Indigenous and Diasporic Interconnections

Clements’ work—provocative, cutting-edge, theatrically astonishing—has received critical acclaim in reviews in both mainstream newspapers and Indigenous media outlets, both nationally and internationally. In addition, scholarly interest in Indigenous and diasporic interconnections in Clements’ work has grown exponentially, as evidenced by numerous articles and book chapters on her work over the past decade (see the bibliography in the Activities and Resources section for a selection). Canadian literature is often recognized for its cultural diversity and its sharp engagement with issues around multiculturalism, immigration, and diaspora. However—as Rita Wong, Michelle LaFlamme, and others argue—Indigenous writers, like Clements, often provide a different entry point into these conversations by emphasizing their status as First Peoples of this land. In this way, as Sophie McCall contends, a play like Burning Vision exposes how categories of literary or cultural analysis, emerging from debates concerning immigrant groups and the settler nation, can serve to further marginalize or even render invisible Indigenous peoples’ struggles to assert the vitality of their cultures, languages, and claims to land.

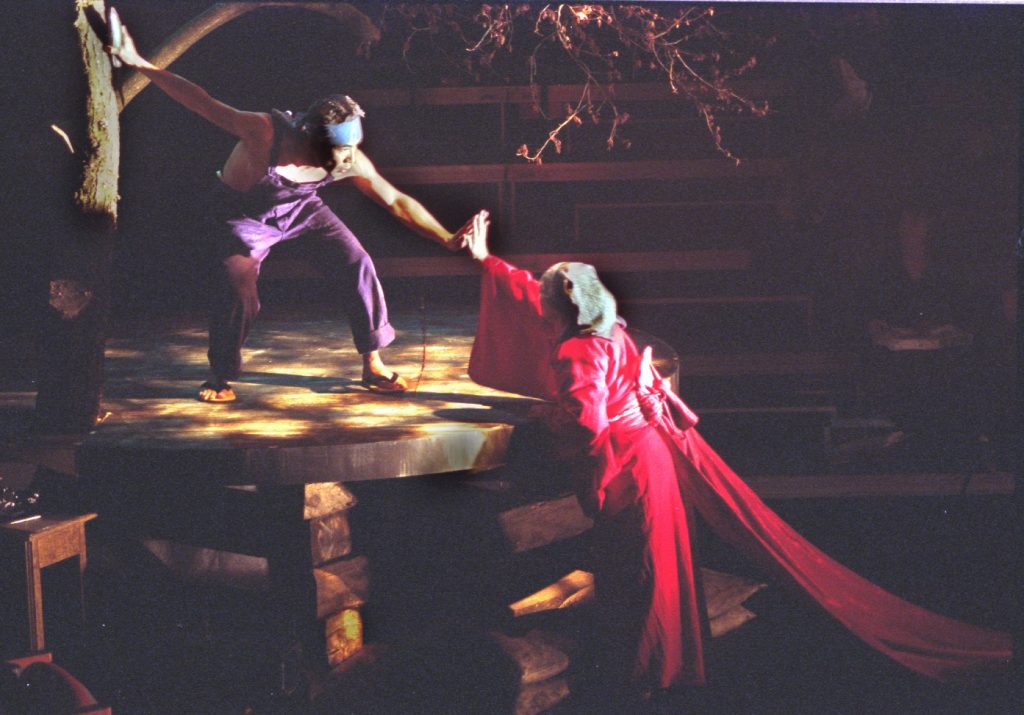

Koji (Hiro Kanagawa) and the Japanese Grandmother (Margo Kane) touch across the boundaries of time and space. Photograph by Tim Matheson. Reproduced with permission from Rumble Theatre and Urban Ink Productions.

Furthermore, as Wong, McCall, Larissa Lai, and Malissa Phung have demonstrated, scholarly discussions around cultural diversity and hybridity often get stuck on comparisons that reassert the centrality of the white, settler identity. Clements’ play Burning Vision offers audience members a means of approaching these issues from a different angle by uncovering what are often underrecognized interconnections between histories, cultures, languages, lands, and migrant and Indigenous peoples. (See the Indigenous and Diasporic Intersections in Canadian Literature chapter for more on these interconnections.) Rita Wong’s article, “Decolonizasian,” reads Burning Vision as a work that asks Canadian literary scholars to realign familiar comparative frameworks of analysis by emphasizing, in her words, “moments of reciprocity and solidarity between racialized bodies” such as “‘Asian’ and ‘First Nations’ characters” (168). For example, Japanese Canadians were labelled as “enemy aliens” during World War II, and were forced to carry identification papers; Indigenous peoples, from 1885 until 1951, as a result of the restrictive policies of the Indian Act, could not leave the reserves without a pass. Japanese Canadians and First Nations peoples encountered one another in former mining towns in British Columbia, where Japanese Canadians were relocated as a result of their expulsion from the coast in the wake of the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. (See the chapter on Joy Kogawa’s Obasan for further investigation on such links.) The relations between Asian diasporas and indigeneity are just one set of cultural and historical interconnections that animate not only the four movements in Clements’ play, but also Wong’s analysis.

Cultural critic James Clifford theorizes the mobility and rootedness of diasporic and Indigenous groups jointly through the homonym “routes and roots.” Burning Vision participates in a similar project by creating characters with multiple identifications and belongings that interweave the local and the transnational, thereby disrupting a familiar pattern in critical debates, in which comparisons between diasporic and/or Indigenous groups often reassert the centrality of a white settler colonial identity. Burning Vision focuses the relations between Asian and Indigenous experiences by comparing them to each other rather than to white settler colonial experiences. We can see these tensions between “routes and roots,” between migrant and Indigenous histories, in many of the characters in the play.

Take, for example, the character of Koji. We are first introduced to Koji as a Japanese boy who is being raised by his grandmother in Japan. The play implies that he is an orphan because his parents have perished during the bombing of Hiroshima. Later in the play, Koji is now a fisherman in Dene territory with whom Rose, a Métis woman, falls in love. Rose sees a connection with Koji whom she describes as “Indian enough from the other side” (105), suggesting his possible roots to the Ainu people, an Indigenous group in Japan. Like Indigenous peoples in Canada, the Ainu were both excluded from and obliged to assimilate into Japanese culture and citizenship (Curran 451-52). Koji, the Japanese / Ainu fisherman, is simultaneously Koji, the victim of the bombing at Hiroshima. He is also the survivor who meets Rose, who is looking for her lost mother, a survivor of residential school.

Koji could also be repositioned in relation to Japanese Canadian history. During World War II, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Japanese Canadians not only were interned in Vancouver and Victoria, BC, but also were uprooted from the west coast and relocated to inland settlements, work camps, or farms. Koji’s encounter with Rose signals his displacement within Canada; similarly, Rose’s missing mother is an emblem of how Indigenous peoples are uprooted: displaced from their homelands through residential schools and other policies of assimilation and genocide. This example of tracing the multiple incarnations of the character of Koji—his roots and his routes—illustrates Wong’s argument of how Clements puts Indigenous and diasporic characters into conversation without necessarily moving the comparison through a white settler identity.

Intertexts with Burning Vision

Along with emphasizing the connections between characters, histories, and geographies, Burning Vision also underlines its relationship to other texts—a concept known in scholarly discussions as intertextuality. An important intertext for the play is Peter Blow’s documentary film, Village of Widows (1999). It examines how people living in the region where the uranium was mined (in and around Port Radium, Northwest Territories) lost many from their community to cancer, including women and children who were in close contact with the workers. Some of the statements made by interviewees in this film reappear almost verbatim in the play.

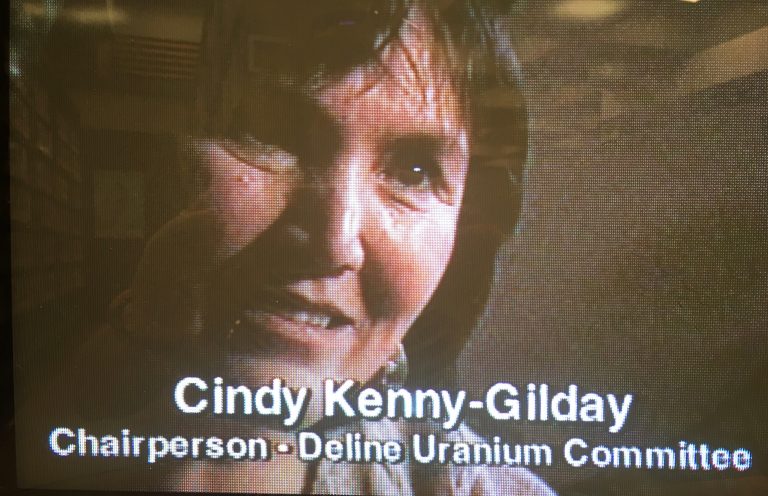

Cindy Kenny-Gilday, Chair of the Deline Uranium Committee, a group of Dene people who went to Japan to pay their respects to the survivors and participate in memorial activities in 1997. Reproduced with permission from Peter Blow and Lindum Films.

Throughout the film, interviewees contribute to an ongoing verbal memorial of those who have passed on. The words of Shirley Baton, daughter of the late John Baton who hauled uranium, open the film: “My dad died of cancer, my aunt died of cancer, my grandmother died of cancer, my mum is suffering because of her sickness, and what about my children? Because I believe once there’s something in a person’s genes it carries on.”

The idea that a family’s genes are imprinted by a history of radiation further emphasizes the themes of interconnectivity and relationality in the play. This doubled sense of correlation between the Dene and Japanese—as the fear of deadly contamination and as the hope for a renewed sense of community connection—remains an insoluble tension in both Blow’s film and Clements’ play.

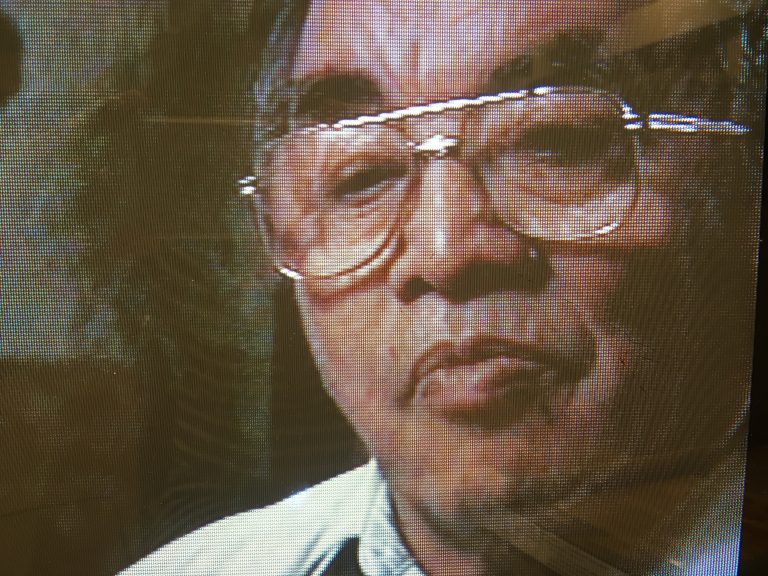

An important interviewee in Village of Widows is George Blondin, a Dene elder, storyteller, and author; one of Blondin’s published books includes a version of a well-known Dene prophecy that is another key intertext for Burning Vision. In 1997, Blondin joined a group of Dene people who travelled to Japan to visit survivors of the Hiroshima bombing. This self-funded trip was meant to acknowledge the shared tragedy and also to establish the deep bonds that now connected these two places. Through this visit, the Dene delegation took ownership over the uranium and the chain of events that it caused, despite the fact that they had very little control over how it was used. Blondin also played the part of the Dene See-er in the 2002 premiere of Burning Vision in Vancouver.

His many stories are collected in books such as When The World Was New (1990), Yamoria The Lawmaker (1997), and Trail of the Spirit (2006), including the prophesy from the 1880s by a visionary who foresaw the potential dangers of the black rock or pitchblende (uraninite) that is abundant on Dene lands (see Blondin’s retelling, “An Old Timer’s Prophecy,” in When the World Was New, 78-9). In Burning Vision, Clements dramatizes how the prophecy fuses the past, present, and future through the play’s innovative staging, in which four worlds collide and separate as the characters move between them.

George Blondin from Village of Widows. Director Peter Blow. Reproduced with permission from Peter Blow and Lindum Films.

Research Questions to Consider

- “My baby is going to be mixed again, but I am happy about that ’cause I think he can give the world my hope” (114). As a figure that brings together Indigenous and Asian histories and experiences, Rose and Koji’s unborn baby seems to be a symbol of hope in which a world free of racism and exclusion is imagined. However, moments after Rose utters these words, a blinding white light and explosion occurs, signalling the detonation of one of the 1945 atomic bombs. Does the baby remain unborn, perishing when the atomic bomb explodes? Or is the Grandson Koji, whom we meet later, Rose and Koji’s son? Why does the play simultaneously suggest the baby as a symbol of hope and of destruction?

- In her article “Asian-Indigenous Relationalities,” Malissa Phung explores the relations between Asian and Indigenous communities within a settler colonial structure and the possibilities for solidarity. Through her analysis of SKY Lee’s Disappearing Moon Cafe, and in particular the sections in which Lee describes how Indigenous communities helped early Chinese migrants survive in Canada, she argues for the importance of acknowledging the “historical debt” that Chinese Canadians owe to Indigenous peoples. Marie Clements’ Burning Vision similarly argues for the need to remain mindful of historic relations and acknowledge how they shape the present moment. However, Phung also asks

how the contemporary inheritance of this historical debt could work when not all Chinese Canadians have genealogical ties to the Head Tax generation. The majority of today’s Chinese Canadians constitute a post-1967 immigrant demographic vastly different from the early Chinese settlers in class, culture, language, spiritual beliefs, ethno-national origins, diasporic affiliations, and political ideologies. Could solidarity calls to such a heterogeneous community to claim these historical Asian-Indigenous relations of indebtedness supersede internal differences often thought to be too insurmountable to overcome? (62)

Can we ask similar questions of the Indigenous and Japanese communities that Burning Vision examines? Can the kinds of relations and responsibilities that the Dene imagine as having to the Japanese after the atomic bombings be extended to include younger generations of Japanese communities to the Dene? Can these relations and responsibilities be extended to other Indigenous, non-Dene communities?

- Read George Blondin’s “An Old Timer’s Prophesy” in his book When The World Was New (78-9). This is the book that Marie Clements said she carried around for ten years while she was conceptualizing and writing this play. It is an important intertext for Burning Vision. How does reading “The Prophecy” influence your understanding of the title or the play as a whole? You may also want to listen to Blondin’s retelling of the prophesy with some variations in Magnus Isacsson’s film, Uranium (1990).

- Watch the documentary film, Village of Widows, directed by Peter Blow, an intertext for Clements’ play. In addition to the words of Shirley Baton and George Blondin we discussed earlier, what are the other points of connection between the film and Clements’ play? How does the history that this film documents help you understand the connections that this play is trying to make?

Works Cited

- Blondin, George. Trail of the Spirit: The Mysteries of Medicine Power Revealed. Edmonton: NeWest, 2006. Print.

- —. When The World Was New: Stories of the Sahtu Dene. Yellowknife: Outcrop, 1990. Print.

- —. Yamoria the Lawmaker: Stories of the Dene. Edmonton: NeWest, 1997. Print.

- Blow, Peter, dir. Village of Widows. Peterborough: Lindum Films, 1999. Film.

- Clements, Marie. Burning Vision. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2002. Print.

- —. Reading and Talk on Burning Vision at Simon Fraser University. Burnaby: Simon Fraser University. November 26, 2009. Talk.

- Clifford, James. “Diasporas.” Cultural Anthropology 3 (1994): 302-38. Print.

- Curran, Beverley. “Invisible Indigeneity: First Nations and Aboriginal Theatre in Japanese Translation and Performance.” Theatre Journal 59 (2007): 449-65. Print.

- Isacsson, Magnus, dir. Uranium. 1990. Film.

- LaFlamme, Michelle. “Speaking Up, Speaking Out, Or Speaking Back: The Signposts Are in the Right Direction.” TRiC / RTaC2 (2010): xxviii-xxx. Print.

- —. “Theatrical Medicine: Aboriginal Performance, Ritual and Commemoration.” TRiC / RTaC2 (2010): 107-17. Print.

- Lai, Larissa. “Epistemologies of Respect: A Poetics of Asian/Indigenous Relation.” Critical Collaborations: Indigeneity, Diaspora, and Ecology in Canadian Literary Studies. Smaro Kamboureli and Christl Verduyn. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2014. 99-126. Print.

- Lee, SKY. Disappearing Moon Cafe. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1990. Print.

- McCall, Sophie. “Linked Histories and Radio-Activity in Marie Clements’ Burning Vision.” Trans/acting Culture, Writing, and Memory: Essays in Honour of Barbara Godard. Eva C. Karpinski, Jennifer Henderson, Ian Sowton, and Ray Ellenwood. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2013: 245-65. Print.

- Phung, Malissa. “Asian-Indigenous Relationalities: Literary Gestures of Respect and Gratitude.” Canadian Literature 227 (2015): 56-72. Print.

- Wong, Rita. “Decolonizasian: Reading Asian and First Nations Relations in Literature.” Canadian Literature 199 (2008): 158-80. Print.

©

©