Styling Stories

- Serialization: Daniel Burgoyne’s Broadview edition of A Strange Manuscript is broken up into installments, maintaining the structure of its original serial form. How does this impact they way you read it as a single novel?

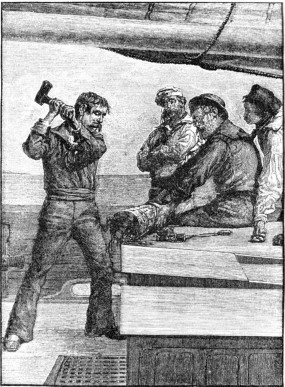

Gilbert Gaul’s first illustration for De Mille’s story. Harper’s Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, published on 7 January1888 (Volume 32, Issues 1620)

- History: On the first page of the novel, De Mille explicitly states the date the men on the yacht find the copper cylinder: 15 February 1850. How might contemporary readers have reacted to that date? What effect does having a specific date have on the veracity of the novel?

- Illustrations: An illustration by Gilbert Gaul accompanied each serialized installment of the story. These are reprinted in the Broadview edition. How do the images impact the reading?

- Science, Society, and Literature: The story is composed of interweaving narratives of exploration and discovery and theoretical musings on new information about the Antarctic, dinosaurs, and etymology. What is the significance of blending a contemporary adventure narrative with this other information?

Layering Stories

- Boredom: The story begins and ends with the bored yachtsmen. In

Colonialist Discourse, Lord Featherstone’s Yawn and the Significance of the Denouement,

Stephen Milnes notes that “[t]he first narrative frame is remarkable for its air of lassitude and indifference…. Listlessness and inertia prevail” (90). How is this emotional framing significant?- Why are the yachtsmen bored? What excites or agitates them? How does their boredom reflect their social position and values? What kind of comment might De Mille be making on their social standing and class privilege?

- Irony: Note how irony emerges from the interactions between the frame narrative of the becalmed yachtsmen and the narrative in the cylinder. Give examples, and explain what is ironic about the juxtapositions.

- More’s European heritage works to bind the two narrative spheres together. How does More’s unreliability as a narrator cast doubt upon other social values presented in the story? How do the heated conversations of the yachtsmen over the manuscript reflect their understandings of both More and themselves?

- Gothic utopia: Gerry Turcotte places this novel in the Canadian Gothic tradition, as it shows how “fear of the familiar can come to surpass that of the unfamiliar” (qtd. in Burgoyne n. pag.). What in this story slips between familiarity and unfamiliarity, between connection and revulsion? What does this accomplish?

- Satire: In

Strange to Strangers Only,

M. G. Parks notes that satire in the novel “works in two directions simultaneously, and depends just as much upon the inadequacy and extremism of Adam as upon those qualities in the Kosekin” (74). What is being satirized and why? - Morality: Judeo-Christian morality is presented in More’s story, and discussed by the yachtsmen in the frame narrative. What is the effect of the interaction between the novel’s gothic motifs and discussions about morality? See Parks on De Mille’s religious beliefs and how they might have influenced the content of the novel.

- Satire: In

Characterization

- The Critics’ Circle: The four men on the yacht act as critics of the strange manuscript, drawing on various areas of expertise to examine More’s story. What do their positions regarding the text reveal about their own biases and understandings of the world?

- Choose a specific critic and look at his contributions. What does he focus on in More’s story? How do his views contrast with the others? Look carefully, in particular, at chapter 26, which involves a heated discussion of the story’s literary merits.

- Heroic Foils: How do More and Agnew act as foils to popular notions of the heroic, white, male explorer? For example, they succeed in foraging in the Antarctic, but at the same time are completely incapable of controlling their movements on the sea.

- Love: The novel cycles around different definitions of love, binding marital and celestial ideals, and contrasting British and Kosekin notions of love in daily and marital life. Focus on specific expressions of love, such as Adam and Almah’s love for each other, Layleh’s infatuations with More, or Kohen Gadol’s interest in Almah. How do these different examples explore the roles of love? In what ways are they also being satirized?

Social and Political Readings

- Endings: The novel’s abrupt ending is, as Stephen Milnes notes, “an obtrusive structural problem that all readers have to wrestle with” (86). What are the final words of the frame characters? What do you think of the endings of both More’s narrative and the novel as a whole? Are they successful ways of concluding the parallel stories?

- Writing time: We are still left with questions: where and when did More gain access to papyrus to write on? When did More write his narrative and place it in the sea? What happened to Layleh and Kohen Gadol?

- Interruptions: Is the novel incomplete? Or is it purposefully interrupted by Featherstone’s unease at identifying with More, as suggested by Flavio Multineddu in his article

A Tendentious Game With An Uncanny Riddle

(64)? Why is it important which interpretation of the ending you take?

- Historical Determinism: The yachtsmen regularly attempt to connect knowledge from their time to judge the veracity of More’s story. The men posit that the setting of More’s narrative and its people seem to be a holdover from ancient times, deriving a sense of origins from studies in paleontology and etymology. How does the novel present these ideas? Take note especially the discussion of linguistic origins in Hebrew and Troglodyte history (especially 250–51 and 254–55).

- Rationalism and Colonial Perspectives: Colonial thinking—often under the guise of European rationality—was predicated on the belief that Indigenous peoples were primal, savage, and in need of civilizing. Does De Mille challenge such thinking or reinforce it? How does this story open up questions about the rigid definitions of culture and humanity? In what ways does the novel reflect racializing views of civility and savagery?

- Take note of the Judeo-Christian themes that weave throughout this narrative, beginning with the naming of the protagonist Adam (the first “man”). In what ways might Adam be considered a missionary to the Kosekin people? How successful or unsuccessful is he in this assimilationist process?

- Satirical cannibalism: One central ritual of the Kosekin society is human sacrifice and cannibalism. What role does cannibalism serve in Kosekin society? Is this just a stereotypical image of savage barbarity from De Mille’s time, or does it serve a richer purpose in the narrative?

- Can you see this religious rite as an act to parody Christian practices of Communion, in which believers ingest the body of Christ in the form of sacramental bread?

- Power: The Kosekin view of wealth, life, and power is completely opposite to that of the Europeans in the boat. How does the Kosekin perspective make the reader reconsider core values? What does this satirical approach say about ideas of progress, individualism, and hierarchy?

Works Cited

- De Mille, James. A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder. Ed. Daniel Burgoyne. Peterborough: Broadview, 2011. Print.

- Lamont-Stewart, Linda.

Rescued by Postmodernism: The Escalating Value of James De Mille’s

Canadian Literature 145 (1995): 21–36. Print. (PDF)A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder

. - Milnes, Stephen.

Colonialist Discourse, Lord Featherstone’s Yawn and the Significance of the Denouement in

Canadian Literature 145 (1995): 86–104. Print. (PDF)A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder.

- Multineddu, Flavio.

A Tendentious Game with an Uncanny Riddle:

Canadian Literature 145 (1995): 62–81. Print. (PDF)A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder.

- Parks, M. G.

Strange to Strangers Only.

Canadian Literature 70 (1976): 61–78. Print. (PDF) - Burgoyne, Daniel.

Peripheries of Fear.

Rev. of Peripheral Fear: Transformations of the Gothic in Canadian and Australian Fiction, by Gerry Turcotte. canlit.ca. 17 June 2012. Web. 25 Oct. 2012. (Link)

©

©