Now that we’re familiar with the Writing and Publication Program’s (WPP) history, we can return to the questions raised by Graham Huggan about official multiculturalism in this chapter’s introduction—political questions about whose interests the policy actually serves, and how it affects literary authors—and think alongside scholars who have grappled with them in relation to funding programs specifically. In asking whether multiculturalism is a “celebration of cultural difference” or rather a “smokescreen” type of “commodified eclecticism” (83), Huggan frames some of the broad terms that have characterized debates over multiculturalism since the 1980s (see Contesting Multiculturalism), and scholarship on the policy’s material effects in the cultural realm are similarly marked by significant ambivalence. On the one hand, the WPP’s funding of literature created new opportunities for many minoritized writers who received financial assistance and recognition; on the other hand, scholars are critical of how the government has strategically funded minority cultural production in order to construct, contain, and manage ethnicity in service of its official policy.

Parallel Funding

Monument to Multiculturalism by Francesco Pirelli (Union Station, Toronto). Paul Bica, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

An influential critique of multiculturalism funding comes from sociologist Peter Li. In his essay “A World Apart,” Li argues that separate programs for minority artists create two separate “arts worlds,” and contain minority cultures in a marginal position. He contends that a program like the WPP “reinforces the artificial differences between racial minorities and majority Canadians, and marginalizes the artistic development of visible minorities” (366). In Li’s view, then, rather than promoting equality, a parallel structure creates and perpetuates a distinction between dominant and subordinate arts cultures by way of government intervention; moreover, it allows those wealthier “mainstream” institutions like the Canada Council to shirk their responsibilities toward equity. Li therefore finds official multiculturalism’s patronage of minority artists to be patronizing—a tokenistic strategy of recognition that leaves the dominant culture unchanged.

Responding to Li specifically, Judy Young offers a detailed defense of the WPP and its legacy. In her essay “No Longer ‘Apart’?” she takes issue with Li’s suggestion that parallel funding marginalizes minority artists—such marginalization, she argues, was the reality before official multiculturalism even existed (107). Recounting the many ethnic minority writers who benefited from the WPP’s financial support, and whose work is now part of the “mainstream” of Canadian literature, Young questions whether it is even accurate to suggest that two “arts worlds” still exist. The debate between Li and Young is part of a larger critical discussion about whether affirmative or equity-oriented funding programs, in design or effect, redress disparities or reinforce the structural conditions that produce marginalization.

Commodifying and Managing Ethnicity

Supporters of the WPP like Young and Austin Cooke point to statistics and figures—the number of writers who have received funding, and the awards and achievements of their writing—as evidence of the program’s success. Yet we should consider how these accounts risk giving the WPP credit for wider forces that shape the literary field, and tend to diminish the creative labour and talent of writers themselves. Indeed, given the WPP’s partisan goal to promote the government’s vision of multiculturalism, the very notion of “success” needs to be unpacked: success for whom? Sheryl Hamilton argues that the government’s goal with these funding programs was not really to help minority artists at all, but to invest in their literary works as multicultural “art objects”—representations of ethnicity that can be identified, evaluated, funded, counted, and then held up as evidence of Canada’s multiculturalism and the success of its policy (16). By funding literature, Hamilton suggests, official multiculturalism also commodifies ethnic minority writers and their writing in order to manage a self-congratulatory display of national diversity.

Similarly, scholars have often critiqued the way multiculturalism policy objectifies ethnicity as something fixed, static, and communicable. For example, consider the WPP’s aim to fund ethnic minority writers on the basis that they “have a specific cultural experience to convey,” and how this aim might presuppose that a work of “ethnic” or “multicultural” literature is valued primarily for its ability to communicate the ethnic or cultural identity of its author. The notion that there is a “specific” essence to convey about any cultural experience works to foreclose the complexities of identity, community, and creative expression, and may reinforce stereotypical expectations that minority authors should write as representatives of an ethnicity or as experts in their cultural communities. Literary scholar Smaro Kamboureli has challenged how such policy objectives fix ethnic identity as a strategy of managing and reinforcing difference. Sardonically mimicking the official language of multiculturalism funding programs as commandments, Kamboureli writes: “Thou shalt be ethnic, our legislators say;… and thou shalt receive monies to write about thy difference (providing thou art a member of an ethnic organization that sponsors thy application)” (53). Scholars are thus concerned with the way official multiculturalism constructs and contains certain writing as “ethnic,” and the resulting “tendency to read multicultural literature through the racial or ethnic labels affixed to its authors” (Gabriel 31).

Agency of Writers

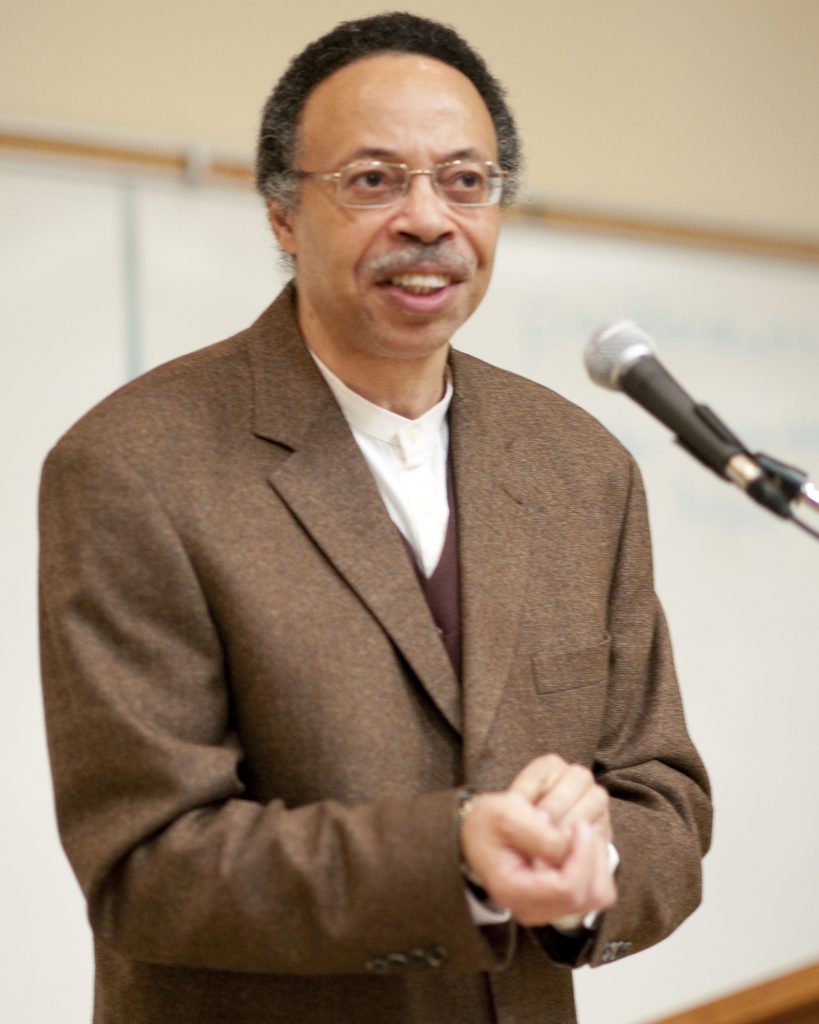

George Elliott Clarke, 2010. Mark Hill, CC BY-ND 2.0, via Flickr.

While most critics focus on “top-down” concerns with multiculturalism as a form of state management, some draw our attention to the “bottom-up” possibilities created by multiculturalism funding—that is, how writers themselves have used funding to their own ends, in ways that resist or exceed being managed. For example, Africadian scholar and writer George Elliott Clarke agrees with many critics that official multiculturalism reinforces “a concept of symbolic ethnicity” and positions ethnic minority writers as “other,” but he argues that “what counts ultimately is what ‘other’ groups, ‘other’ artists and writers … have made of it” (qtd. in Huggan and Siemerling 110). Clarke points to the reality that Canadian literature has become increasingly “polyethnic,” which he attributes in part to “the presence of government funds: that’s to say, our tax dollars have been partly returned to us to fund the establishment of journals and presses, to publish and circulate books, to give writers time to write, and so on” (110). So, while he remains critical of official multiculturalism, Clarke also highlights what its funding makes possible, and the agency of writers who have taken advantage of the WPP to open the cultural field of Canadian literature.

The Present and Future

More recent scholarship has grappled with the fact that multiculturalism no longer supports the literary arts. In her study of Canadian multiculturalism since 1971, Laura Moss notes that the WPP was ended at a time when program priorities moved away from “culture” and toward socio-political issues such as race relations and citizenship; in fact, she argues, the arts and culture have gone “from being absolutely central to unequivocally peripheral in the multicultural framework” (37). For some, this may seem positive: a longstanding critique of multiculturalism in Canada is that it celebrates culture superficially through “song and dance” rather than addressing deeper structures of inequality; critics of so-called “song and dance” multiculturalism might see the turn away from arts-based programming as practical. But scholars like Moss and Marjorie Stone view this turn skeptically, and as part of a broader devaluing of literature and the arts in Canadian social life. Given its creative capacity to explore questions of belonging, citizenship, identity, and community, literature has a great deal to contribute to discussions of Canadian multiculturalism, these scholars argue. Moss finds it troubling that literature and creative culture have disappeared entirely from official multiculturalism in response to the “anti-song and dance movement,” and suggests that it’s time Canadians and their government once again “take seriously the ‘culture’ in multiculturalism” (55).

Research Questions to Consider

- The Future. In light of these scholarly debates about the WPP’s history, what part should official multiculturalism play in the future political economy of Canadian literature? Is there need for, or value in, a new multiculturalism program geared toward supporting literature? If so, why? What might that program and its priorities look like? If not, why not? What are the pitfalls? Evaluate the present funding opportunities at the Department of Canadian Heritage (which currently houses multiculturalism) and its Multiculturalism Funding Program as you consider your position.

- Canada Council. Visit the Canada Council’s website to explore its current funding programs for literature, and evaluate the Council’s most recent Equity Policy. What are the values that inform its current positions on equity and diversity? What part does multiculturalism play in equity policy at the Canada Council today? Which strategic focus areas are prioritized in its administration of government funds?

- Funding Indigenous Literature. Official multiculturalism and its programs were not designed to support Indigenous peoples in Canada—in fact, Indigenous peoples and governments are exempted from the legal provisions of the Multiculturalism Act. In Producing Canadian Literature, Stó:lō author Lee Maracle describes her experiences being denied multiculturalism funding in the 1970s. “I appreciate there are people who have complaints about multicultural funding,” she says, “but all the cultures in this country have more access to Canada’s media than Aboriginal people” (50). What sources of funding are available for Indigenous authors today? Have new programs been created to support Indigenous writing? What concerns have Indigenous authors raised about official multiculturalism and the political economy of Canadian literature?

Works Cited

- Gabriel, Sharmani Patricia. “Interrogating Multiculturalism: Double Diaspora, Nation, and Re-Narration in Rohinton Mistry’s Canadian Tales.” Canadian Literature 181 (2004): 27-41. Print.

- Hamilton, Sheryl. “‘Creative and Cultural Expression’ but not Art: Multiculturalism Arts Funding as Cultural Management.” Alternate Routes: A Journal of Social Research 13 (1996): 3-22. Print.

- Huggan, Graham, and Winfried Siemerling. “Canadian Writers’ Perspectives on the Multiculturalism Debate.” Canadian Literature 164 (2000): 82-111. Print.

- Kamboureli, Smaro. “Of Black Angels and Melancholy Lovers: Ethnicity and Writing in Canada.” Us/Them: Translation, Transcription and Identity in Post-Colonial Literary Cultures. Ed. Gordon Collier. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1992. 51-62. Print.

- Li, Peter S. “A World Apart: The Multicultural World of Visible Minorities and the Art World of Canada.” Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology 31.4 (1994): 365-391. Print.

- Maracle, Lee. “Changing the Way Canada Sees Us: Interview with Lee Maracle.” Producing Canadian Literature: Authors Speak on the Literary Marketplace. Ed. Kit Dobson and Smaro Kamboureli. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2013. 47-60. Print.

- Moss, Laura. “Song and Dance No More: Tracking Canadian Multiculturalism Over Forty Years.” Zeitschrift für Kanada-Studien 31.2 (2011): 35-57. Print.

- Stone, Marjorie. “SSHRC’s Strategic Programs, the Metropolis Project, and Multiculturalism Research.” Retooling the Humanities: The Culture of Research in Canadian Universities. Ed. Daniel Coleman and Smaro Kamboureli. Edmonton: U of Alberta P, 2011. 133-59. Print.

- Young, Judy. “No Longer ‘Apart’: Multiculturalism Policy and Canadian Literature.” Canadian Ethnic Studies 33.2 (2001): 88-116. Print.

©

©