The Colonial Gaze

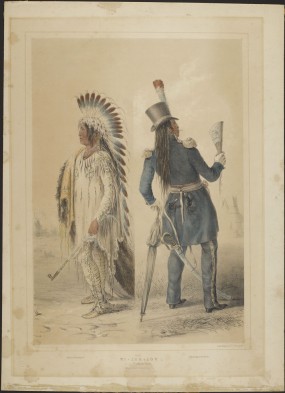

A Siouan/Assiniboin chief, before and after civilization: Wi-Jun-Jon by George Catlin, 1844 Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1970-189-152, C-041826. W.H. Coverdale Collection of Canadiana

Kent Monkman is a Cree and Irish multimedia artist from Manitoba. In his art, Monkman reimagines colonial-settler relations through an Indigenous lens. According to M. Melissa Elston, Monkman accomplishes this “in a series of playful ‘scenic’ paintings by reconfiguring images and forms of previous Euro-American art movements: Landscape painting, American Western art and neoclassicalisms in particular” (181). Monkman is especially critical of the way that artists depicted North America with a paucity of Indigenous peoples present. As Elston argues, “[d]espite continued Native presence in the lands depicted by white painters, natives themselves were seldom seen in these sweeping, empty vistas” and “[w]hen Natives figures were portrayed, they were portrayed in a way which constructed them as dying” (183). Such depictions attempted to affirm the inevitability of Western colonization.

Mary Greyeyes purportedly being blessed by her native Chief prior to leaving for service in the CWAC, September 29, 1942. Canada. Dept. of National Defence, Library and Archives Canada: PA-129070.

Photographers like Edward S. Curtis, and artists like George Catlin, tried to freeze Indigenous peoples in culture in time, believing that Indigenous cultures were static systems of belief, rather than dynamic and malleable interactions with the changing conditions produced by globalization and colonization. The implication of such works was that changes to Indigenous cultures were evidence of their corruption rather than adaptation.

These artists produced a wide array of portraits and sketches of events, serving to document the cultures before they were purportedly corrupted beyond recognition and erased by the presumed superiority of Western civilization. Ironically, the photographers and artists regularly changed the outfits and other cultural paraphernalia in order to construct an idealized image of the noble and vanishing “Indian.” Thus, these documents reflect the colonizing gaze of the artists more than necessarily the peoples they sought to document. As seen here, such stagings of noble and vanishing Indigeneity were also used shortly after this time as a means of promoting the war effort: see the evocative story of Mary Greyeyes by Melanie Fahlman Reid on this famous Canadian war photograph in “What Does This Photo Say?”

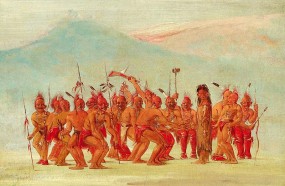

“Dance to the Berdache by George Catlin (ca. 1830s): A depiction of a ceremonial dance of the Sac and Fox peoples of the Great Plains celebrating the two-spirited person. Wikimedia Commons

Importantly, these artistic instantiations of the colonial gaze also assert Western gendered roles and values that do not necessarily reflect those of Indigenous cultures. For instance, Mary Greyeyes is positioned in submission to the man, while receiving a stereotypically Western blessing. Other images similarly reinforce gendered activities without recognizing the differences in approaches to gender and sexuality. For instance, many Indigenous cultures include matrilineal heritage, through which heirlooms and stories are passed down through the woman in the family, which contravenes the Western patriarchal system (this informs the narrative in Eden Robinson’s Monkey Beach). Likewise, the West viewed sexuality in heteronormative ways, whereas many Indigenous communities embraced and honoured other gendered experiences, such as those of two-spirited people. While artists like Catlin obviously were exposed to these ideas, and even documented them—such as in the sketch seen here—these differences were dampened and dismissed through the belief that static Indigenous differences would simply vanish under the presumed superiority of the flexible colonial culture.

Monkman’s Response: Miss Chief Eagle Testickle

Monkman’s art is based on the idea that Indigenous cultures in North America were not static. Rather, according to Monkman,

Aboriginal people had to be innovative to adapt and survive. The attempts of George Catlin to freeze Aboriginal people into a time capsule is counter to the philosophy I was taught by my Cree family, which was to move towards the future and not be afraid of taking something and making it your own. Whether you play the piano or make paintings, adapting influences from other cultures is a very empowered way of thinking about who you are. A lot of my work deconstructs received ideas about Aboriginal people: for instance, the notion that it is a negative thing that our culture has changed. (51)

This idea of deconstruction is critical to understanding Monkman’s art. By deconstructing, Monkman does not mean destroying. Rather, to deconstruct the past is to take it apart, rearrange it, and change it.

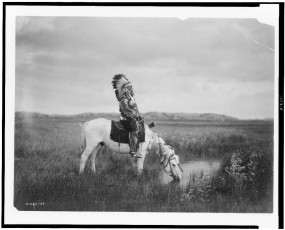

“An oasis in the Badlands by Edward S. Curtis, ca. 1905. Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-107914

This exercise considers a still-image from one of Monkman’s short films that deconstructs the iconographic photography and artistic representations discussed above. Here Monkman deconstructs and re-presents some classic motifs from Edward S. Curtis’ photography and the genre of the Western. There are particularly clear resonances between the photograph by Curtis seen here, of a lone Oglala man on a horse, and the still from Monkman’s film. Such resonances foreground the alterations and deconstructions.

One of the ways that Monkman deconstructs the past is through his alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, a trickster figure who is openly sexual. According to Monkman, “Aboriginal sexuality has been colonized” (46). In particular, the influence of Christianity created a “reduction of varied sexual expression in Aboriginal communities: polygamy and homosexuality became taboo. Of course, there were also the residential schools, where many Aboriginal people were victimized by sexual predators” (46). Miss Chief is a character that Monkman uses to deconstruct and unsettle settler-colonial relationships. Through her, Monkman reimagines contact between settlers and Indigenous peoples as being shaped by desire, sexuality, and play. Miss Chief, rather than being a helpless victim of white men, actively seeks out sexual encounters with settlers and, in turn, engages with settlers in transgressive, playful, sexual experiences.

Miss Chief also appears in some of Monkman’s paintings, which often add Indigenous figures to classical landscape pieces and other artworks to illustrate how the colonial, artistic gaze attempted to erase the Indigenous peoples from North America. In this way, Miss Chief, in the words of Thomas King, overtly acts as an “Inconvenient Indian” in order to signal the hostility and normativity of the colonial gaze in relation to Indigenous and gendered differences.

Exercise

Kent Monkman as his alter-ego “Miss Chief Eagle Testickle.” Still from Group of Seven Inches (2005). Reproduced with permission of the artist.

Examine and discuss this still-image of Monkman dressed as Miss Chief. Some questions to consider while close reading this image include:

- How does this image compare to the one by Curtis above?

- What is the role of drag in Monkman’s image?

- What is the role of costuming and why might Monkman blend a traditional looking headdress with platform high-heeled shoes?

- How does this image deconstruct the idea of the “vanishing, noble Indian” from Western art and movies?

- How does this image try to reimagine Indigenous culture as dynamic?

©

©