Betty Friedan, 1960. Photo by Frank Palumbo, New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection. Public domain: United States Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons

Once political rights and access were established for most women in Canada, feminists continued to advocate for reproductive, marriage, wage, and property rights. These rights dealt with the individual, and a woman’s rights over her body. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) is a pivotal text for the foundation of second-wave feminism. Friedan’s text is so important because it describes the strange phenomena of widespread unhappiness in women enjoying the relative comfort of middle class North American domestic life. The issue was that these women seemingly had it all—good suburban home, a husband, children, the right to vote, and the opportunity to get a university education—and yet they were deeply unhappy and unfulfilled with their lives. They wanted more, and yet they were unsure how to articulate, and draw attention, to exactly what was wrong. Friedan’s description of this sense of emptiness, also known as “the problem that has no name” (57), relied on an understanding of the effects of structural gender inequality on women, and the way that feminine happiness was tied to the home. Friedan largely places blame on media representations of women, especially women’s magazines, which propagated the image of the North American housewife as the ideal woman and the home as the ideal space for women. (See the chapter on Ana Historic for a literary representation of the effects of this problem that has no name.)

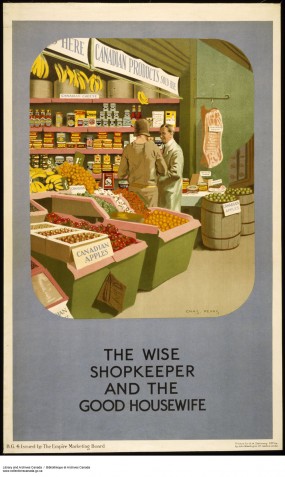

A poster produced by the Empire Marketing Board to promote trade between Great Britain and Canada. The posters were part of an extensive publicity campaign that also extended into schools. Library and Archives Canada: 1926–1934, Promo Québec / accession no. 1983-27-238, C-126223

According to Friedan, fewer and fewer women were entering the workforce and “[m]any women no longer left their homes, except to shop, chauffeur their children, or attend a social function with their husbands. Girls were growing up in America without ever having jobs outside the home” (60). Feminine fulfillment after world war two, according to Friedan, became tied to being a housewife and mother (61). Second-wave feminist scholars drew particular attention to the ways in which public and private spaces were gendered in literature and culture, and second-wave feminist authors likewise drew attention to the lives of girls and women within gendered spaces.

One of the ways that some critics tried to discredit second-wave feminist activism was to say that these women were taking up personal issues in public, and that implicitly these were issues that were best decided within the home and not at the level of the state. One of the rallying cries of second-wave feminism was that the personal is political. This meant both that personal issues had political import for women and also that there was a politics around who got to say what was, and was not, an appropriate issue for public discussion. Beyond improving material conditions and access to public institutions, mid-twentieth century feminists worked to change not only the perception of women in the public sphere, but also, to tackle more philosophical issues of female self-fulfillment and self-determination.

Writing by Canadian women in the 1960s and 1970s drew attention to the lives of girls and women, and perhaps no women of the period did so better than Nobel Prize-winning author Alice Munro. She discussed the politics of the domestic, and women’s hope for more freedom and control over their lives, in stories that draw loving attention to the complicated lives of seemingly ordinary, boring, women. For example, Munro’s short story cycle Lives of Girls and Women tells the coming of age story of Del Jordan. What is so remarkable about the story is that it details the conversations of small town women and the complexity of their relationships with each other.

One of the concerns about Canadian women’s authors in the 1960s and 1970s is that their work was not sufficiently literary. One of the ways that Canadian feminist literary critics responded to this charge was by addressing the specifically literary elements in their work. For example in Marjorie Garson’s article for Canadian Literature on Lives of Girls and Women, she notes that Del wants to make lists of all Real Life, including all of the people, and events in the town and how no list is ever complete (45–46). Epics tend to use lists, and list making, as a way of encompassing and describing vast and complex worlds. As Garson notes, lists are inevitably selective because they are “constituted by selectivity—by a prior act of classification that defines the set of objectives to be enumerated—and because it usually cannot contain the whole set” (46). Lists in literature imply power; getting to decide what is worthy of being listed, and in what order, is getting to decide what is and is not worthy of inclusion. Munro’s short stories try to enumerate the entirety of women’s lives and yet, like Del’s lists, they always come up short because the lives of girls and women are simply too rich to be captured exhaustively. However, what she shows is just how complex and interesting women’s lives in a small town actually are. Where so many authors before her has dismissed the lives of women like Del as being too uninteresting to write about, Munro’s short stories show that such lives are more than worthy of literary attention.

Works Cited

- Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. 1963. New York: W. W. Norton, 2001. Print.

- Garson, Marjorie.

I Would Try to Make Lists: The Catalogue in Lives of Girls and Women.

Canadian Literature 150 (1996): 45–63. Print. (PDF)

©

©