1990 marks a milestone in Indigenous literary history in Canada. Since 1990, the availability of Indigenous writings has steadily grown, indicated in part by the increasing diversity represented within anthologies by Thomas King (1990), Joel Maki (1995), Daniel David Moses and Terry Goldie (multiple editions: 1992; 1998; 2005; 2013 with Armand Garnet Ruffo), and Jeannette C. Armstrong and Lally Grauer (2001), among others.

Along with the growth in publications, in 1990, Okanagan writer Jeannette C. Armstrong also founded the literary journal Gatherings. This Indigenous-dedicated journal—tied to her ongoing activities to support Indigenous writers through the En’owkin Centre (est. 1982)—expanded this previously underdeveloped facet of the publishing community.

1990 also marks a milestone year in Indigenous literary criticism. That year, Penny Petrone’s early literary history Native Literature in Canada: From the Oral Tradition to the Present gave the field a scholarly foundation. In the same year, Canadian Literature published Native Writers and Canadian Writing, a special double issue dedicated to Indigenous writers and writing in Canada.

In his editorial for that issue, W. H. New reflects,

the time is not so distant when the Native was a conventional figure in Canadian literature—but not a voice (or a figure allowed separate voices). If Native characters spoke, they spoke in archaisms or without articles, in the sham eloquence of florid romance or the muted syllables of deprivation…. The model confirmed expectations. It nevertheless left the reality unquestioned, and therefore unmet. (4–5)

1990 marked a significant turning point in criticism, as more and more of it continued to focus on Indigenous writers and their works. In 1995, Canadian Literature published its Native, Individual, State issue, shifting focus to contemporary Indigenous relationships with land and state. In 1999, a special double issue on Thomas King further reflects this shift, offering one of the first volumes focused on an individual Indigenous author.

Oka

The First Nations Writing (2000) issue of Canadian Literature begins with the following, subtly cautionary remark, from the editor:

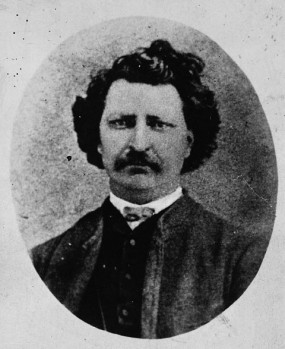

Louis Riel “Louis D. Riel.” ca. 1879 – 1885. Duffin and Co. / Library and Archives Canada, accession no. 1973-001 NPC, C-052177.

Many of the works discussed are autobiographical or deal with the ways Native lives are “read” by the mainstream culture. Louis Riel’s self-description as un néant, a ghost, reflects how he was and still is deployed as symbol more than remembered as a man. Like Oka, any incident to do with Aboriginal peoples that sparks conflict between what were once called “the two founding races,” the French and the English, is read not for what it might say about the aspirations, desires, or political demands of the Aboriginal people involved, but for what it says about relations between the two solitudes. Attention is paid, but for the wrong reasons, and in the end, the Aboriginal protagonists go to jail, or worse, and the mainstream media forgets the whole subject. Did we ever find out what happened to that golf course? (Fee 5)

This commentary foregrounds the importance of moving beyond colonial histories and interests, of recognizing alternative perspectives on Canada, and the many unacknowledged nations struggling for recognition and sovereignty within it.

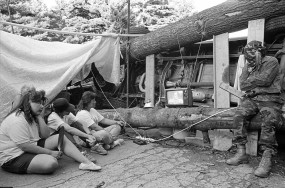

Canadian military and Quebec police personnel at the Oka stand-off, 3 September 1990. Samuel Freli via Wikimedia Commons

Interestingly, Fee cites 1990 as a point of reference, through the widely publicized Oka Crisis. In that land dispute, the town of Oka, Quebec proposed the redevelopment of a sacred grove and burial site into a golf course, prompting the Mohawk community of Kanesatake to barricade access to the site. On 11 July, the Quebec police responded with force that resulted in the death of one police officer, but failed to break the barricade. The conflict expanded regionally, and escalated over the next seventy-eight days to include the presence of the RCMP and the Canadian Army.

Mohawks watching Oka crisis news on barricades. 28 August 1990. Kanesetake, Quebec. Benoît Aquin, Library and Archives Canada: e010950700-v8

While Fee observes that “[a]ttention is paid, but for the wrong reasons” (5) by the media, the series of events at Oka nonetheless galvanized many Indigenous communities in solidarity against government threats to land and cultural rights. As one among many instances of Indigenous resistance (see Hill), the widely publicized conflict promoted the growth of Native nationalism in the Mohawk Nation (see Alfred) and inspired other communities as well. Thus, while the golf course never expanded, the Oka Crisis further affirmed the importance of Indigenous national sovereignty.

Works Cited

- Alfred, Gerald R. Heeding the Voices of our Ancestors: Kahnawake Mohawk Politics and the Rise of Native Nationalism. Toronto: Oxford UP, 1995. Print.

- Fee, Margery.

Reading Aboriginal Lives.

Editorial. Canadian Literature 167 (2000): 5–7. Print. - Hill, Gord. The 500 Years of Resistance Comic Book. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp, 2010. Print.

- New, W. H.

Learning to Listen.

Editorial. Canadian Literature 124–25 (1990): 4–8. Print. (PDF)

©

©