Beauregard’s “Re: Composing Biotexts” (2007) and examine how Fred Wah’s mode of life-writing in Diamond Grill enables him to explore his familial history in relation to Canada’s history of racist legislation.

Works Cited

- Beauregard Guy, “Rattling a Noisy Hyphen.” Rev. of Diamond Grill, by Fred Wah. Canadian Literature 156 (1998): 171-72. (PDF)

- —. “Re: Composing Biotexts.” Rev. of Writing the Roaming Subject: The Biotext in Canadian Literature, by Joanne Saul, and Diamond Grill, by Fred Wah. Canadian Literature 194 (2007): 175-77. (PDF)

- —. “Remapping Chineseness.” Rev. of Miah, by Julia Lin, Eating Chinese: Culture on the Menu in Small Town Canada, by Lily Cho, and Chinese Blue, by Weyman Chan. Canadian Literature 219 (2013): 145-47. (Text)

- Cho, Lily. “Asian Canadian Futures: Diasporic Passages and the Routes of Indenture.” Canadian Literature 199 (2008): 181-201. (PDF)

- —. Eating Chinese: Culture on the Menu in Small Town Canada. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2010. Print.

- Deer, Glenn. “Asian North America in Transit.” Editorial. Canadian Literature 163 (1999): 5-15. (Text)

- Gopnik, Adam. The Table Comes First: Family, France, and the Meaning of Food. New York: Knopf, 2011. Print.

- Ng, Maria N. “Chop Suey Writing: Sui Sin Far, Wayson Choy, and Judy Fong Bates.” Essays on Canadian Writing 65 (1998): 171-86. Web. 27 Apr. 2016.

- Ng, Maria Noëlle. “Mapping the Diasporic Self.” Canadian Literature 196 (2008): 36-45. (PDF)

- Wah, Fred. Diamond Grill. Edmonton: NeWest, 1996. Print.

- Wong, Janice. Chow: From China to Canada: Memories of Food + Family. North Vancouver: Whitecap, 2005. Print.

©

©