Farah Moosa

Joy Kogawa’s novel Obasan (1981) is a powerful narrative about a woman’s attempt to understand her familial past and the historical and cultural legacies she has inherited as a Japanese Canadian. The novel is primarily set in Granton, Alberta in 1972 and revolves around the experiences and memories of its central character, Naomi Nakane. Naomi, a thirty-six-year-old schoolteacher living in Cecil, Alberta, returns home to Granton upon the death of her uncle, Isamu (Sam) Nakane. Naomi’s return triggers memories of her experiences growing up in British Columbia and Alberta during World War II. It also results in new knowledge about her mother’s and maternal grandmother’s wartime experiences in Japan.

Obasan is the first novel that documents the experiences of Japanese Canadians before, during, and after World War II, and it has educated generations of readers about the forced uprooting, dispossession, and dispersal of over 23,000 Japanese Canadians from British Columbia’s coast to interior areas of the province and across Canada (Miki 201, 2-3). A much celebrated literary work, Obasan has received multiple awards, including the Books in Canada First Novel Award (1981) and the Canadian Authors Association Book of the Year Award (1982). Other works by Kogawa, including her 1992 novel Itsuka (which was revised and republished as Emily Kato in 2005) and her children’s book Naomi’s Road (1986) continue to tell the story of Naomi Nakane.

Decades after its first publication, Obasan still captures the attention of many readers and is widely taught in schools, colleges, and universities in Canada. The novel has also received a great deal of critical attention—there are a number of book chapters and articles on Obasan. This chapter serves as an introduction to the novel and some of the scholarly conversations that surround it. In particular, it explores the important and interrelated themes of silence and speech, and memory and history; and it suggests some strategies for close-reading the novel.

Joy Kogawa

Joy Kogawa is intimately connected to the history and the communities that she writes about in Obasan. She was born in 1935 to first-generation Japanese Canadians in Vancouver, British Columbia, and, like other Japanese Canadians, she was forcibly relocated with her family during and after World War II (Wilson 341). Her family was sent to an internment camp in Slocan when she was six years old (Kogawa and Nakayama 144). After the war, Kogawa and her family relocated to Coaldale, Alberta (“Joy Kogawa”), as Japanese Canadians were not allowed to return to the West Coast until April 1, 1949. Kogawa completed high school in Coaldale before studying at several postsecondary institutions, including the University of Alberta, the Royal Conservatory of Music, and the University of Saskatchewan (“Joy Kogawa”). She was later involved in the struggle for redress from the Canadian government.

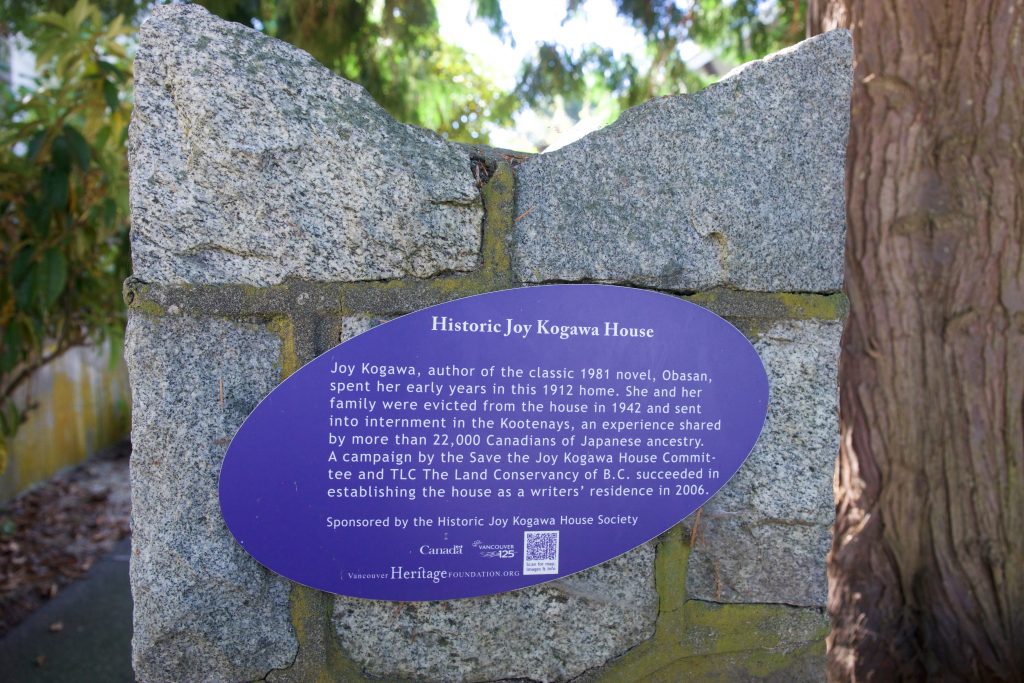

Kogawa was made a member of the Order of Canada in 1986 and a member of the Order of British Columbia in 2006. She was also awarded the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) National Award of Merit in 2001 and Japan’s Order of the Rising Sun in 2010. Her childhood home in Vancouver, the Historic Joy Kogawa House, has been preserved as a symbol of the history of Japanese Canadians and serves as a literary and cultural centre.

Japanese Canadian Internment

In the immediate aftermath of Japan’s December 7, 1941 attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, the Canadian government (under the War Measures Act) declared all people of Japanese heritage to be “enemy aliens,” and uprooted individuals of Japanese ancestry living within 100 miles of British Columbia’s coast to inland areas of the province and other parts of Canada (Miki 2-3). More than 23,000 people, most of whom were Canadian-born or naturalized citizens, were forced to leave their homes; their properties, businesses, and personal belongings were confiscated and sold (Miki 2-3). Many Japanese Canadians were held in the livestock buildings on the Pacific National Exhibition (PNE) grounds at Hastings Park in Vancouver (referred to as “the Pool” in Obasan) in appalling living conditions before being dispersed to other locations (e.g. internment camps in British Columbia, sugar beet farms in Alberta). In 1945, after Japan surrendered following the bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, the Canadian government forced Japanese Canadians still living in inland areas of British Columbia to either move east of the Rocky Mountains or be repatriated to Japan even if they had never been or lived there. By 1949, when Japanese Canadians were finally allowed to return to the West Coast, little or nothing remained of their pre-wartime lives (Miki 3). Many individuals and families ended up staying in their new locations (Miki 3).

“Building A, ‘Section of Women’s Dormitory – (Formerly Live Stock Building)’: Hastings Park, Vancouver, BC” (circa 1942). Photographed for the BC Security Commission by Leonard Frank. Nikkei National Museum 1994-69-3-20.

Obasan was written and published in the context of the Japanese Canadian redress movement, which sought an official acknowledgement of and compensation for the government’s actions against Japanese Canadians during and after the war. A settlement was reached between the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) and the Canadian government on September 22, 1988. On that date, a passage from Kogawa’s novel was also read in Parliament (“1988: Government apologizes to Japanese Canadians”).

Knowing this historical context is a first crucial step in understanding both Kogawa’s artistic aims in Obasan and scholars’ critical engagement with the novel. The next section of this chapter explores some of the ways scholars approach the novel, specifically with regard to language and its connection to history.

Questions to Keep in Mind When Reading Obasan

- “Obasan” means “aunt” in Japanese. Naomi refers to her aunt, Ayako Nakane, as “Obasan,” though the term may also be used to address an older woman. What is the significance of the novel’s title, Obasan?

- How does Kogawa draw our attention to the long history of Japanese Canadians in Canada?

- What official and unofficial documents does Kogawa incorporate throughout her novel? What is the effect of these documents on the narrative?

Works Cited

“Japanese Canadians on the train; Slocan Valley, BC” (circa 1942). Photographed for the BC Security Commission by Leonard Frank. Nikkei National Museum 1994-69-4-29.

- “Joy Kogawa.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. 2014. Historica Canada. 13 May 2016.

- Kogawa, Joy. Obasan. 1981. Toronto: Penguin, 2017. Print.

- Kogawa, Joy and Timothy Nakayama. Recollection. Too Young to Fight: Memories from Our Youth During World War II. Comp. Priscilla Galloway. Toronto: Stoddart, 1999. 134-49. Print.

- Miki, Roy. Redress: Inside the Japanese Canadian Call for Justice. Vancouver: Raincoast, 2005. Print.

- Wilson, Sheena, ed. Joy Kogawa: Essays on Her Works. Montreal: Guernica, 2011. Print.

- “1988: Government apologizes to Japanese Canadians.” The National. 22 Sept. 1988. CBC Digital Archives. Web. 13 May 2016.

©

©