What is Border Studies?

The city of Nogales is divided in two by the Mexico-US border. This photograph shows the Mexican side, commemorating those who have died trying to cross into the United States. Jonathan McIntosh, “Wall of Crosses in Nogales,” 2009. CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

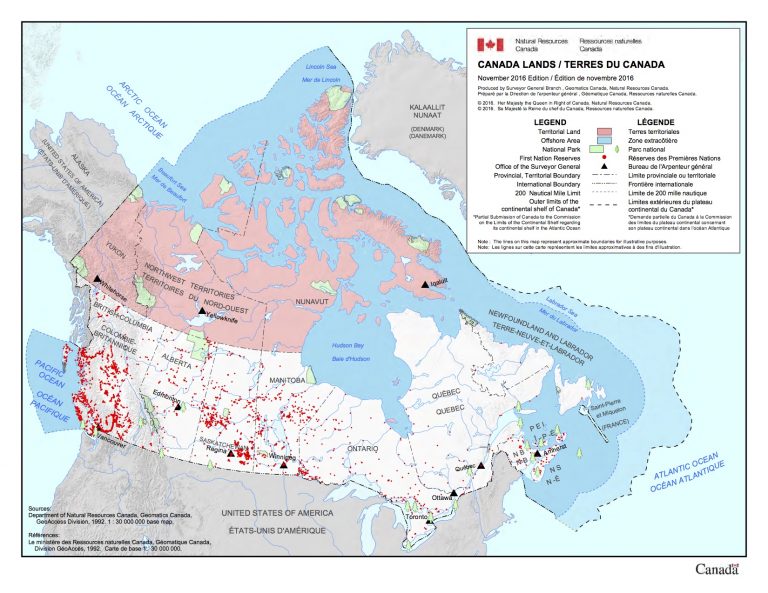

The Canada-US border is often compared to the Mexico-US border, where Border Studies originated and from which Canada-US Border Studies both draws and departs. The Mexico-US border, with its heightened securitization and prominence in US political anxieties, and as a site of dangerous crossings for undocumented migrants, seems to contrast sharply with the Canada-US border. But in approaching the 49th parallel as a site of struggle, we see that for some people within Canada’s boundaries, the border resembles the “herida abierta”—the open wound—that, according to Chicana feminist Gloria Anzaldúa in her seminal text, Borderlands/La Frontera (25), characterizes the Mexico-US border. Border Studies emphasizes power relations between countries on either side of international boundaries, the experiences of people living in borderlands and/or migrating across borders, and the cultural implications of artificially drawn boundaries for the people who cross or who dwell on either side of them. This section examines Canada-US Border Studies scholarship in relation to Anglo-Canadian nationalist, Indigenous, and Black Canadian positions in border texts.

Scholarly Approaches to Canada-US Border Texts

For Anglo-Canadian nationalists, Russell Brown observes, “borders mark off an important difference between south and north” (2). Brown argues that novels such as Mordecai Richler’s St. Urbain’s Horseman (1971) and Janette Turner Hospital’s Borderline (1985) portray border crossings “as literally, as well as psychologically, difficult” (10), emphasizing Canada-US distinctions. Anglo-Canadian nationalist thinking about the border invokes cultural imperialism, the overpowering of Canadian culture by US influence: as Brown explains, “In Canada, the border is seen as protecting the country, making it a place of safe refuge” (9).

Kit Dobson illustrates how poet Dennis Lee’s Civil Elegies (1972)—seeking “a defence against . . . the international threat of the United States” (51)—exudes anxiety about Canadian sovereignty (economic, political, and cultural), bemoaning “bewildered nations” whose “boundaries / diminish to formalities on maps” (Lee 37). Brown and Dobson therefore read the border in Anglo-Canadian nationalist literature as either a protective entity or one that itself needs to be strengthened in order to guarantee Canadian sovereignty.

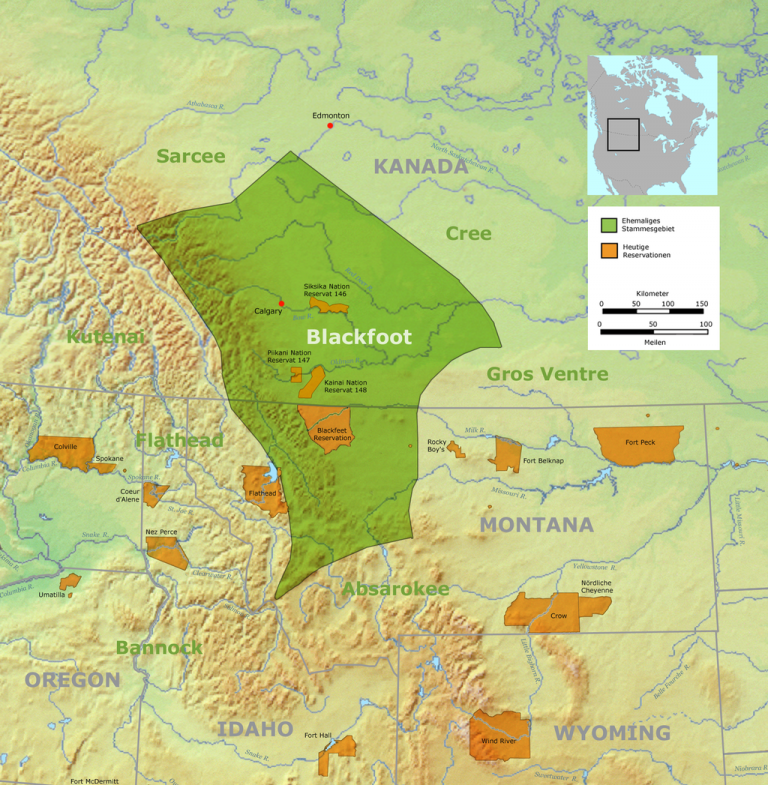

Map of Blackfoot lands. Nikater, via Wikimedia. Public Domain.

As the border is a product of colonial cartography, Indigenous nations, particularly those the border divides, have a radically different view: as Audra Simpson (Mohawk) argues, nation-state borders are “in their space and in their way” (115). In the works of Thomas King, a writer of Cherokee, Greek American, and German American descent and long based in Canada, the Canada-US border, “a destructive line for many First Nations” (Andrews and Walton 602), implicates Canada in imperial power. In King’s short story “Borders” (1993), when the narrator’s mother is asked to declare her citizenship by American and then Canadian border guards, she replies, “Blackfoot” (137). As Jennifer Andrews and Priscilla L. Walton note, the mother’s insistence upon Blackfoot citizenship “demonstrates [how] the 49th parallel can be used” by Indigenous peoples “as a site of resistance to imperialist definitions that preclude . . . self-definition” (607). The mother refuses to consent to the two settler-colonial states’ imposed conceptions of her identity.

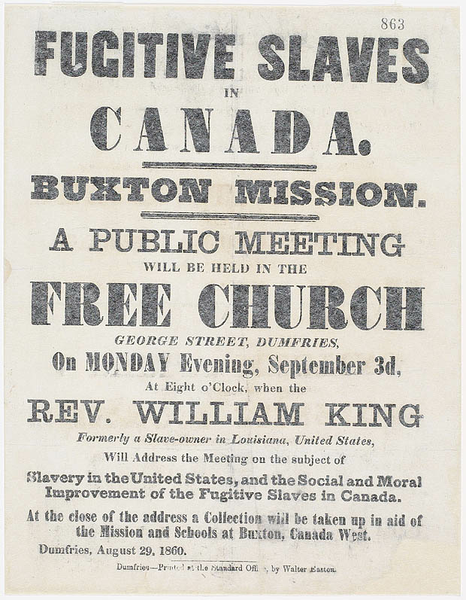

Black Canadian border crossings also reveal the policing of racialized bodies at the nation-state’s threshold. In both scholarship and literature, these crossings “contest the pervasive discounting of slavery in Canada” (Ferguson 243) and undermine recurring cultural representations of Canada defined through whiteness. For example, Lawrence Hill’s The Book of Negroes (2007) contributes to “shattering the safe-haven myth,” in Katherine McKittrick’s words (119). After the American War of Independence from Britain, Aminata joins the Black Loyalist migration to the British colony of Nova Scotia. Although the British advise, “Nova Scotia . . . will be your Promised Land” (Hill 286), the virulent racism and slavery she witnesses suggest otherwise.

“Fugitive Slaves in Canada,” 1860. The Canadian Encyclopedia.

As Rinaldo Walcott demonstrates, in Hill’s earlier novel, Any Known Blood (1997), the author represents Canada as a Black space by tracing five generations of the Black cross-border Cane family: from Langston I’s Underground Railroad experiences of escaping slavery by crossing the border to his Oakville, Ontario-born descendant Langston V’s assembling of family history in Baltimore, Maryland. The novel, Walcott argues, “uncovers the lies of the Canadian nation as a white-only space” (69) while “questioning discreet and separate boundaries” (67), as the Canes’ history so clearly straddles the Canada-US border.

Ric Knowles highlights how Djanet Sears’ play Harlem Duet (1996) presents a cross-border reversal of dominant Canadian narratives: Sears’ Black Canadian protagonist, Billie, finds refuge in Harlem, New York. If Billie’s American sister-in-law praises Nova Scotia as “a haven for slaves way before the underground railroad” (45), then the play demonstrates that Canada “is no Harlem” (Knowles 382).

As this overview of academic research illustrates, Canada-US border scholarship presents the border as a site of struggle in its function and significance. The border’s ineffectiveness against US cultural imperialism (as articulated by Anglo-Canadian nationalists) collides with its very different roles for Indigenous nations and Black Canadians, respectively: a scar of settler-colonial violence; and a gateway to unfulfilled promises.

Research Questions to Consider

- Writer Margaret Atwood characterizes the Canada-US border as a “one-way mirror” (440). What does this metaphor imply? Choose a border text and examine how the work upholds and/or challenges Atwood’s characterization.

- “We didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us” is an immigration activist “rallying cry” in the Mexico-US borderlands (Adams 35). Read Chapter Five, “Borders, Cigarettes, and Sovereignty,” of Audra Simpson’s book Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. How might the immigration activist rallying cry at the Mexico-US border resonate with Indigenous nations that straddle the Canada-US border? What does Simpson’s discussion of the settler-colonial borders impacting upon the Mohawk suggest about both the possibilities and the pitfalls of using Mexico-US Border Studies to illuminate understandings of the Canada-US border? What site-specific contexts affect the ability of Border Studies to “travel” to other locations?

- According to influential Black American activist Malcolm X (1925-1965), “Mississippi is anywhere south of the Canadian border,” a claim that “exempts Canada from prejudice” (Clarke 29). What does “Mississippi” represent to Malcom X and why? Choose a Black Canadian border text, and analyze how this literary work challenges and/or endorses Malcolm X’s assessment.

National Map of Canada Lands, 2016. Natural Resources Canada.

Works Cited

- Adams, Rachel. Continental Divides: Remapping the Cultures of North America. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2009. Print.

- Andrews, Jennifer, and Priscilla L. Walton. “Rethinking Canadian and American Nationality: Indigeneity and the 49th Parallel in Thomas King.” American Literary History 18.3 (2006): 600-17. Print.

- Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 1999. Print.

- Atwood, Margaret. “Canadian-American Relations: Surviving the Eighties.” Second Words: Selected Critical Prose 1960-1982. Toronto: Anansi, 2011. 424-48. Print.

- Brown, Russell. “The Written Line.” Borderlands: Essays in Canadian-American Relations. Ed. Robert Lecker. Toronto: ECW, 1991. 1-27. Print.

- Clarke, George Elliott. Odysseys Home: Mapping African-Canadian Literature. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2002. Print.

- Dobson, Kit. Transnational Canadas: Anglo-Canadian Literature and Globalization. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2009. Print.

- Ferguson, Jade. “Discounting Slavery: The Currency Wars, Minstrelsy, and ‘The White Nigger’ in Thomas Chandler Haliburton’s The Clockmaker.” Parallel Encounters: Culture at the Canada-US Border. Ed. Gillian Roberts and David Stirrup. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2014. 243-59. Print.

- Hill, Lawrence. Any Known Blood. Toronto: HarperPerennial, 1997. Print.

- —. The Book of Negroes. Toronto: HarperCollins, 2007. Print.

- Hospital, Janette Turner. Borderline. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1985. Print.

- King, Thomas. “Borders.” One Good Story, That One. Toronto: HarperPerennial, 1993. 131-45. Print.

- Knowles, Ric. “Othello in Three Times.” Shakespeare in Canada. Ed. Diana Brydon and Irena R. Makaryk. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2002. 371-94. Print.

- Lee, Dennis. Civil Elegies. 1972. Civil Elegies and Other Poems. Concord: Anansi, 1994. Print.

- McKittrick, Katherine. Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2006. Print.

- Richler, Mordecai. Urbain’s Horseman. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1971. Print.

- Sears, Djanet. Harlem Duet. Winnipeg: Scirocco, 1996. Print.

- Simpson, Audra. Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. Durham: Duke UP, 2014. Print.

- Walcott, Rinaldo. Black Like Who? Writing Black Canada. 2nd ed. Toronto: Insomniac, 2003. Print.

©

©