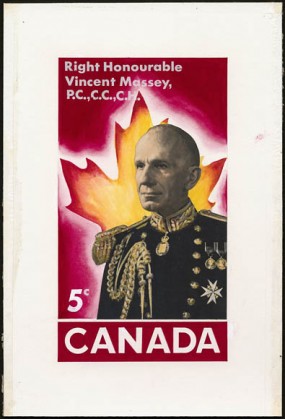

A stamp featuring Vincent Massey. Library and Archives Canada / Canada Post, e003576162, 1989-565 CPA

In order to think through how literary value is produced in Canada, we look back at how and why some key institutions that facilitate cultural production were formed. To address this national concern, the Canadian government appointed a task force, or Royal Commission, that was empowered to call witnesses, acquire information, and to write up a report for the government with suggestions about how to develop and support Canadian culture. The Royal Commission on the Development of Arts and Letters (est. 1949) is more commonly called the Massey Commission in homage to its chairman, Vincent Massey (1887–1967). It had a massive impact on the way culture is produced in Canada. The commission released a report in 1951, known as the Massey Report, which made recommendations that led to the development of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), the creation of the National Library, and the establishment of the Canada Council for the Arts, a body that supports and funds artists in Canada and administers awards like the Governor General’s Awards.

Culture and Nation Building

The Massey Report concluded that the government should play a role in developing art, culture, and universities in Canada. A key word in the title of the Commission is development. The Commission studied the “National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences” in Canada. The underlying ideology of the report was that Canada did not yet have a national culture that was as valuable as the national cultures of France and England, or one that could withstand the influence of American culture. Such a culture would need to be developed, and doing so would be a project of national import for Canada’s cultural independence. Establishing a national literature was important, at least in part, because in the Commission’s view, it was “the greatest of all forces making for national unity” (225; ch. 15, par. 12). To have this unity, however, the authors of the Massey Report suggests that Canadian writers would first have to find their “centre of gravity” while enduring the strong influences of literature from England and France (225; ch. 15, par. 12). The report continues, detailing how it was also necessary to defend Canadian literature and writers from “the deluge of the less worthy American publications” since they “threaten our national values, corrupt our literary taste[,] and endanger the livelihood of our writers” (225; ch. 15, par. 13). American culture was seen as a popular mass culture that did not contribute to a national moral and cultural uplift, and a key concern of the report was guarding against the potentially corrosive effects of American popular culture on Canadian writers and an emerging Canadian literary public. According to this line of thinking, developing a national culture was essential if Canada was to develop into a mature and culturally independent nation. For the Massey Commission, the value of cultural production, and therefore of literary production, was the power of culture to build a nation.

Stephen Greenblatt. By Bachrach. Evenfiel at en.wikipedia [CC-BY-SA-3.0], from Wikimedia Commons

Art, according to Greenblatt, is “an important agent then in the transmission of culture” (228). Creating a national culture, in this sense, was an important nation-building project for the Massey Commission because the resulting art was to collectively produce a cohesive notion of what it meant to be Canadian and in the process induct new Canadians into this imagined collectivity. In its discussion of literature, the Massey Report begins by suggesting “Canada has not yet established a national literature” but that progress was being made (225; ch. 15, par. 11). While the question of the existence of Canadian literature may seem odd, in the introduction to the re-release of her influential thematic study of Canadian literature, Survival, Margaret Atwood says she would regularly get two questions from audiences when she was on book tours in the 1960s. They wanted to know if there was a Canadian literature and, supposing there was one, they wanted to know if it was just a second-rate English or American literature (xvii). Note the value judgment Atwood captures here: the questioners ask if texts written by Canadians “counted” as literature. Importantly, the notion of a unified Canadian culture envisioned in the Massey Report has been contested by critics who see the vision of Canada in the report as quite limited. For more on these debates, see “Multiculturalism” and “Contesting Multiculturalism.” Here, then, we can see the role that the Massey Report and the institutions that arose from it played in socially constructing the value of Canadian literature—and in the process defining what kind of literature would “count” as contributing to that national literature.

The Massey Report and Publishing

The Massey Report treated a wide range of issues; for our purposes here, what matters is the way it allows us to see how the value of a national literature was an active social construction. Interestingly, the report seems to separate the concerns of publishers from those of writers. Returning to Rachel Malik, she observes that “[i]n a variety of discourses,”—and here we would include that of the Massey Report—“publishing is nearly always conceived either as a synonym for commercial interest, a mediating figure between writer and reader, a process of cultural gatekeeping, or as some combination of these” (710). But she contends that publication is composed of processes that include writing, editing, marketing, book design, etc. From this view, writing and publishing are intricately intertwined and cannot be treated as separate concerns, which is what the Commission set out to do.

Where the recommendations for writers focused on providing them with sufficient time to write, the influence of French and English writing traditions on Canadian authors, and funding, the recommendations for publishers focused far more on the Canadian bookselling marketplace. Canadian book publishing was defined by its financial insecurity and its size. In 1947, Britain published 1,723 works of fiction, the United States published 1,307, and English Canada published only 34 (228; ch. 15, par. 3). The Massey Report implied that writers were not producing enough high-quality fiction and publishers were struggling to distribute what they did publish across Canada’s great distances (229; ch. 15, par. 4). The report does note, however, that Canadian book publishers were trying to stimulate the market, including by the creation of book clubs and national awards (230; ch. 15, par. 10). In large part, however, the major recommendation of the report was that the Canadian book market was simply too small to allow Canadian publishers to compete with the much larger American publishers. The Canadian book industry needed to be protected. Cultural protectionism refers to rules in Canadian publishing that limit the ability of American publishers to work in Canada. To some degree, this cultural protectionism has worked. As Josée Vincent and Eli MacLaren show in their Canadian Literature article “Book Policies and Copyright in Canada and Quebec: Defending National Cultures,” in 2006 Canadian books accounted for 54% of sales of the book market in Canada (64–65).

While the Massey Report separates writing from publishing, what it implies is that the needs of writers and publishers are symbiotic but distinct. Canadian writers need time, space, and opportunity to produce texts; Canadian publishers need texts written by Canadians that will excite the Canadian reading public if they are to have a sustainable business. The Canada Council’s current granting system seems to support this view: although the council awards separate grants to writers and publishers, the two groups rely on each other. For example, in order for writers to be eligible to apply for a grant, they must already either have one book published by a professional publishing house or have pieces published in magazines. This is where small magazines are important, because they provide a venue for emerging writers to publish short stories and poems. However, many literary magazines in Canada rely on Canada Council grants themselves, and they need fresh Canadian writing in order to sustain their publications. Knowing this, writers tailor their work to the magazines they submit to. Therefore, although the Massey Report appeared to separate writing from publishing, the resulting system of producing Canadian texts demonstrates how the relationship is not a simple process where a text moves from writer to publisher, but a more complex one where the writer takes the requirements of potential publishers into account and the publisher in turn edits the writing to fit its conception of its audience, and so on.

Questions to Consider

- As a cultural consumer, do you pay attention to where the material you consume comes from? Do you spend money and time on art produced by Canadians? Why or why not? Where does the culture that you consume come from? Does this vary for different types of art (e.g., film, television, literature, online videos)?

- Do you think that the federal government should continue to play a role in financially supporting literature in Canada? If so, how would you justify having ttaxpayers support publishers and writers even if they don’t read these Canadian works? If not, how can publishers and writers remain financially viable, given the competition from US, UK, and French producers, whose larger populations mean that they enjoy economies of scale?

Works Cited

- Atwood, Margaret.

Introduction.

Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature. Toronto: Anansi, 2012. xv–xxv. Web. (Link) - Canada. The Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences 1949–1951. Ottawa: Edmond Cloutier, 1951. Web. 13 Apr. 2014. (Link)

- Greenblatt, Stephen.

Culture.

Critical Terms for Literary Study. Ed. Frank Lentricchia and Thomas McLaughlin. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2010. 225–32. Print. - Malik, Rachel.

Horizons of the Publishable: Publishing in/as Literary Studies.

ELH 75.3 (2008): 707–35. Print. - Vincent, Josée and Eli MacLaren.

Book Policies and Copyright in Canada and Quebec: Defending National Cultures.

Canadian Literature 204 (2010): 63–82. Print.

©

©