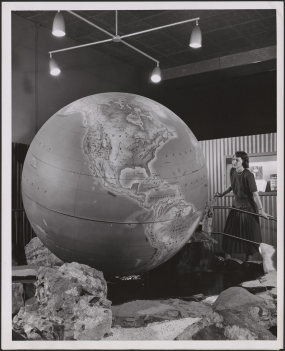

A visitor to the Royal Ontario Museum examines the Bickell Globe. Canada. Dept. of Manpower and Immigration, Library and Archives Canada: accession no. 1972-047 NPC, e011051719-v8.

In his “Conclusion to a Literary History of Canada,” Northrop Frye famously observes, “that Canadian sensibility … is less perplexed by the question ‘Who am I?’ than by some such riddle as ‘Where is here?’” (253). The question “where is here?” reflects the position of the explorer and the settler moving through unknown territories. Indigenous literatures respond to this question by asserting the voices and presence of peoples who are here already, familiar and connected with the land. The ways we connect to here, elsewhere, and the histories that inform our homes are all crucial to our identities and our positioning in relation to others.

This exercise helps you reflect on how you perceive your surroundings, your community, and yourself, thereby developing a better understanding of your positioning. This process will help you develop a more self-reflexive critical perspective.

Histories

- List regional, national, or even continental spaces that you consider important to your understanding of your personal, ethnic, and cultural origins across generations. Also, list other cultural heritages that have an impact on your sense of self, such as those of close friends or family.

- What does here mean to you? How do you consider yourself connected to your surroundings, and what words would you use to describe it? Consider how the previous list of heritages might inform these perspectives by providing alternative ideas about place. Also consider rural, suburban, and urban experiences to help open up possibilities for discussion.

- List words that you would use to describe your surroundings. What does your language reveal about your understanding of space and its uses? Are there particular words that spring to mind right away that indicate assumptions about or biases towards particular types of cultural and social engagement with different spaces?

Classrooms

- The classroom is not a neutral space, but rather a location where differences may be reinforced and negotiated. Practices, such as which texts are taught, how the details are discussed, and whose opinions are considered, can function either to maintain colonial assumptions, power dynamics, and values (such as essentialist understandings of authenticity), or to create an atmosphere of critical respect and alliance with Indigenous peoples that move beyond essentialism to dynamic interactions. Understanding one’s own positioning helps to mitigate against colonial assumptions and opens up dialogue.

- Discuss what personal differences and histories suggest about the social climate of the classroom. What do we need in order to function as a classroom community, to interact and work together in a productive way? What values must we share? Discuss these communal values, and different interpretations of them.

- Consider your answers to the questions about your personal history in relation to this broader perspective and an allied, respectful interaction with marginalized perspectives. How do essentialist ideas, such as those surrounding authenticity, fit into this perspective?

- What I Learned in Class Today, put together by the UBC First Nations Studies Program, provides further discussion topics and resources to improve discussions of cultural diversity in the classroom. It seeks to make classrooms safe and productive spaces for all students. It also offers powerful videos of Indigenous students discussing their experiences, illustrating the necessity of a careful, respectful, and articulate approach to cultural diversity in the classroom.

- Watch the video, then discuss a story that stood out to you. What did the person experience, and how did it affect them? How could the situation have been handled differently? How does the video impact your thoughts on the first question in this section?

Communities

Literatures reflect many social dynamics, especially those of the communities in which they participate. For many Indigenous peoples and their literatures in Canada, the non-Indigenous community plays a significant role in these social dynamics. Considering how communities are structured gives insight into the foundations of common ground as well as respect for difference, which is crucial to the critical perspective of an ally.

- What analogies can we draw between the needs within a respectful classroom and the needs of multicultural communities composed of immigrants and Indigenous peoples? It may be helpful to list variables and their functions that compose communities, such as national or municipal boundaries, governments and other power structures, as well as shared identifications such as ethnicity, to draw out these connections.

- How might these community structures, especially those established by non-Indigenous peoples, relate to and impact marginalized Indigenous peoples? Consider these challenges at different levels of community, from municipal to regional, to federal, to international levels.

- Thinking about such settler-Indigenous dynamics within particular spaces helps us develop ideas about what a common ground might be composed of. How do these challenges also relate to our multiple ways of knowing and understanding where we live, such as those discussed in the previous two sections?

Works Cited

- Frye, Northrop.

Conclusion to the First Edition of Literary History of Canada.

[1965]. Northrop Frye on Canada. Ed. David Staines and Jean O’Grady. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2003. 339–73. Google Books. Web. 13 Aug. 2013. - UBC First Nations Studies Program. What I Learned in Class Today: Aboriginal Issues in the Classroom. Faculty of Arts, U of British Columbia, n.d. Web. 11 Sept. 2013. (Link)

©

©