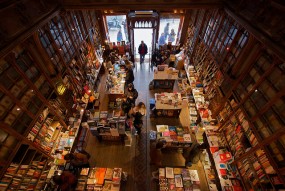

A bookstore. Natalia Romay, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, via Flickr.

Rethinking the Literary Field

Studies of literary prizes (Roberts), the economics of literature (English), and the hidden labour

of reading for pleasure (Shukin) are expanding the fields of literary studies. These scholars are among many academics that are rethinking the study of literature in a media-driven age. As Lorraine York notes in Literary Celebrity in Canada, in order to study literary celebrity she had to re-examine the kinds of knowledge about literature in Canada that was considered valuable:

In studying literary celebrity … the role of

publishing economicsis at the forefront, rather than shunted off to the side as unworthy of scholarly interest or value. … My files were full of academic articles from scholarly journals, references to books analysing their writing, and reviews. But in researching the topic of their celebrity I had to go back and retrieve those items that I had, first as a graduate student and then as a teacher of Canadian literature for twenty years, disregarded as not scholarly enough or simply irrelevant to what I saw as my primary literary purpose … (26–27)

These items included magazine profiles of writers, sales figures, and advertisements for books and film versions of books (27). A way to think about this change in perspective is to consider the way that a camera lens in a movie structures what viewers pay attention to. One perspective could be imagined as a close-up view of literature. In this view, scholars and students may take up the research methods of close reading or textual analysis to interpret particular passages or texts as a whole (for example, close readings of poems). But what happens when we pull back from this close-up view and we try to find a more panoramic, wide-angle view of Canadian literature? Here, scholars and students can engage research methods such as book history, material production, and reception studies to examine how institutional agents such as publishers, booksellers, and literary prize committees participate in the production and contestation of the value of Canadian literary works.

The study of the production of value complicates and enriches literary scholarship. One way of understanding the methodology of this guide is to focus on the key terms used in the title, Producing and Evaluating Canadian Texts.

- Why producing and not writing?

- Why evaluating and not reading?

- Why texts and not literature?

The choice to talk about producing rather than writing follows from the work of scholars such as Rachel Malik, who argues that the processes of producing and publishing texts precede[] writing and govern[] the possibilities of reading

(707). Publishing, therefore, is not merely a process of gatekeeping (where experts and editors select only what they perceive to be the best texts for publication) or mediation (where editors and producers work with writers to make changes to manuscripts before they are published for readers). The pre-existing structures of publication and book distribution affects what writers either react against or conform to in their work, what publishers accept, and what readers learn to prefer.

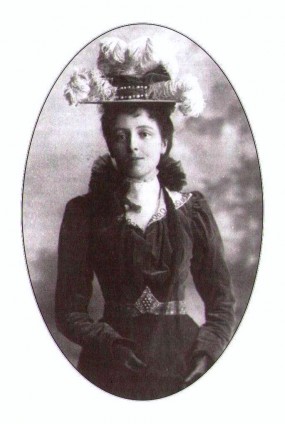

Lucy Maud Montgomery. By Anonymus [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

a continual processin operation through

a wide variety of individual activities and social and institutional practices(181). For Smith, texts,

like all other objects we engage with, bear the marks and signs of their prior valuing and evaluations by our fellow creaturesand are, therefore,

always to some extent pre-evaluated for us(182). By this she does not mean that readers do not value and evaluate texts; rather, what she means is that such acts by individual readers or communities of readers (for example in a literary event such as CBC’s Canada Reads) do not happen in isolation from other processes of evaluation, like editing, publication, marketing, recommendations, and adaptations into other media, like movies. The process of evaluation, moreover, can be historicized. By historicized, scholars mean that a concept (here, evaluation) can be placed into a historical context and by doing so we can better understand how that concept works. Just as works published today go through a continual process of evaluation, so too did early settler accounts of Canada such as Catharine Parr Traill’s The Backwoods of Canada or Susana Moodie’s Roughing It in the Bush, and iconic works of Canadian fiction like Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables.

William Gibson. David Alliet, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

Finally, the choice to discuss evaluating texts rather than evaluating literature has to do, in part, with the way that the concept of literature already contains value judgments. For example, consider the work of William Gibson. Gibson is perhaps best known for coining the term cyberspace, he pioneered the cyberpunk subgenre, and his debut novel, Neuromancer, won multiple awards (including the Nebula Award, the Philip K. Dick Award, and the Hugo Award). His works are well reviewed, and yet some critics may not take his work seriously as literature. In part, this depends on how his work is framed and marketed. Is Gibson a science fiction writer? Is he a speculative fiction writer? What kinds of assumptions about literary value are contained within each of these terms? But, it may be asked, if we want to avoid the value judgments that come with discussing literature why don’t we talk about books rather than talking about texts? What do scholars of literature mean when they talk about texts? As Leah Price notes, [o]n the first day of English class, freshmen learn that

(10). According to David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery, book historians distinguish between texts, books, and mediums (3). A text in this paradigm is a written document to be read that has a physical or digital form. Thus, when literary scholars say that they are studying texts rather than works of literature they are, to some extent, implying that the field can generate knowledge from a wide range of textual artifacts, like tweets, novels, short stories, and comic strips. A book, in contrast, is a physical object (2–3).book

is a dirty word: what they’re reading now needs now to be called a text.

This is more than a euphemism: one refers to a material object, the other to a sequence of words

Taking a wider-angle view of the production and contestation of the value of Canadian literary works requires scholars to consider texts, ideas, and processes that might at first seem outside the scope of a traditional English class. Canada’s culture of arts funding did not originate in a vacuum, and in order to understand where the Canadian publishing industry is today it is important to consider the history of book publishing in Canada. To begin this conversation, this chapter will discuss the Massey Report, a document that set the paradigm for arts funding in Canada after World War II, and the Canada Council, the main body responsible for funding the arts in Canada. From there we will turn to a discussion of some of the major figures that contribute to book production besides the author, such as publishers, literary agents, and editors. The chapter will end with an introduction to the study of literary celebrity.

Questions to Consider

- We noted earlier that the term literature has connotations of value. As a reader, have you encountered these value judgments before? For instance, have you ever been told to stop reading something because it wasn’t good for you? Have you ever dismissed a text as not worth reading? What implications do these judgments of what does and does not count as literature have on society? More specifically, how do they inform our perceptions of people who read texts that are deemed literary and those who read texts that are not?

- Above we suggest that the study of the process of producing texts, constructing literary value, or maintaining literary celebrity can produce valuable knowledge. If this is true, the issue becomes, how do we do this kind of study? What might be the objects of study? What might we learn by studying these processes or objects?

Works Cited

- English, James F. The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2008. Print.

- Finkelstein, David, and Alistair McCleery. An Introduction to Book History. New York: Routledge, 2005. Print.

- Malik, Rachel.

Horizons of the Publishable: Publishing in/as Literary Studies.

ELH 75.3 (2008): 707–35. Print. - Price, Leah.

Introduction: Reading Matter.

PMLA 121.1 (2006): 9–16. Print. - Roberts, Gillian. Prizing Literature: The Celebration and Circulation of National Culture. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2011. Print.

- Shukin, Nicole.

The Hidden Labour of Reading Pleasure.

ESC: English Studies in Canada 33.1 (2007): 23–27. Print. - Smith, Barbara Herrnstein.

Value/Evaluation.

Critical Terms for Literary Study. Ed. Frank Lentricchia and Thomas McLaughlin. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2010. 177–85. Print. - York, Lorraine. Literary Celebrity in Canada. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2007. Print.

©

©