Respectful critical engagement with literary works necessitates being aware of our own assumptions tied to our social and cultural position, and to work across the boundaries that seem to divide different groups, knowledges, and experiences. Assumptions about differences often support essentialist thinking that reduces people and their experiences to stereotypes and singular characteristics.

Visualizing settler-Indigenous relations. One sign from Edgar Heap of Birds’ street sign public art project Native Hosts, 1991-2007. Collection of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, The University of British Columbia. Gift of the artist, 2007. Photograph by Alissa McArthur / Canadian Literature, 2013

Non-indigenous critics, and Indigenous critics from other cultural backgrounds than those they work with, can work as allies to affirm a diversity of Indigenous voices by engaging specifically with the cultural, social, political, and personal influences that particular authors draw on. This criticism seeks to better reflect the literary, cultural, and social work of a given author and text, and to engage in a knowledgeable dialogue with it. Without this self-critical engagement or positioning, critics run the risk of reverting to colonial stereotypes and ideas that sustain the oppression of the plurality of Indigenous voices rather than to affirm them.

Importantly, all these terms and considerations discussed here raise the question of who speaks for whom. For instance, some Indigenous people may self-identify as Indian—for any of a number of reasons, including to deliberately signal their construction under colonial law. However, for the majority of voices in the broader critical conversation, it is best to be aware of one’s position and to speak respectfully from it.

The Terms

The following list of terms addresses different usages and their historical significance. While we use the term Indigenous in this chapter, which terms should you use when speaking and writing about Indigenous peoples and literatures? To respect the peoples, cultures, and histories you engage with, use the terms that people prefer for themselves, and choose the most specific term if you know it. For example, Eden Robinson identifies herself specifically as a Haisla-Heiltsuk writer. Likewise, Mourning Dove (1882?–1936), while often discussed as a Native American writer because she was born and lived in the USA, in fact “always referred to herself as an Okanogan” (Brown 259), an Indigenous nation that spans the Canada-US border. The diversity of Indigenous heritages that inform these works is also why we refer to the group of texts in the plural as literatures.

As well, individuals do not always fit into the available social categories: labels can be problematic. In “Real” Indians and Others: Mixed-Blood Urban Native Peoples and Indigenous Nationhood, Bonita Lawrence discusses these issues in more depth, in particular the complex ways in which peoples of mixed Indigenous descent negotiate their identities in Canadian cities. Lawrence argues that, for some academics, Indigenous identity was understood as being counter to modernity and in terms of primordiality (1). In order to assert their Indigenous rights, Indigenous peoples are often literally put on trial to account for their supposed authentic Indigeneity or primordiality. Lawrence points out that in Canada, the Indian Act’s legislation of the definitions of Indigenous identity necessitates the policing of Indigenous identity by people in both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. This need to demarcate boundaries creates complex issues and conflicts, raising questions about the rights of peoples of mixed ancestry and fears of appropriation of Indigenous identity. As Lawrence argues,

The question of who is an Indian, which lurks beneath the surface of many of the issues that contemporary Native communities are struggling with, is much larger than that of personal or even group identity—it goes directly to the heart of the colonization process and to the genocidal policies of settler governments across the Americas toward Indigenous peoples. (16)

Lawrence aims to understand how Indigenous peoples of mixed descent living in the city, away from reserves, complicates the legislated and discursive boundaries of Indigenous identity.

Finally, it is important to note that there is no right or wrong way for individuals to identify themselves. The terminology an Indigenous person uses to describe herself is a personal choice that can carry important political implications. As Lawrence states, “identity … is far more complex than any neat categories can suggest” (11).

-

Indigenous

In this introduction to Indigenous literatures in Canada, we use the general term Indigenous to signify all peoples who acknowledge racial, ethnic, and cultural origins or roots from Turtle Island (an Indigenous term for what settler society calls North America) prior to European contact and colonization. Other terms reflect a less inclusive understanding of Indigenous peoples, including the more popular Canadian term First Nations discussed below. In particular, in Canada a term like Indian can reflect an imposed legal definition. At the same time, as Thomas King reminds us, “the fact of the matter is that there has never been a good collective noun because there never was a collective to begin with” (4).

-

Métis

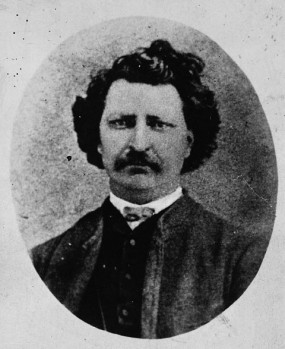

Métis leader Louis Riel. Louis D. Riel. ca. 1879 – 1885. Duffin and Co. / Library and Archives Canada, accession no. 1973-001 NPC, C-052177.

This is a contested term. Due to their mixed ancestry, the Métis are a more difficult group to legally and culturally define. Historically, they were mistreated and referred to by the derogatory term half-breed. The cultural group we are talking about, as the spelling of the name implies, is largely grounded in early French and Scottish settlements in what is now Manitoba. The Supreme Court decision R. vs. Powley (1982) clarified that “‘Métis’ refers to distinctive peoples of mixed ancestry who developed their own customs, practices, traditions and recognizable group identities separate from their Indian, Inuit and European ancestors.” It goes on to emphasize that this term does not, therefore, just “refer to all individuals of mixed Aboriginal and European ancestry” ( n. pag.), as it once did, and for some, still does. Thus, now the Métis are legally considered a specific, unique cultural group that share Indigenous rights with the First Nations and Inuit of Canada.

Historically, the Métis have claimed that they are owed land in the territory now known as Manitoba because a land claim was part of the original agreement that ended the Red River resistance. In 2013, a historic Supreme Court judgment ruled that the Canadian government did not follow through on their agreement to give land to Manitoba Métis after the Red River resistance in 1870. In the Manitoba Act (1870, s. 31), the government promised to set aside 1.4 million acres of land for the families of the Métis.

-

Aboriginal and First Nations

Constitution, 1982 commemorative stamp. Canada Post Corporation, Library and Archives Canada: accession no. 1989-565 CPA.

Aboriginal, an umbrella term devised for use in the Constitution Act (1982), states that “‘aboriginal peoples of Canada’ includes the Indian, Inuit, and Métis peoples of Canada” (pt. 2, sec. 35[2]).

First Nations is commonly used in Canada when referring to Indigenous peoples, replacing older terms such as Indian and Native. Although First Nations is not a government term, it is often used to mean Status Indian, since it reflects their national representative body, the Assembly of First Nations (1982–present), which includes neither the Inuit nor the Métis.

-

Inuit and Inuvialuit (formerly Eskimo)

Noonesweetik in his kayak, east of Dorset, June 1924. L.T. Burwash, Library and Archives Canada: PA-099100

Inuktitut is the most common language of the Inuit peoples across the Arctic, and one of the official languages of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. In Inuktitut, Inuit means people. Indigenous people from the Mackenzie delta in the western Arctic call themselves the Inuvialuit. Inuit replaced Eskimo as a term in Canada in the 1970s. A disputed etymology suggests that the term may have pejorative roots in the Cree language. To avoid this possibility, contemporary critics use Inuit to reflect the term that the Inuit peoples use for themselves.

Older Terms

Scholars and writers sometimes use the older terms Indian, Eskimo, and Native (as in Parker Duchemin’s work on Mackenzie), either because these reflect the general terms used during the writer’s or scholar’s time-period, or to emphasize the derogatory nature of the term in question. Writers and critics should be aware of the history and assumptions which accompany their language choices.

-

Indian and Native

Indian is an umbrella term, imposed by Europeans upon diverse groups of Indigenous peoples after contact, which erases the cultural diversity of Indigenous peoples. The term Indian in particular still carries legal weight. Consider the expression Status Indians, that is, those recognized as Indian under the Indian Act (1876; 1985). The Indian Act was designed, in part, to limit the people who could claim to be a status Indians; many Indigenous women who married white men found that they lost status, as did their children and their children’s children.

Furthermore, many people who are not Status Indians have reasserted Indigenous ancestry; this legal framework, though, negatively defines them as non-status Indians, implying that Status Indians are somehow real Indians while non-status Indians are lesser in some way. While used commonly in the past, critics now consider the terms Indian and Native problematic and outdated. For this reason, the former terms often appear in older issues of the journal, Canadian Literature, but rarely in newer issues.

Further Reading

As you can see, most of these terms have undergone significant revisions over time, and in all likelihood, these terms will continue to shift in the coming decades. These changes reflect attempts to develop a culture of respect for Indigenous peoples in Canada. UBC’s Indigenous Foundations website has more detailed discussions on the complex histories of these terms and Indigenous identity.

Works Cited

- Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada.

Powley–Frequently Asked Questions.

Métis Rights Management. 15 Sept. 2010. Web. 13 Aug. 2012. (Link) - Duchemin, Parker.

Canadian Literature 124–25 (1990): 49–74. Print. (PDF)A Parcel of Whelps

: Alexander MacKenzie among the Indians. - Lawrence, Bonita.

Real

Indians and Others: Mixed-blood Urban Natives and Indigenous Nationhood. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 2004. Print. - Canada. Dept. of Justice. Constitution Acts, 1867 to 1982. Justice Laws Website, 29 July 2013. Web. 17 Sept. 2013. (Link)

- Indigenous Foundations. First Nations Studies Program, U of British Columbia. 2009. Web. (Link)

- King, Thomas. The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America. Toronto: Anchor Canada, 2013. Print.

- Manitoba Act (1870) [An Act to amend and continue the Act 32 and 33 Victoria chapter 3; and to establish and provide for the Government of the Province of Manitoba]. Parliament of Canada. Site for Language Management in Canada (SLMC). Official Languages and Bilingualism Institute, U of Ottawa. n.d. Web. 18 Sept 2013. (Link)

- Supreme Court of Canada.

Manitoba Metis Federation Inc. v. Canada (Attorney General), 8 March 2013.

Supreme Court Judgements. Lexum collection. 13 Sept 2013. Web. 18 Sept 2013. (Link)

©

©