Comics include a range of forms and genres, including the popular graphic novel, and go by a variety of names like cartoons, comix, the funnies, graphica, graphic literature, sequential art, and visual literature. Comics has remained the most popularly accepted general term, with the recognition that comics aren’t always funny. The term comics can impliy that most graphic art is comical, but scholars use comics as a way of acknowledging the popularization of the genre in newspaper funny pages, which typically display a series of comic strips, often sold to many newspapers through agencies called syndicates. While debates continue as to how to properly define comics (Groensteen and Bell have both written helpful introductions to the topic), they typically include sequences of panels with both words and pictures. As a genre, comics are dynamic; they can be wordless and they can complicate sequential left-to-right reading practices.

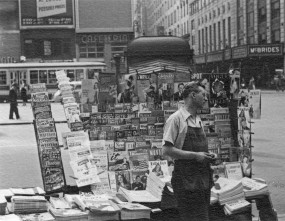

Pulp vendor, June 1942. Location and photographer unknown. From the collection of William Lampkin and ThePulp.net

Comics have proven very popular in Canada and the United States since their beginnings in newspapers and comic books in the late nineteeth and early twentieth centuries (Gabilliet provides a concise overview of English comics from this period). Street vendors and tobacconists commonly sold comics alongside pulp magazines. Comics in English Canada went through a notable Golden Age between 1940 and 1947, spurred on by wartime laws that cut off the import of American comics. The boom developed popular patriotic heroes like Johnny Canuck and Nelvana of the Northern Lights. However, after the war, the American comics, with their much bigger print runs and distribution networks, drove the Canadian cartoons out of business (Bell 41–104; Gabilliet 463–67).

While comics were ubiquitous in popular culture, in the late 1940s and 1950s, parents, religious leaders, and politicians in Canada and the United States grew concerned that some comics, especially horror and crime comics, inspired delinquency and illiteracy (Bell 87–104). Horror and crime comics were banned in Canada and then in the US. From 1950s to the 1970s, comics publishing in Canada almost came to a complete standstill, except for government sanctioned educational comics, newspaper strips like Doug Wright’s Little Nipper, and “underground comix.”

In the late 1960s, comics began to make a comeback through small press and self-publishing ventures (Bell 105–38). For instance, poet bpNichol published some of the first avant-garde comics through his own presses, grOnk and Ganglia, distributing them by hand and through the mail. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, self-publishing helped establish the careers of several notable Canadian cartoonists. For example, Dave Sim self-published his popular magnum opus Cerebus, and other major figures like Chester Brown and Seth began by self-publishing as well. Small presses like Coach House, Arsenal Pulp, and Conundrum also publish comics. Magazines and especially newspapers continue to play a significant role in supporting comic strips, both through mainstream syndicated works like Lynn Johnston’s For Better or For Worse, and through non-syndicated contributions to smaller newspapers, such as David Collier’s comics (both cartoonists have also released books collecting their strips). Furthermore, alternative newspapers like Vancouver’s The Georgia Straight have promoted unconventional cartoonists like Rand Holmes and David Boswell.

The Canadian comics publisher Drawn and Quarterly, founded in Montreal in 1990 by Chris Oliveros, has become a major locus of independent and alternative comics, helping to establish the careers of Chester Brown, Guy Delisle, Julie Doucet, and Seth. It is now a cornerstone of alternative comics publishing in North America alongside Conundrum, Koyama, Fantagraphics, Oni, and Top Shelf.

Although there are no large-scale mainstream comics publishing houses in Canada, a range of alternative publishing institutions helped develop and maintain the careers of a small cadre of cartoonists. Others, like Joe Shuster, the co-creator of the Superman series, went to the US. The dominant American publishing industry continues to attract and sustain lots of Canadian talents, like popular cartoonist Jeff Lemire, who lives in Toronto but works for and publishes through American companies DC and Top Shelf, or like Bryan Lee O’Malley, who lives in Los Angeles and published his popular Scott Pilgrim series through Oni in Portland.

An especially notable success story is that of Canadian cartoonist Todd McFarlane, who worked as an artist for Marvel Comics in the US. In 1992, he left Marvel with a group of others to protest the publisher’s refusal to grant them ownership over their characters. Led by McFarlane and Rob Liefeld, this group started their own publishing house, Image Comics. McFarlane went on to develop the top-selling independent superhero comic, Spawn, and a multimedia empire, for which he was inducted into the Canadian Comic Book Hall of Fame in 2011. The feature documentary from The National Film Board of Canada called Devil You Know: Inside the Mind of Todd McFarlane gives an in-depth look into his life and work.

Since the 1970s, comics artists have found many ways to develop their form and content in underground self-published books, newspapers, small presses, and mainstream publishers. Canadian underground and alternative cartoonists and their publishers have contributed to the development of a wide range of genres and styles in contemporary comics.

Graphic Novels, Web Comics, and Comics Scholarship

In part due to the growing diversity of comics as well as a growing interest in popular culture, academic interest in comics has grown. The successful marketing and popularization of the term “graphic novel” began in 1978 with Will Eisner’s book, A Contract with God. The term quickly caught on and likely helped draw attention to the medium. While “graphic novel” is a somewhat problematic term—especially because it can be used to exclude non-fiction comics like Chester Brown’s Louis Riel: A Comic-strip Biography (Rymhs 76–78)—the reference to the established literary form of the novel helped associate comics more directly with traditional literary institutions such as libraries, schools, and universities. This association helped develop comics’ credibility and acceptability as a serious storytelling art form (Gravett 3). Furthermore, the growth in media, film, and cultural studies also helped make room for alternate forms of storytelling within the academy. Now, newspapers and literary journals, including Canadian Literature, regularly review comics and graphic novels.

The growing institutional recognition of comics helps develop and support the social and cultural value of comics, which in turn likely raises publishers’ interest in them. Major book and art publishers like Norton and Picador are publishing alternative comics alongside smaller presses like Fantagraphics. Furthermore, the mainstream American comics publishers DC Comics, Marvel Comics, Dark Horse Comics, and Image Comics have broadened their portfolios to include a wide range of writers and artists and their non-superhero protagonists (especially through the DC imprint, Vertigo).

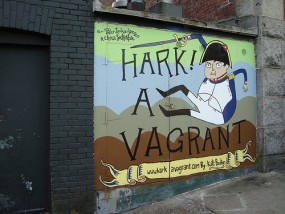

A fan tribute to Hark! A Vagrant by Kate Beaton in Halifax, Nova Scotia. By karenjeane, CC BY-NY 2.0

Changing technologies have also helped advance the way comics are produced and disseminated. With the digital interface of the Internet, comics can be presented on a potentially “infinite canvas” (McCloud). Strips are more easily shared, can go on as long as its creator wants and in any direction, unconstrained by page margins and costs associated with (colour) printing, and can integrate dynamic elements like animations or popup content. Now, cartoonists can produce both print and digital media. For example, the popular, witty, and award winning Hark! A Vagrant by Kate Beaton is a successful webcomic whose strips have been reprinted as calendars, art prints, and in books. Her work was featured in The Best American Comics 2013 and Drawn and Quarterly published a selection of online strips as a book in 2011. In short, digital technologies present important opportunities for creators and publishers to develop comics in new and exciting ways.

Works Cited

- Bell, John. Invaders from the North: How Canada Conquered the Comic Book Universe. Toronto: Dundurn, 2006. Print.

- Gabilliet, Jean-Paul.

Comic Art and bande dessinée: From the Funnies to Graphic Novels.

The Cambridge History of Canadian Literature. Ed. Coral Ann Howells and Eva-Marie Kröller. New York: Cambridge UP, 2009. 460–77. Print. (Link) - Gravett, Paul. Graphic Novels: Everything You Need to Know. New York: Collins, 2005. Print.

- Groensteen, Thierry. The System of Comics. Trans. Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2007. Print.

- McCloud, Scott.

The

Scott McCloud. Feb. 2009. Web. 14 Nov. 2013.Infinite Canvas.

- Rymhs, Deena.

David Collier’s Surviving Saskatoon and New Comics.

Canadian Literature. 194 (2007): 75–92. Print. (PDF)

©

©