The Future(s) of Indigenous Horror: Moon of the Crusted Snow

In this chapter, we will explore approaches to the topic of Indigenous horror as it applies to Anishinaabe writer Waubgeshig Rice’s apocalyptic horror novel Moon of the Crusted Snow. This introduction provides context for the novel by discussing its place within recent trends in genre studies and Indigenous literary studies. In the following sections, we will consider a handful of critical approaches to help guide our reading of the novel before turning to an analysis of key sections from the text itself.

A Woman Tenderfoot by Grace Gallatin Seton-Thompson

In 1900, young American suffragist Grace Gallatin Seton-Thompson published her first book, an account of her extended 1897 camping trip in western regions of the United States and Canada. This chapter contextualizes A Woman Tenderfoot within Canadian literature and within the genre of travel writing that was so popular at the time. It then suggests several theoretical approaches for reading A Woman Tenderfoot more closely.

An Introduction to the Short Story in Canada: Reading Alice Munro’s Who Do You Think You Are?

This chapter introduces the short story as a literary genre, and discusses the short story cycle as a particularly important genre in Canada. It offers some suggestions for analyzing short stories from print culture and feminist perspectives, and it turns to Alice Munro’s 1978 short story cycle Who Do You Think You Are? as a case study in putting these perspectives to work.

Literary Censorship and Controversy in Canada

This chapter introduces you to literary censorship in Canada, looking both at positions taken by Canadian scholars on the practice of censorship and its effects, as well as at specific examples. We will analyze controversies around three texts to better see how the censorship of Canadian literature works in practice: Timothy Findley’s The Wars (1977) and Beatrice Culleton Mosionier’s In Search of April Raintree (1983) provide examples of censorship where the authors themselves were involved in contesting or responding directly to critics in their texts; Raziel Reid’s When Everything Feels Like the Movies (2014) provides an example of a contemporary attempt to strip a novel of its literary award on the basis of its allegedly controversial content.

Joy Kogawa’s Obasan

Joy Kogawa’s novel Obasan (1981) is a powerful narrative about a woman’s attempt to understand her familial past and the historical and cultural legacies she has inherited as a Japanese Canadian. Decades after its first publication, Obasan still captures the attention of many readers and is widely taught in schools, colleges, and universities in Canada. The novel has also received a great deal of critical attention—there are a number of book chapters and articles on Obasan. This chapter serves as an introduction to the novel and some of the scholarly conversations that surround it. In particular, it explores the important and interrelated themes of silence and speech, and memory and history; and it suggests some strategies for close-reading the novel.

Dionne Brand: No Language is Neutral

Dionne Brand’s No Language Is Neutral (1990) is a set of poems that can be understood as a meditation on migration. The book addresses the theme of movement from one location to another as it describes a journey from the Caribbean to Canada. In doing so, it outlines (and asks questions about) a conception of identity that is influenced by movement, dislocation, and variability. The following sections of this chapter summarize some scholarly debates that have taken place around No Language Is Neutral and outline some strategies for interpreting how Brand treats the experience of migration and related topics.

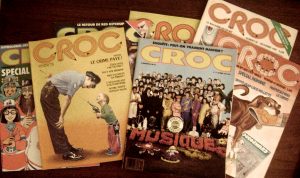

Comics and Canadian Literature

Some of the most significant names in Canadian literature—people like author Margaret Atwood and poet bpNichol—have throughout their careers played with comics as part of their larger body of work. Literary scholars have often paid attention when “serious” writers engage in comics, such as Carl Peters in his collection bpNichol Comics, or Reingard M. Nischik’s attention to Atwood’s comics in her Engendering Genre. But how do we analyze comics produced in Canada by comics creators? We now see comics appearing more frequently in college and university courses, including in Canadian literature classes. Yet the history, scholarship, and language of literary study do not always neatly transpose onto the world of comics. This chapter is designed to introduce new comics readers to the history of creating and evaluating comics in Canada and to the practice of reading them as scholars.

Marie Clements’ Burning Vision

The play Burning Vision, by Métis Dene playwright and filmmaker Marie Clements, is an extraordinary exploration of interconnectedness across diverse histories, cultures, languages, and places. The play traces several intertwined historical trajectories, but the more familiar historical event it narrates is how the atomic bombs that were dropped by the United States on Nagasaki and Hiroshima during World War II were made from uranium mined from the lands of the Sahtu Dene First Nation near Port Radium, Northwest Territories. Although this event indelibly and permanently connected these two places in terms of trauma, disease, and environmental poisoning, it also later generated more positive relations of responsibility, accountability, and mutual recognition.

Listening to Canada: The Weakerthans’ “One Great City!”

This chapter considers the roles of locality and identity in John K. Samson’s song lyrics, particularly through Samson’s evocations of the people, landmarks, and history of Winnipeg, Manitoba in “One Great City!” Locality means the particular place or position of something, and is related to the idea of the “local,” which connotes a specialized knowledge about a certain place or community by virtue of being part of it. Samson, a lifelong Winnipeg resident frequently termed “the poet laureate of Winnipeg rock” (Sorensen), has often made the city his unlikely muse, saying, “I think of Winnipeg as my subject . . . that I’m always trying to get right. . . . Even if I leave, I’ll always be writing about this place” (qtd. in Chong 77).

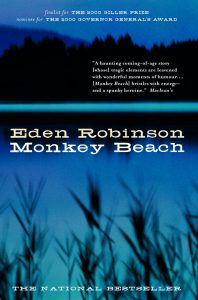

Monkey Beach by Eden Robinson

Haisla/Heiltsuk writer Eden Robinson’s first book, a collection of stories called Traplines, was published to critical acclaim in 1996. Robinson then adapted one story from the collection, Queen of the North, into her debut novel, Monkey Beach, which was shortlisted for the 2000 Governor General’s Award and the Giller Prize, and won the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize.

©

©