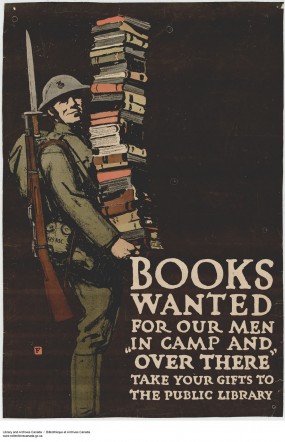

This poster from World War I is an example of the relationship between literacy, nationalism, and militarism. Library and Archives Canada, 1983-28-1063, e010697694-v8

The development of Canadian literature and culture has been informed by political policies surrounding support for a range of institutions tied to the arts in Canada. However, political mandates and legislation have also constrained the arts, such as through obscenity laws that restrict what can be produced and distributed. This was especially salient in the 1940s and 1950s, with the rise of Canadian cultural nationalism in opposition to what was perceived as cultural imperialism from the US.

The Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences (commonly called the Massey Commission) assessed the nation-wide role of various media (radio, television, etc.) and institutions (universities, publishers, etc.). They were charged with recommending how best to support and promote the cultural vitality of Canada. From this process, their 1951 report (commonly called the Massey Report) recommended “[t]hat a body be created … to stimulate and to help voluntary organizations within these fields, to foster Canada’s cultural relations abroad,” (377; ch. 25) and to provide grants and scholarships to help create Canadian culture. This influential document led to many changes in governmental support of the arts and social sciences in Canada. One important development was of the Canada Council for the Arts, which, to this day, is involved in distributing significant grants to publishers and to writers, artists, and other creators, including cartoonists.

Criminalizing Comics

MP E. Davie Fulton authored the Fulton Bill that banned crime comics in Canada. Library and Archives Canada, PA-125799, a125799

With this seemingly positive governmental engagement with arts and culture in Canada, it may come as a surprise that at around the same time, on 10 December 1949, the Parliament of Canada passed the “Fulton Bill” (Bill 10), named after its author E. Davie Fulton. The Fulton Bill revised the Criminal Code of Canada and “made it an offence to print, publish, distribute, or sell ‘any magazine, periodical or book which exclusively or substantially comprises matter depicting pictorially the commission of crimes, real or fictitious” (Bell, “Crackdown” 95). This censorship law specifically targeted comics in order to counteract a perceived sense of their promotion of juvenile delinquency. A secondary, but important, goal of the Fulton Bill was to promote Canadian cultural sovereignty, since many of the comics that the bill deemed as offensive were being imported from America.

As the Minister of Justice, Fulton would later author Bill C-58, a sweeping amendment to the Criminal Code of Canada, that passed on 10 July 1959. As Nick Mount notes,

Fulton was a nationalist. The real target of Bill C-58 was exactly what he said it was: not literature, but the American pocketbooks and comics that prompted CBC Radio producer Robert Weaver (himself no Conservative) to complain that same year about Canadian newsstands “groaning with investigations of homosexuality, lesbianism, prostitution and drug addiction, miscegenation, and juvenile delinquency.” Bill C-58 was the stick to the Canada Council’s carrot: one to promote Canadian high culture, the other to proscribe American popular culture. (n. pag.)

Bill C-58 promoted cultural sovereignty and encouraged social hygiene. Fulton’s thought of comics as “‘a certain type of objectionable material … being sold to the young people of our country with impunity’” (qtd. in Woodcock 7).” The Fulton Bill and Bill C-58 effectively removed comics from the newsstands.

Publishers and critics alike contested the laws; George Woodcock—editor of the then-fledgling journal Canadian Literature—warned, “this legislation [Bill C-58] marks no advance at all in the safeguarding of literature and, in fact, introduces new perils and uncertainties into the process of publication” (4). He concludes that, “our legislators have imposed on us an equivocal, hasty and dangerous law which can only bring a new element of insecurity into literary life” (8).

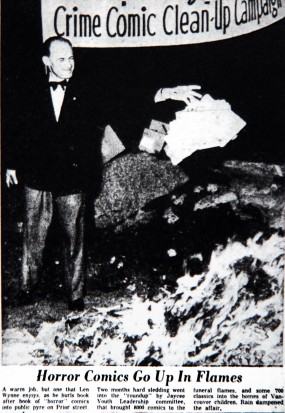

Comic book burning on Prior Street, Vancouver, BC (December 1954) Public domain (from Vancouver Noir: 1930–1960 by Diane Purvey and John Belshaw (Anvil Press 2011)

Fulton’s focus on comics censorship was fueled by a false belief that they promoted juvenile delinquency. This view was already prominent, but was further promoted by Dr. Frederic Wertham in his bestseller, The Seduction of the Innocent (1954). In his book, Wertham, a child psychiatrist and critic of mass media (see Beaty), uses anecdotal evidence to dismiss the conclusions of both Canadian and American psychological associations, which had stated that there was no evidence correlating comics with delinquency (see Gabilliet, Of Mice 22–32). This criminalization of comics led to crippling constraints on the comics industry, both in Canada and later in the US when Fulton testified before a US Senate committee that developed the laws against comics there (Nyberg 56).

Fulton’s emendations of the Canadian Criminal Code remain law to this day, leaving it up to the whim of policy makers and the public how its legislation of censorship and criminality of purportedly obscene materials including comics are enforced. Comics are still regularly seized by border agents if they are deemed “obscene” (see Khouri as well as the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund)

Comics and Education

Fulton’s and Wertham’s success in the 1950s meant that comic books came to be pervasively known as “the enemy of education” (Dorrell, Curtis, and Rampal 232). Perhaps even more important than the criminalization of comics was the idea that “comic books are death on reading” (Wertham 121). As education researchers Elaine Millard and Jackie Marsh show, even in contemporary English society,

In many people’s minds there remains a rather simplistic correlation between ‘looking at pictures’ and a deficiency in literacy, as it is frequently assumed that only those who are unable to read the words have a need for illustration. Visual literacy, except in its highest manifestations in the work of designers and classical artists, is rarely granted status within our education system. Teachers have been educated to consider the movement from pictures to words largely as a matter of intellectual progression. (27)

The hierarchal dualism construes the rising prominence of images as a threat to literacy or as a sign of impending illiteracy. W. J. T. Mitchell refers to this response to images as the “fallacy of the pictorial turn, a development viewed with horror by iconophobes and opponents of mass culture, who see it as the cause of a decline in literacy” (“Showing” 172). This perspective is only possible if one assumes that images and texts work separately, rather than supporting each other to make complex meanings.

Esteban March’s El becerro de oro (The Golden Calf) (1630) Fundacion Banco Santander, via Wikimedia Commons.

The issue itself follows in an even longer tradition of thought about language and images, which is relevant to the history of the moralistic criminalization of comics as well. A common distinction associates words “with law, literacy, and the rule of the elites” and associates images “with popular superstition, illiteracy, and licentiousness” (Mitchell, “Visual” 15). Such a distinction includes influential cases like the Judeo-Christian story that contrasts Moses and his stone tablets of the written law with the Israelites and their sinful idolatry of a golden calf (15). This story distinguished between the Word of God, as carved into the tablets, and the Israelites’ idolatry of “graven images” (King James Bible, Exod. 20:4, emphasis added). Distinctions like this filter communicative modes through moralistic ideologies, determining their value before they are even used.

Rather than maintain the primacy of the word, critics like W. J. T. Mitchell, as well as popular advocates like Sara Quin, push us to develop a more hybrid and egalitarian approach that considers words and images in conjunction with each other rather than in opposition. Such an approach attempts to resituate the verbal and visual modalities in relation to inherited cultural values and modes of evaluation.

Works Cited

- Bell, John. Invaders from the North: How Canada Conquered the Comic Book Universe. Toronto: Dundurn, 2006. Print.

- Canada. The Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences 1949–1951. Ottawa: Edmond Cloutier, 1951. Web. 13 Apr. 2014. (Link)

- Gabilliet, Jean-Paul.

Comic Art and bande dessinée: From the Funnies to Graphic Novels.

The Cambridge History of Canadian Literature. Ed. Coral Ann Howells and Eva-Marie Kröller. New York: Cambridge UP, 2009. 460–77. Print. (Link) - Beaty, Bart. Comics versus Art. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2012. Print.

- Bell, John.

Crackdown on Comics, 1947–1966.

Beyond the Funnies: The History of Comics in English Canada and Quebec. 24 June 2002. Web. 9 May 2014. (Link) - Dorrell, L., D. Curtis, and K. Rampal.

Book Worms without Books? Students Reading Comic Books in the School House.

Journal of Popular Culture 29 (1995): 223–34. Print. (Link) - Gabilliet, Jean-Paul. Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books. Trans. Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2010. Print.

- King James Bible. The Official King James Bible Online. 2014. Web. 16 May 2014. (Link)

- Khouri, Andy.

Indie comics seized by Customs agents at U.S.-Canada Border.

Comics Alliance. 13 May 2011. Web. 16 May 2014. (Link) - Millard, Elaine, and Jackie Marsh.

Sending Minnie the Minx Home: Comics and Reading Choices.

Cambridge Journal of Education 31.1 (2001): 25–38. Print. (Link) - Mitchell, W. J. T.

Visual Literacy or Literary Visualcy?

Visual Literacy. Ed. James Elkins. New York: Routledge, 2008. 11–29. Print. - Mount, Nick.

What Thunder Bay Burned: And How Lady Chatterley Wrote Our Obscenity Law.

The Walrus. Jan./Feb. 2010. Web. 14 Feb. 2014. (Link) - Nyberg, Amy Kiste. Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 1998. Print.

- Wertham, Frederic. Seduction of the Innocent. New York: Rinehart, 1954. Print.

- Woodcock, George.

Areopagitica Re-written.

Canadian Literature 2 (1959): 3–9. Print. (PDF) - Mitchell, W. J. T.

Showing Seeing: a Critique of Visual Culture.

Journal Of Visual Culture 1.2 (2002): 165–81. Print.

©

©