The Modernist Mode

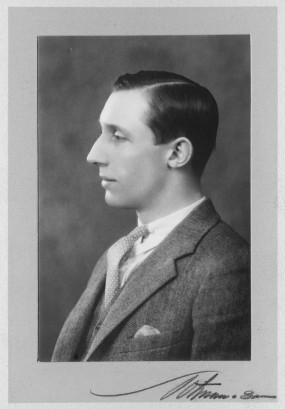

F.R. Scott (date / photographer unknown). Library and Archives Canada: accession no. 1995-115 NPC, e002282938.

The early decades of the twentieth century witnessed an explosion of Modernist works of art and literature in Canada, with the first instance of Canadian literary modernism, Arthur Stringer’s Open Water, appearing in 1914. In the late 1920s, a new generation of writers including A. J. M. Smith and F. R. Scott, Canadian poets and members of the Montreal Group, rejected the prevailing aesthetics and ideologies of earlier generations in favour of a new Modernist mode of writing. They advocated for harder, more mechanized styles of poetic expression (Moss and Sugars 1).

Modernist masculinization was a byproduct of the gender politics of the time. Male poets dominated Modernist poetics. Nevertheless, innovative writing by Canadian women writers such as Dorothy Livesay, P. K. Page, Margaret Avison, Miriam Waddington, Anne Marriot, and Anne Wilkinson emerged from the same Modernist tradition (Moss and Sugars 3; see also Irvine).

Dorothy Livesay receiving the Governor General’s award commemorating the Persons Case. Library and Archives Canada, 2003-02299-6.

Modernism marked an aesthetic, gendered, and generational divide within Canadian literature. Some poets considered Modernist poetics intrinsically masculine and tended to feminize earlier aesthetics. Laura Killian argues in “Poetry and the Modern Woman” that Modernism in Canada developed a structural misogyny through declarations and manifestoes which denigrated what was considered feminine or feminized language/writing/culture, and called for a new, hardened, vital, virile language and poetics (87). A. J. M Smith’s manifesto, “A Rejected Preface,” written in the mid-1930s but not published until three decades later in issue 24 of Canadian Literature (Spring 1965), affirms this poetic mentality through his denigration of what he terms “sentimental” (6) and “hyper-sensitive” (7) poetic expressions. Similarly, in 1928, he published “Wanted: Canadian Criticism” in Canadian Forum, in which he states: “Modernity and tradition alike demand that the contemporary artist who survives adolescence shall be an intellectual. Sensibility is no longer enough, intelligence is also required. Even in Canada” (qtd. in Moss and Sugars 1). Modernizing Canadian poetry meant removing sensibility as a primary marker of quality. Affect was to be secondary to formal exploration, and if Canadian women wanted to publish in Canada, Smith implies, they needed to do so in forms that imitated a hyper-masculine modern Canadian aesthetic.

Works Cited

- Irvine, Dean J. Editing Modernity: Women and Little-Magazine Cultures in Canada, 1916–1956. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2008. Print.

- Killian, Laura.

Poetry and the Modern Woman: P.K. Page and the Gender of Impersonality.

Canadian Literature 150 (1996): 86–105. Print. (PDF) - Smith, A. J. M.

A Rejected Preface.

Canadian Literature 24 (1965): 6–9. Print. (PDF) - Moss, Laura, and Cynthia Sugars. “Modernism: Introduction: Making It New in Canada.” Canadian Literature in English: Texts and Contexts, Volume II. Ed. Moss and Sugars. Toronto: Pearson, 2009. 1–26. Print.

©

©