Recent decades have seen a growing recognition of the cultural importance of comics as a storytelling medium with many fictional and non-fictional genres written for a wide range of ages. The growing recognition of comics is in large part due to different institutional modes of valuing, most notably, in terms of marketing, publishing, and awards.

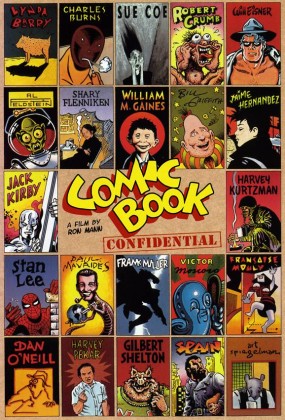

The Genie Award-winning documentary Comic Book Confidential (1988)—researched in part in the extensive comic book collection of bpNichol, Canada’s first alternative comic writer (Bell 143)—offered a broad introduction to American comic books for many, drawing attention to the rich variety of expressions emerging at the time. This included Art Spiegelman’s emerging prominence as a creator, publisher, and promoter of the medium. Spiegelman would go on to win the Pulitzer Prize for his two-volume comic about the Holocaust, Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, in 1992. Maus has played a crucial role in the rising prominence of comics in academia (as of July 2014, the MLA Bibliography notes that Maus is cited in 145 scholarly works). Comics continue to grow in acceptance as an academic subject, evidenced by the increasing numbers of articles, journals, books, and conferences featuring or dedicated to them.

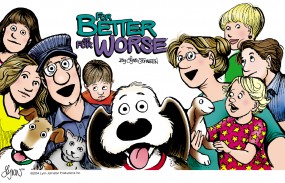

Awards have come to play a more important role in promoting comics, especially in recent years. For example, Lynn Johnston, one of the most widely known Canadian comic strip creators, was the first woman and Canadian to win the American National Cartoonists Society’s Reuben Award, in 1985. She was also nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in 1993, a year after Spiegelman won his. She has won several other awards, has been granted numerous honorary degrees, and has been made a member of the Order of Manitoba and the Order of Canada. Her strip, For Better or For Worse (1979–2008, but still reprinted regularly), is one of the most widely known comic strips in Canada.

Recent years have seen the development of two Canadian-specific comics awards to promote comics and graphic novels: the Doug Wright Awards (est. 2004) and the Joe Shuster Awards (est. 2005). The Doug Wright Awards are named after the early and influential cartoonist best known for his silent comic strip Little Nipper (1949–1980), whose main character features on the award’s seal. The Joe Shuster Awards are named for Joe Shuster, a Canadian artist who co-created Superman with Jerry Siegel. At these awards, the chosen cartoonist is also inducted into the associated Canadian Cartoonist Hall of Fame.

These two awards cover a range of work that often overlaps, although the Wrights focus more on alternative works and the Shusters more on mainstream comics. These awards have built a platform for recognizing comics in Canada as a valuable medium of expression. The Joe Shuster Award is a “national award that honours and raises the awareness of Canadians that create, publish and sell comics, graphic novels[,] and webcomics,” with the goal of raising the public profile and value of comics and their creators in Canada (“Information” n. pag.).

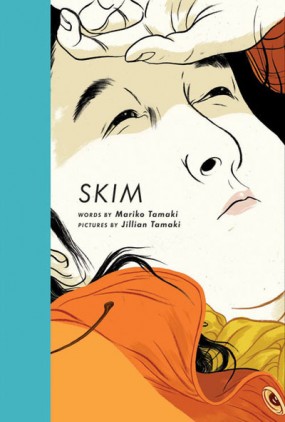

Skim and the Governor General’s Awards

Skim by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki (Groundwood, 2008) Text copyright © 2008 by Mariko Tamaki, illustrations copyright © 2008 by Jillian Tamaki. Permission granted from Groundwood Books Limited, Toronto.

The developing awards culture is helping establish comics and graphic novels as a valuable form of expression in Canadian culture. However, there remain vestiges of institutional stigma against comics in Canada’s literary awards culture.

One notable example is the case of Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki’s young adult (YA) graphic novel, Skim, which won a Doug Wright Award and was nominated for a Governor General’s Literary Award (GGs) in 2008. Currently the GGs, administered by the Canada Council for the Arts, explicitly do not accept any graphic novels outside of the category of children’s and YA books. Since it could be categorized as YA fiction, Skim fit the children’s literature award’s nomination criteria. However, another problem arose.

The nomination was only for Mariko, who penned the words, excluding Jillian, who penned the images. This nomination suggested that the award committee prioritized the words over the images, reflecting a common bias against the image. In response to this slight against Jillian, Chester Brown and Seth wrote an open letter in the National Post, urging the committee that she be included in the nomination. Many major comics creators across North America, including Art Spiegelman, publically endorsed their letter.

Brown and Seth were concerned that Jillian Tamaki’s lack of a nomination “highlight[s] how [their] medium is misunderstood” (n. pag.). The graphic novel is not an illustrated novel in which

the illustrations serve as a form of visual reinforcement…. [I]n graphic novels, the words and pictures BOTH tell the story, and there are often sequences (sometimes whole graphic novels) where the images alone convey the narrative. The text of a graphic novel cannot be separated from its illustrations because the words and the pictures together ARE the text. Try to imagine evaluating SKIM if you couldn’t see the drawings. Jillian’s contribution to the book goes beyond mere illustration: she was as responsible for telling the story as Mariko was.

For comics creators, text should not be prioritized over images. While some comics employ more or less language, and more or less distinct imagery, these cannot be separately evaluated and prioritized, but must be recognized together.

Brown and Seth argue that, rather than making a separate category, graphic novels should be seen as literary products on par with prose works in the GGs. These works accomplish their effects through the collaborative interaction between text and image. Recognition of this collaborative quality in graphic novels and comics would allow, “both of the enormously talented creators of this book to be honoured together for their achievement.” Although the GGs did not revise their nomination to include Jillian that year, the nomination criteria for the children’s fiction category were adjusted the following year, 2009. That year, Harvey, the graphic novel by Hervé Bouchard and Janice Nadeau, won the Governor General’s Award for children’s literature in French. However, that this award is granted only to graphic novels intended for children and youth suggests that comics are not yet be valued as they might be.

Works Cited

- Bell, John. Invaders from the North: How Canada Conquered the Comic Book Universe. Toronto: Dundurn, 2006. Print.

- Gabilliet, Jean-Paul.

Comic Art and bande dessinée: From the Funnies to Graphic Novels.

The Cambridge History of Canadian Literature. Ed. Coral Ann Howells and Eva-Marie Kröller. New York: Cambridge UP, 2009. 460–77. Print. (Link) - Mitchell, W. J. T.

Showing Seeing: a Critique of Visual Culture.

Journal Of Visual Culture 1.2 (2002): 165–81. Print. - Brown, Chester, and Seth.

An Open Letter to the Governor General’s Literary Awards.

Rpt. inComics’ Big Guns Take Aim at the Governor General’s Literary Awards.

Eureka. Brad Mackay. 12 Nov. 2008. Web. 11 Feb. 2014. (Link) Governor General’s Literary Awards.

Canada Council for the Arts, n.d. Web. 9 Jan. 2014. (Link)Information about the Awards.

Joe Shuster Awards. 2011. Web. 20 Feb. 2014. (Link)

©

©