It’s important to remember that when multiculturalism first became policy, the public face of Canadian literature was still overwhelmingly dominated by the white, Anglo majority. The decades in which the Writing and Publications Program (WPP) operated between 1977-1998 were a period of significant change in the cultural and racial politics of both Canada and Canadian literature—a period when the nation’s literature and literary institutions began, belatedly, to reflect the historical and increasing diversity of Canadian society (Padolsky 361). As you read this section, though, it’s just as important to keep in mind that multiculturalism policy and the WPP alone did not create these changes. As writer/scholar/activist Larissa Lai reminds us, for many racialized and ethnic minority cultural workers, the 1980s-1990s period was transformative not because of multiculturalism itself, “but because community-based artists’, writers’, and activists’ responses to its limitations added to an organic energy that was already there in racialized Canadian communities” (ix). We will look at the WPP here as one “top-down” context in a wider paradigm of institutional change, before turning to explore how scholars have understood its effects and limitations.

Goals and Principles

As former multiculturalism program officer Judy Young explains, the objective of the WPP was to foster appreciation for multiculturalism by supporting the publication of “ethnic specific writing” that reflected Canada’s pluralism. It sought to achieve this in two ways:

- “To encourage the writing and publishing efforts of writers who use the non-official languages for their creative work as well as those writers who use the official languages but who have a specific cultural experience to convey”; and

- “To encourage the Canadian literary establishment and the reading public in general to view this literature as an aspect of Canadian literature.” (qtd. in Young 97)

These two goals seem complementary: the program would support culturally diverse writing, and in turn encourage Canadians to recognize the cultural diversity of Canadian literature. But, looking more closely, notice how they might also be contradictory. On the one hand, the WPP funded multicultural literature based on its difference from what was usually considered Canadian—writing in a “non-official” language, or in an “official” language but conveying a distinctive (“specific”) cultural experience. On the other hand, it wanted the “literary establishment” and general public to consider such writing as Canadian. In other words, the WPP made a distinction between ethnic minority and Canadian literature in what it funded, but also hoped to deconstruct this distinction itself. Judy Young describes this “ethnic/mainstream” binary as a “conundrum” (100)—one that we will keep in mind while we reflect on the program’s impact.

Grants and Texts

The WPP awarded grants of up to $5,000 to authors and $7,500 for publishers to support the production of literary texts, translations, educational materials, and events like public readings and literary conferences. The multiculturalism directorate’s budget for arts funding was never very large, particularly relative to the Canada Council. For example, during the 1980s, multiculturalism’s annual budget for arts programming was roughly $2 to $3 million, less than half of which went to literary writing and publishing grants; by comparison, the Canada Council’s annual grants budget during that same period grew from $44 million in 1980 to $95 million in 1990.

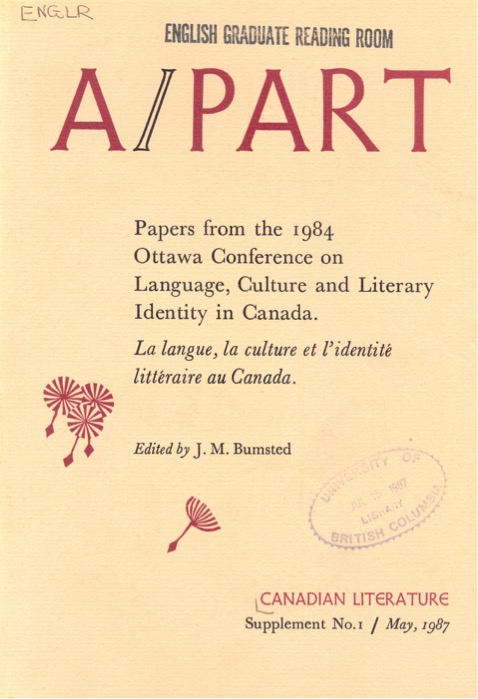

Nevertheless, the multiculturalism directorate made a substantial number of grants through the WPP—over 1,600 in total. A scan of the Literary Publications Supported by Multiculturalism Canada shows that many authors who are now prominent figures in Canadian literature—Himani Bannerji, Dionne Brand, George Elliott Clarke, Cyril Dabydeen, SKY Lee, Rohinton Mistry, Nino Ricci, and M. G. Vassanji, among many others—received support from the WPP, particularly in the early years of their careers. Grants also supported new anthologies of ethnic minority literature, such as Other Solitudes: Canadian Multicultural Fictions (1990), edited by Linda Hutcheon and Marion Richmond, the first “multicultural” anthology to have a wide impact on the Canadian literary field. Funds supported publications that contributed to early discussions of ethnicity and race in Canadian literary scholarship as well, like the special journal issue of Canadian Ethnic Studies on “Ethnicity and Canadian Literature” (1982). With WPP support, the journal Canadian Literature published A/Part: Papers from the 1984 Ottawa Conference on Language, Culture, and Literary Identity (1987), a special issue that collected research from one of the first major Canadian literature conferences focused on multiculturalism and minority writing, along with several other special issues on ethnic writing in the 1980s-1990s. Judy Young considers the publication of A/Part a “watershed” moment in the WPP’s efforts to “infuse some ‘ethnicity’ into ‘mainstream’” literary institutions (99)—in this case, the prominent academic journal Canadian Literature.

Masthead of A/Part acknowledging funding from Multiculturalism Canada. Canadian Literature Supplement No.1, 1987.

Amalgamation and Conclusion

In 1990, after the Multiculturalism Act (1988), the WPP and other performing and visual arts funding programs were amalgamated into a single Creative and Cultural Expression (CCE) program. The CCE continued to provide a parallel stream of writing and publishing grants, but now placed greater emphasis on promoting multiculturalism within dominant arts institutions such as federal and provincial arts councils. In the early 1990s, the Canada Council began making significant changes to its internal equity policies—in part because multiculturalism was now law, but largely in response to the extensive activism of racialized writers and cultural workers. It established a Racial Equity advisory committee and took steps to address the marginalization of minority writers within its hiring and granting practices. In the late 1990s, the government began deprioritizing arts funding in its multiculturalism programs, and after a 1997 strategic review it closed the CCE, effectively ending official multiculturalism’s dedicated funding for literature.

Reflection Questions

- Multicultural/Mainstream. The WPP funded “ethnic” literature based on its difference from the “mainstream,” but also hoped Canadians would view multicultural literature as part of Canadian literature. What do you make of this binary of ethnic and Canadian today? Is it still a “conundrum,” as Young described it? Has multiculturalism become a part of the mainstream of Canadian literature?

-

Cover of Canadian Literature 142/143. In the 1980s and 1990s, Canadian Literature received multiculturalism funding for a number of special issues in its “Connections” series on Canadian ethnic literatures, which included Caribbean (95, 1982), Italian-Canadian (106, 1985), Slavic and European (120, 1989), South Asian (142, 1992), East Asian-Canadian (140, 1994), and—as seen here—Hispanic-Canadian (142/143, 1994) writing. Canadian Literature, 1994.

Funding and Literature. Austin Cooke, a former multiculturalism program officer, argues that the WPP’s support for Canadian literature was one of official multiculturalism’s “most effective” activities: “over [a] twenty-year period,” states Cooke, “approximately 1,600 grants to writers, publishers, and writers’ groups helped implement the [multiculturalism] policy in this important area of Canadian life” (Stone et. al. 44). Yet many authors who earned WPP grants have been critical of official multiculturalism’s limitations, and may contest the notion that their writing be seen as evidence of the policy’s success. Is it problematic to claim that writers “implement” national multiculturalism just because they received funding from its programs? Does the political economy of a text’s production necessarily shape its cultural or literary value?

- Multilingualism. Have you encountered any Canadian literature in “non-official” languages, or published in translation? Canada’s model of multiculturalism within a bilingual framework—officially multicultural, but also officially bilingual—is paradoxical; it implies that language can be dissociated from culture. Is Canadian literature multicultural if it is only studied and taught in English or French?

Works Cited

- A/Part: Papers from the 1984 Ottawa Conference on Language, Culture and Literary Identity in Canada. Ed. J. M. Bumstead. Canadian Literature, Supplement No. 1, May, 1987. Print.

- Canada. Multiculturalism Directorate. Literary Publications Supported by Multiculturalism Canada. Ottawa: Supply and Services, 1984. Print.

- Hutcheon, Linda, and Marion Richmond, eds. Other Solitudes: Canadian Multicultural Fictions. Toronto: Oxford UP, 1990. Print.

- Kroetsch, Robert, Tamara Palmer, and Beverly Rasporich, eds. Ethnicity and Canadian Literature. Spec. issue of Canadian Ethnic Studies 14.1 (1982). Print.

- Lai, Larissa. Slanting I, Imagining We: Asian Canadian Literary Production in the 1980s and 1990s. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2016. Print.

- Padolsky, Enoch. “Canadian Ethnic Minority Literature in English.” Ethnicity and Culture in Canada: The Research Landscape. Ed. J.W. Berry and J.A. Laponce. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1994. 361-86. Print.

- Stone, Marjorie, Diana Brydon, Austin Cooke, Winfried Siemerling, and Christl Verduyn. “Literary Studies and the Metropolis Project: Bridging the Gaps.” Newsletter, Association of Canadian College and University Teachers of English (June 2002): 33-47. Print.

- Young, Judy. “No Longer ‘Apart’: Multiculturalism Policy and Canadian Literature.” Canadian Ethnic Studies 33.2 (2001): 88-116. Print.

©

©