George Copway (1818–1869; Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh) was an Ojibwa (Anishinaabeg) writer, lecturer, Methodist missionary, and an important early Indigenous literary figure. Copway’s autobiography, The Life, History, and Travels of Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh (1847), is said to be the first book written and published by an Indigenous person in North America. Life, Travels, and History details Copway’s conversion to Christianity at the age of twelve and life in the Ojibwa community before and after contact with European settlers. It quickly became a bestseller, with six reprintings in its first year (Smith n. pag.). As Laura Moss and Cynthia Sugars note, Life, History, and Travels “blends communal history and personal experience as it incorporates traditions from oral storytelling and missionary tale-telling” (240).

Rice Lake and Onotabee River, 1907. Roy Studio/Canada. Patent and Copyright Office, Library and Archives Canada: PA-029202

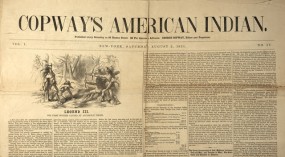

Copway’s family belonged to the Mississauga band of the Ojibwa whose territory stretched north of Cobourg, Ontario, around the Rice Lake area. In 1850, Copway published an account of Ojibwa culture and traditions, Traditional History and Characteristic Sketches of the Ojibwa Nation, in which he advocated for a permanent territory for Indigenous peoples. Copway founded his own weekly newspaper in 1851, Copway’s American Indian, with support from prominent scholars and literary figures. However, despite contributions from famous contemporary writers such as John Richardson, the newspaper folded after three months. Although Copway initially enjoyed success as a literary celebrity, he fell out of favour in the 1850s and struggled with financial difficulties. As W. H. New notes, “[l]iterary histories still tend to overlook as literature the extensive work of Native writers … [such as] … Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh (George Copway)” (5, emphasis in original).

Copway and Politics

Copway’s writings reflect his political views about the displacement of Indigenous peoples from their traditional lands. He introduces his Traditional History and Characteristic Sketches of the Ojibway Nation with the hope that,

In thus giving a sketch of my nation’s history, describing its home, its country and its peculiarities and in narrating its traditionary legends I may awaken in the American heart a deeper feeling for the race of red-men and induce the pale-face to use greater effort to effect an improvement in their social and political relations. (vii)

In Life, History, and Travels Copway also recounts the sale of much of the Mississauga’s traditional territory in the year of his birth. In particular, he notes the difference between what was signed and what was said concerning the islands in the lake:

They [those who made the agreement on behalf of the Anishinaabeg] were repeatedly told by those who purchased for the government, that the islands were not included in the articles of agreement. But since that time, some of us have learned to read, and to our utter astonishment, and to the everlasting disgrace of that pseudo christian nation, we find that we have been most grossly abused, deceived, and cheated. Appeals have been frequently made, but all in vain. (Life, History, and Travels 66, emphasis in original)

Although Traditional History was also a bestseller in its time, Copway’s political views countered the widespread opinion that Canada had treated Indigenous people justly.

Questions about Copway’s Authorship

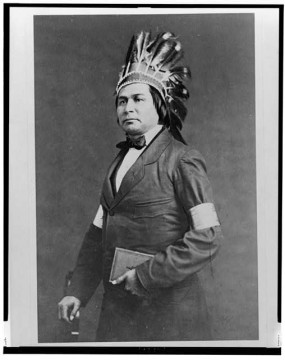

Portrait of Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh, George Copway, ca. 1860. Library of Congress, Washington, DC: LC-USZ62-121977, cph 3c21977.

Despite his prolific output, Copway has not received nearly as much scholarly attention as another early Indigenous writer, E. Pauline Johnson. As well, biographers have questioned his authorship. For example, in Copway’s entry in The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature, Penny Petrone notes, “[n]o one can be certain whether or not Copway’s educated wife collaborated in the writing of his books” (234).

- What does it mean to question the authenticity of an author’s published work?

- How might Copway’s Christianity and his work as a Methodist missionary affect the reception of his work? Consider why Indigenous peoples who converted to Christianity might not considered authentically Indigenous.

- Compare Donald B. Smith’s short biography of Copway in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography to A. LaVonne Brown Ruoff’s author entry in The Heath Anthology of American Literature and this anonymously written entry in Early Native American Literature.

- Which of these accounts is most sympathetic to Copway’s frequent financial difficulties? How do they portray his hardships and what is implied by these descriptions?

- Which leaves the strongest impression that Copway was unreliable? Why might it be important to consider that witnesses to history can be unreliable? What does this say about Copway’s travel writings and historical accounts in general, as well as about received notions of history and the historical biographer’s position toward her subject?

Works Cited

- Copway, George. The Life, History, and Travels of Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh. Albany: Weed and Parsons, 1847. Open Library. Web. 21 May 2012. (Link)

- Ruoff, A. LaVonne Brown.

George Copway.

Author pages. The Heath Anthology of American Literature. 5th ed. Ed. Paul Lauter. Web. 18 Dec. 2012. (Link) - Smith, Donald B.

KAHGEGAGAHBOWH (Kahkakakahbowh, Kakikekapo) (known as George Copway).

Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Web. 18 Dec. 2012. (Link) - Copway, George. Traditional History and Characteristic Sketches of the Ojibway Nation. 1851. American Libraries Internet Archive. Web. 31 May 2012. (Link)

- Petrone, Penny. “George Copway.” The Oxford Compasion to Canadian Literature. 2nd ed. Toronto: Oxford UP, 1997. 233–34. Print.

- Moss, Laura, and Cynthia Sugars. “George Copway (Kah-ge-ge-geh-bowh).” Canadian Literature in English: Texts and Contexts. Vol. 1. Toronto: Pearson, 2009. 239–40. Print.

©

©