The introduction to Daniel David Moses and Terry Goldie’s An Anthology of Canadian Native Literature in English begins with this assertion:

We were concerned as we discussed an appropriate introduction for this book not to conceal the differences between our perspectives as a Native writer and a white academic. The process of selecting an anthology is like a long discussion and, in keeping with a body of work so rooted in the oral tradition, we decided a dialogue would be the best format. (xix)

This statement reflects Moses and Goldie’s awareness of their position as critics. By acknowledging their different perspectives, they show awareness that their criticism is influenced by the mixture of differences based in power, education, racialization, and culture, among other things.

Positioning signals an important tension in literary criticism between the reader and the content of the literary work; between readers’ background and how they perceive the texts. It is a problem that calls for self-awareness and sensitivity.

How do we recognize our own positions?

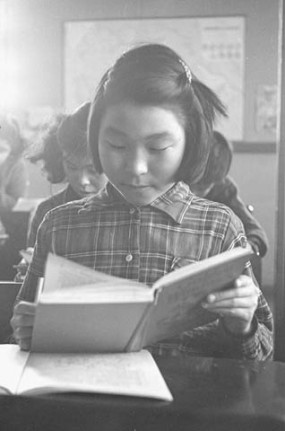

The way we interpret a work is influenced by our backgrounds. “Innu(?) girl reading from a schoolbook. by Richard Harrington. Library and Archives Canada, accession number 1976-086 NPC, PA-146598

It’s easy to assume that other readers understand a work in the same way that we do. But reading is a subjective act, and interpretation varies between individuals.

Readers’ backgrounds influence the way they read. The words are interpreted through their relationship with each individual’s unique understanding of language and personal experiences. Recognizing the limitations of our experiences and how these inform our perceptions of a text is an important part of developing critical self-awareness.

As Thomas King reinterates throughout The Truth About Stories, the importance of stories is that we hear them. To be able to hear, we need to try to side-step our biases and preconceptions about the world. As W. H. New asserts in an editorial on Indigenous literatures, “no one who does not listen learns to hear.” (4)

Literature often foregrounds our differences as much as our similarities, and asks us to engage with these carefully, instead of relying on stereotypes and assumptions. A critic’s work is to navigate around false assumptions to see people as complex individuals rather than representations of groups.

By being self-aware of how our personal experiences and cultural and social histories contribute to our perceptions, we can start to engage responsibly and critically as readers of literature.

Works Cited

- King, Thomas. The Truth about Stories: A Native Narrative. Toronto: Anansi, 2003. Print.

- Moses, Daniel David, and Terry Goldie, eds. An Anthology of Canadian Native Literature in English. 3rd ed. Toronto: Oxford UP, 1998. Print.

- New, W. H.

Learning to Listen.

Editorial. Canadian Literature 124–25 (1990): 4–8. Print. (PDF)

©

©