Essex County by Jeff Lemire (Top Shelf, 2009) Essex County © Jeff Lemire. Excerpts reprinted with permission.

Comics have gained cultural capital as a storytelling medium. Major fiction and non-fiction comics have won awards and have gained prestige. However, debates about the value of comics continue. For example, Jeff Lemire’s award-winning graphic novel Essex County was nominated for the CBC Canada Reads “battle of the books” competition in 2011 (also see our chapter on Canada Reads). The book topped the online reader polls (“Canada Reads” n. pag.) and was unanimously affirmed by the contestants as a powerful compilation of interwoven stories with rich characters. Yet the book was voted off in the first round. In justifying her vote to remove the book, popular interior designer Debbie Travis claimed that Essex County was “not [a] novel” due to its “lack of writing.”

The high-profile exposure of Canada Reads raised similar sentiments in others, even while Lemire was promoting Essex County. Lemire reveals, [s]ince Canada Reads, 70 per cent of the questions are ‘does your book deserve to be in this competition?’

(“Homerun” n. pag.). Rather than accept the book as just another novel in the competition, Lemire’s graphic novel was perceived as an outsider, a text that was incompatible with the category of literature and incapable of properly promoting literacy. As Katherine Collins (formerly Arn Saba) recalls in her radio documentary “Comics: The Continuous Art” for CBC Radio’s program Ideas,

Comics, I discovered, are not art. Comics are always discussed as graphic art, or narrative literature. They compare badly to both. We lack any organized set of standards by which to discuss whether or not a comic strip is successful as a comic strip. A critical vocabulary is what we need.

Although critics have often excluded comics from both traditional artistic and literary traditions (Beaty), American cartoonist Will Eisner considers this exclusion an opportunity. In Canadian director Ron Mann’s award-winning documentary Comic Book Confidential (1988), Eisner says that his relative incompetence in writing and painting enabled him to create a competency in comics that led to a successful career.

Comics as Literature: Institutional and Educational Considerations

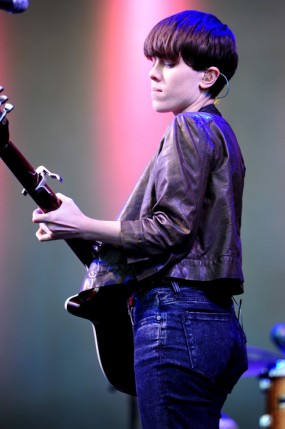

Musician Sara Quin, a Canada Reads panellist in 2011. By Stuart Sevastos [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The image/text dichotomy is a traditional Western concept. However, as Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas’ Red: A Haida Manga (2009) makes clear, many cultures do not see the visual and the verbal as belonging in separate categories and do not see images as supplementary or inferior to writing. The Mayan and Aztec codices or “screenfold books,” for example, include both words and pictures as vital components. And Japanese manga, Yahgulanaas’ model for Red, have had a wide and important influence on readers worldwide.

The negative fate of Essex County on Canada Reads suggests positioning comics as literature might prove to be difficult. This difficulty has historical and educational precedent. Many types of books use images to contribute to the narrative. Images as well as words compose what literary scholar Rachel Malik repeatedly calls the “horizons of the publishable,” since both images and text present opportunities for expression through print. Yet images and text are valued differently. Images in print texts are commonly viewed as illustrative or supplemental rather than vital to the meaning. In children’s picture books, images serve as informational anchors to “define the meanings of the accompanying word” (Nodelman 2) in order to develop language literacy. Comics have also been used in educational settings to inspire and facilitate literacy. This notion of images as supplemental prioritizes print as the mode of communication and information, making images into superficial flourishes. In this model, comics will always come out as second-rate.

Works Cited

- Gabilliet, Jean-Paul.

Comic Art and bande dessinée: From the Funnies to Graphic Novels.

The Cambridge History of Canadian Literature. Ed. Coral Ann Howells and Eva-Marie Kröller. New York: Cambridge UP, 2009. 460–77. Print. (Link) - Malik, Rachel.

Horizons of the Publishable: Publishing in/as Literary Studies.

ELH 75.3 (2008): 707–35. Print. Canada Reads 2011 People’s Choice Poll.

CBC Books: Canada Reads. 10 Feb. 2011. Web. 1 Mar. 2014. (Link)- Nodelman, Perry. Words About Pictures: The Narrative Art of Children’s Picture Books. Athens: U of Georgia P, 1988. Print.

Comics: The Continuous Art.

Narr. Arn Saba. Ideas, CBC. 12 Feb. 1979. Radio. CBC Digital Archives. 10 May 2013. Web. 8 May 2014. (Link)- Screech, Matthew. Masters of the Ninth Art: Bandes Dessinées and Franco-Belgian Identity. Liverpool: Liverpool UP, 2005. Print.

©

©