1960s: The Decade of Social Change

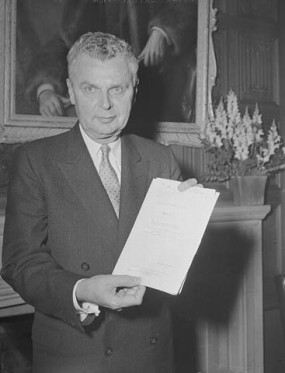

PM John Diefenbaker with Bill of Rights, 5 September 1958. Duncan Cameron / Library and Archives Canada: PA-112659

Several important political developments in the 1960s helped strengthen Indigenous nationalism in Canada. Until the 1960s, Status Indians—peoples legally recognized by the Indian Act—lacked many rights enjoyed by Canadian citizens, as the Indian Act categorized them as wards of the state (see Erin Hanson’s The Indian Act

). They gained the right to vote federally only in 1960 (1962 for the Inuit), after the enactment of the Canadian Bill of Rights (Lutz 168). Most residential schools were closed in the later 1960s, although the last school did not shut down until the late 1990s (see AANDC’s Indian Residential Schools

). Several Indigenous political organizations formed in the early 1960s still exist today under new names. Most prominent of these was the National Indian Brotherhood (1967), which was reformed in 1985 as the Assembly of First Nations.

In 1969, Jean Chrétien, then Minister of the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (DIAND), introduced the White Paper, a policy document that proposed to dissolve his department and abolish the Indian Act, unilaterally assimilating peoples covered by it. This act would have freed the government from all treaty promises and extinguish any notion of what came to be called Aboriginal rights (see The White Paper 1969

).

Reactions to the White Paper prompted a more critical voicing of Indigenous rights against the colonial infrastructure that sought assimilation over support. As Hartmut Lutz suggests, “the response to the White Paper helped encourage already existing tendencies towards Native cultural nationalism” (171–72). Harold Cardinal’s The Unjust Society (1969), “a seminal book for Native cultural nationalism” (172), responded to the rhetoric of the Canadian federal government by stating, “‘Indian people are now impatient with the verbal games that had been played’” (qtd. in Lutz 172). Cardinal hoped “‘to point a path to radical change that will admit the Indian with restored pride to his [sic] rightful place in the Canadian heritage … and find his place in Canadian society’” (qtd. in Lutz 172).

The 1960s were also an important decade for Indigenous writers in Canada, whose work became increasingly visible to the general public. Lutz summarizes the historical context of this era in his article Canadian Native Literature and the Sixties: A Historical and Bibliographical Survey

. As Lutz states,

By the end of the sixties Native people in Canada were no longer invisible or inaudible. Gradually … they started to articulate their demands and to express their cultural identity in writing, using English as the lingua franca of pan-Indian and intertribal communication, and as the appropriate medium to reach the Canadian majority at large. (174)

The DIAND summarized the aftermath of the White Paper in a 1986 report:

What the government had not fully understood was the value Indian people placed on their special status within confederation and on their treaty rights. The Indian Act thus revealed itself to be a paradox for Indian people. While it could be viewed as a mechanism for social control and assimilation, it was also the vehicle that confirmed the special status of Indians in Canada.

So vehement was the negative reaction of Indian people and the general public that the government withdrew the White Paper. Ironically, the new policy had served to fan sparks of Indian nationalism. (qtd. in Lutz 171)

Opposition to the White Paper brought Indigenous peoples from different nations and traditions together to protest inequalities and injustices. For example, the Union of BC Indian Chiefs was formed in 1969 to assert Indigenous title rights in British Columbia (The White Paper 1969

).

The events of the 1960s produced a strong movement of Indigenous political and cultural nationalism. As Lutz argues of Indigenous literature that emerged in the late 1960s, “[o]ften, poetry and prose fiction are direct results of a growing pride in Nativeness, and contents and message reflect the process of growing socio-political and cultural emancipation of Native people in Canada” (180).

Works Cited

- Lutz, Hartmut.

Canadian Native Literature and the Sixties: A Historical and Bibliographical Survey.

Canadian Literature 152–53 (1997): 167–91. Print. (PDF) - Hanson, Erin.

The Indian Act.

Indigenous Foundations. First Nations Studies Program at [the] U of British Columbia, 2009. Web. 15 Aug. 2013. (Link) - Canada. Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada.

Indian Residential Schools – Key Milestones.

28 Mar. 2012. Web. 19 Aug. 2013. (Link) The White Paper 1969.

Indigenous Foundations. First Nations Studies Program at [the] U of British Columbia, 2009. Web. 15 Aug. 2013. (Link)

©

©