While the introduction to this chapter provides a general history of Canadian comics, what follows is a more thorough examination of significant movements in Canadian comics, starting with the English Canadian tradition and moving roughly chronologically from the earliest examples in the form of editorial cartooning and illustrated news to the superhero comics of the Second World War. This section then shifts to briefly review Quebecois comics traditions before considering the role of the alternative comics movement in allowing other voices to join the comics conversation. The section concludes with a consideration of how larger Canadian culture and political institutions have responded to these comics traditions.

Fig 3.1 Kate Beaton, creator of Hark! A Vagrant, at the Stumptown Comics Festival, 2010. Joshin Yamada, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia.

Editorial Cartooning Tradition

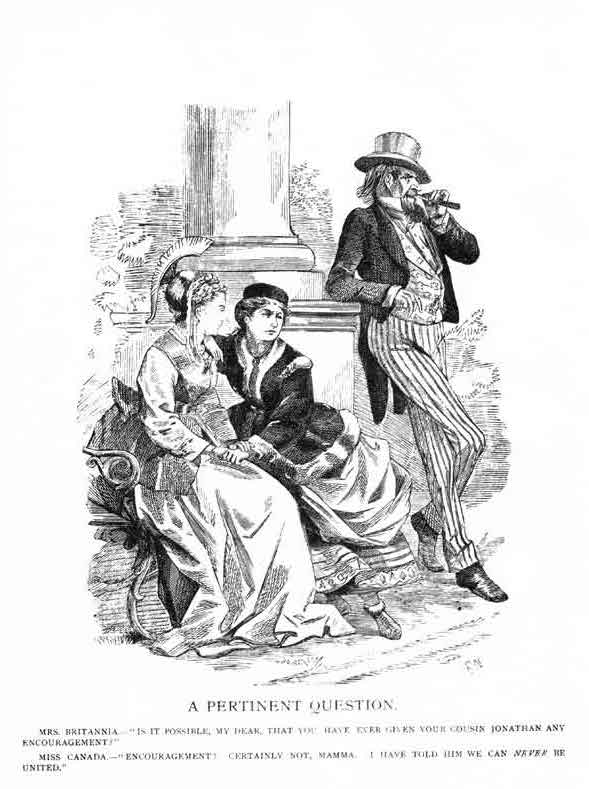

In both English and French Canada, the longest-running type of comics by far is the editorial cartoon, a tradition dating back at least as far as the sketches produced by George Townshend at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. From the mid-1800s, however, comics found their way into Canadian homes in publications like Punch in Canada and Canadian Illustrated News (Bell 19); significant artists in this period include John Wilson Bengough, with his 1873 comics weekly Grip, mostly covering current affairs, and Henri Julien, who in 1888 was hired as Chief Artist at the Montréal Star and became Canada’s first full-time newspaper cartoonist (Bell 20). This history of editorial cartoons imbues a strong satirical and political tradition to both French and English Canadian comics that we see evoked in the work of contemporary artists like Kate Beaton of Hark! A Vagrant (a popular webcomic that riffs on Canadian history, popular culture, and feminist themes, now published in two collections by Drawn & Quarterly). For example, in Bengough’s work, we often see Canada depicted as a young woman under the thrall of the handsome and seductive Cousin Johnny, who represents the US; she is typically also guided by the matronly Mother Britannia, who represents England (see image “A Pertinent Question” for an example). This humorously depicts the historical tensions of Canada’s national identity given its emergence between two greater political powers, which is a tradition carried on in Beaton’s work; see, for example, her comic depiction of the Fenian Raids (1860s and 1870s), “The Invasion of Canada,” where revolutionary Irish Americans mistakenly assume that Canada has a closer relationship to England than is accurate; as the characters repeatedly point out, “[t]here are a lot of holes in that plan.” While Canada is seen by America, in this example, as part of Britain, the reality of the relationship is much more complicated.

“A Pertinent Question” by J. W. Bengough. A Caricature History of Canadian Politics. 1886. Public Domain.

“Canadian Whites” Tradition

The Second World War was, as noted previously, one of the most significant eras in the history of Canadian comics publishing, mostly due to circumstance. As a result of the War Exchange Conservation Act of 1940, which restricted the import of non-essential items from the US in an effort to counter Canada’s growing trade imbalances during the wartime economy, American comics could no longer be imported for sale in Canada. Suddenly, a domestic market emerged in English Canada for the kind of superhero and action-adventure comics that had been provided by publishers south of the border. These comics are known as the Canadian Whites, named for the cheap white paper the comics were printed on. As Beaty and Dittmer and Larsen highlight, in this period, nationalist stories were in high demand. Artist Leo Bachle, who was only fifteen when he created Johnny Canuck, notes that he created the character because “every country had a hero” in wartime except Canada (qtd. in Hirsch and Loubert 24). These overtly nationalist titles were the most popular comics during the war: because of their wild popularity, John Bell generously terms 1941-1947 the “Golden Age” of Canadian comics (22). The wartime comics demand was so clearly manufactured by rationing that it effectively collapsed with the repeal of the War Exchange Conservation Act in 1951, which meant that American comics could once again be imported into Canada.

Quebecois Comics Traditions

Quebec’s unique cultural position means that its French-language comics tradition draws less on American pulp and superhero comics and more on the Franco-Belgian tradition of the bande dessinée—the French term for comics—which has historically treated comics not as light fare for children but as significant contributions to culture. The Catholic Church’s extensive use of history-in-pictures magazines and comic book Hérauts (“heralds”) meant that comic books were common in classrooms and in church. For these reasons, comics have traditionally been more highly valued and respected within Quebecois society than they have in English Canada (Pomerleau 105). However, as in English Canada, there was little French Canadian comics development before the 1970s, and during these years the comics popular in Quebec were primarily produced in Europe.

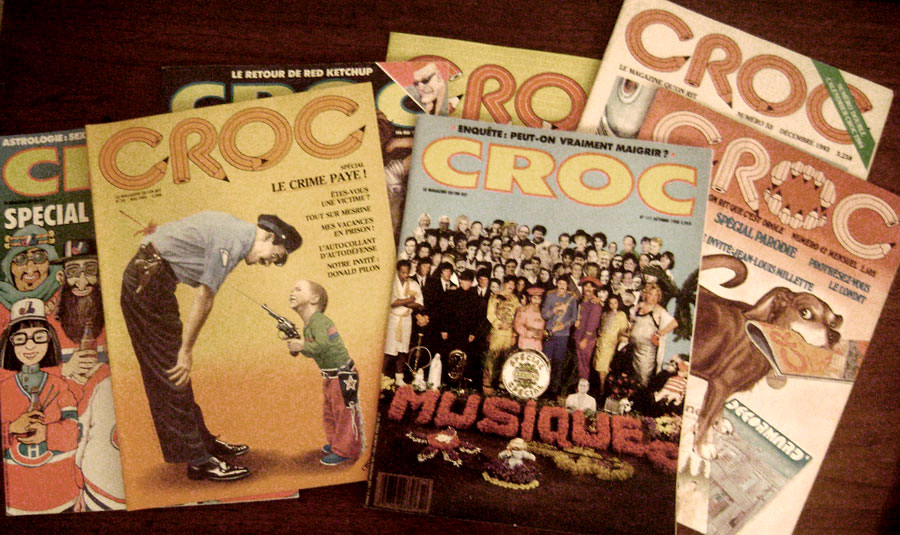

This shifted with what comics scholars call the Spring of Quebec BD (bande dessinée) in the 1970s, an explosive period of creative development and publication that followed the Quiet Revolution. The Quiet Revolution was a period of intense social, cultural, and political change in Quebec that saw a movement away from the traditionally powerful role of the Catholic Church and a rise instead in secularism, socialism, and separatism within the province. The Spring of Quebec BD is roughly analogous to the alternative comics movement in English Canada in the late 1970s; however, given the cultural value and stability of comics in Quebec prior to the late 1950s, the Spring of Quebec BD was much larger and more significant in its cultural impact. Occurring in the immediate aftermath of the Quiet Revolution, the focus of comics artists like the experimental underground comics collective Chiendent during this period was heavily on Quebec’s national identity, a theme that echoes in contemporary times in the work of artists like Michel Rabagliati. In The Song of Roland, Rabagliati uses the end of his father-in-law’s life to meditate on the Quiet Revolution’s failed dream of Quebec’s independence, with panels that feature Roland’s children asking if the moment for separatism has passed them by. On one page, we see Roland’s children first cheering for a celebration of Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day—the fête nationale du Quebec, originally a religious holiday that took on separatist overtones during the Quiet Revolution—and then sighing wistfully over a graveyard that seems to represent the end of Quebec’s nationalist moment. The vibrancy of comics culture in Quebec and its tradition of connecting with revolution and rebellion against established order make Quebecois comics particularly interesting to study, especially in the context of national identity.

Croc Magazine (1979-1995) published many Quebecois cartoonists during its run. Alphonse in Chains, Public Domain, via Wikimedia.

Alternative Tradition

Chester Brown, creator of Yummy Fur and Louis Riel: A Comic-Strip Biography, among others. Tabercil, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia.

In the 1970s, Canadian creators began to see significant successes—domestically and internationally—in the realm of alternative and independent comics. Major artists of this period include Chester Brown, whose collections of autobiographical comics, gospel adaptations, and other experimental content launched as Yummy Fur in 1979 and whose work includes Louis Riel: A Comic-Strip Biography (serialized 1999-2003 and collected in 2003), and Dave Sim. Sim’s Cerebus, a sprawling three-hundred-issue series beginning in 1977 and continuing today, was labelled by Bell in 1986 as “the country’s greatest achievement in comics art” (40). Sim, however, is not an unproblematic figure in Canadian comics: the misogyny found especially in his later texts reflects the kind of work that scholars like Mullins and Stanley actively resist. For example, in Issue #186 of his project, “Reads,” Sim writes: “Cerebus is a very weird little commodity in the context of the Female Emotional Void Age. It’s too small to pay attention to and too big to ignore. It wouldn’t be that big a stretch to categorize Reads as Hate Literature against women. All it would take is for one woman to be disturbed enough by Reads to file a lawsuit, or a women’s group to file a class-action suit, in this Fascistic Feminist country and that would be the ball game, wouldn’t it?” Certainly, the emergence of female comics artists like Julie Doucet (Dirty Plotte [1991]), Jillian and Mariko Tamaki (Skim [2008] and This One Summer [2014]), and Faith Erin Hicks (The Nameless City [2015]) have helped to broaden the scope of representation by creating a tradition that offers readers representations of a diversity of female bodies and voices to counter the existing male-dominated narratives.

As Dittmer and Larsen emphasize, the history of representation of Indigenous people in Canadian comics has been particularly poor, ranging from total absence to the white saviour narratives typical of Nelvana of the Northern Lights. In recent years, artists like Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas (Haida) have adopted comics as a way to tell Indigenous stories; in his 2009 book Red: A Haida Manga, Yahgulanaas steps outside of the Western comics traditions to adopt a Japanese manga style through which he addresses issues of colonization and community. In this comic, what would traditionally be used as a conventional border or gutter to delineate a story actually holds narrative significance, forcing the reader to reconsider both how comics work and, importantly, how borders/the border imposed by the settler-colonial state of Canada affect members of the Haida nation (this argument is more fully articulated in “Border Studies in the Gutter”; for how scholars analyze literary representations of borders, see Gillian Roberts’ CanLit Guides chapter, “Canadian Literature and the Canada-US Border”). In 2015, Moonshot: The Indigenous Comics Collection Volume 1 was published by Canadian publisher Alternate History Comics, following a successful crowd-funding campaign; Moonshot collects the work of dozens of Indigenous comics creators from across North America for the first time and provides readers with a useful cross-section of contemporary Indigenous voices in comics. A second volume followed in 2017. Other significant Indigenous comics creators include Swampy Cree writer David Alexander Robertson (7 Generations: A Plains Cree Saga [2013]) and Métis writer Patti LaBoucane-Benson (The Outside Circle [2015]).

Comics’ (Perceived) Value and Censorship

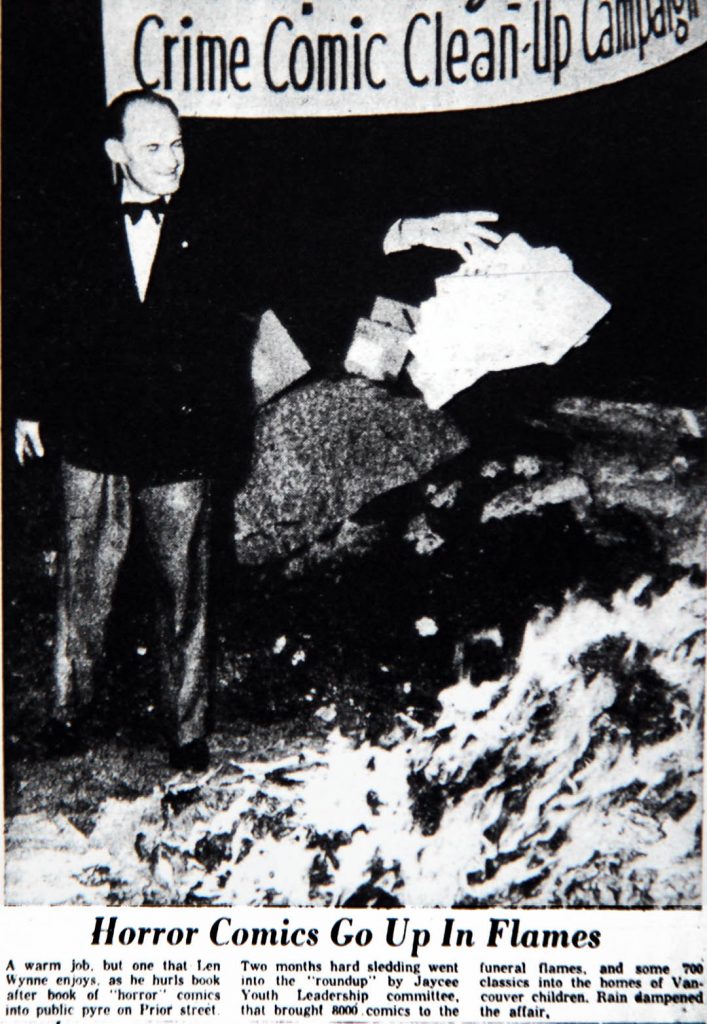

In the various traditions summarized above, comics have been subject to possible censorship due not only to their content, but to cultural assumptions about and evaluations of the form itself. In English Canada and the US, comics have consistently been seen as damaging or troubling material for young people; legal measures have historically been taken to try to sanitize or eliminate comic books. In Canada, on 10 December 1949, Parliament passed the “Fulton Bill” (Bill 10), named after its author E. Davie Fulton. The Fulton Bill revised the Criminal Code of Canada and “made it an offence to print, publish, distribute, or sell ‘any magazine, periodical or book which exclusively or substantially comprises matter depicting pictorially the commission of crimes, real or fictitious’” (Bell, “Crackdown” 95). This censorship law specifically targeted comics in order to counteract a perceived sense of their promotion of juvenile delinquency. A secondary, but important, goal of the Fulton Bill was to promote Canadian cultural sovereignty, since many of the comics that the bill deemed as offensive were being imported from America.

Comic book burning on Prior Street in Vancouver, BC. December 1954. Public Domain via Vancouver Noir: 1930–1960 (Anvil, 2011).

As the Minister of Justice, Fulton would later author Bill C-58, a sweeping amendment to the Criminal Code of Canada that passed on 10 July 1959. Bill C-58 promoted cultural sovereignty and encouraged social hygiene. Fulton thought of comics as “‘a certain type of objectionable material . . . being sold to the young people of our country with impunity’” (qtd. in Woodcock 7). The Fulton Bill and Bill C-58 effectively removed comics from the newsstands.

Publishers and critics alike contested the laws; George Woodcock—editor of the then-fledgling journal Canadian Literature—warned, “this legislation [Bill C-58] marks no advance at all in the safeguarding of literature and, in fact, introduces new perils and uncertainties into the process of publication” (4). He concludes that, “our legislators have imposed on us an equivocal, hasty and dangerous law which can only bring a new element of insecurity into literary life” (8).

Fulton’s focus on comics censorship was fueled by a false belief that they promoted juvenile delinquency. This view was already prominent, but was further promoted by Dr. Frederic Wertham, in his bestseller, The Seduction of the Innocent (1954). In his book, Wertham, an American child psychiatrist and critic of mass media (see Beaty), uses anecdotal evidence to dismiss the conclusions of both Canadian and American psychological associations, which had stated that there was no evidence correlating comics with delinquency (see Gabilliet). This criminalization of comics led to crippling constraints on the comics industry, both in Canada and later in the US, when Fulton testified before a US Senate committee that developed the laws against comics there (Nyberg 56).

Fulton’s emendations of the Canadian Criminal Code remain law to this day, leaving it up to the whim of policy makers and the public how its legislation of censorship and criminality of purportedly obscene materials including comics are enforced. Comics are still regularly seized by border agents if they are deemed “obscene” (see Khouri as well as the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund). For guidance on studying censorship in Canadian literature, see Lucia Lorenzi’s CanLit Guides chapter on “Literary Censorship and Controversy in Canada.”

Comics’ (Perceived) Value and Literary Awards

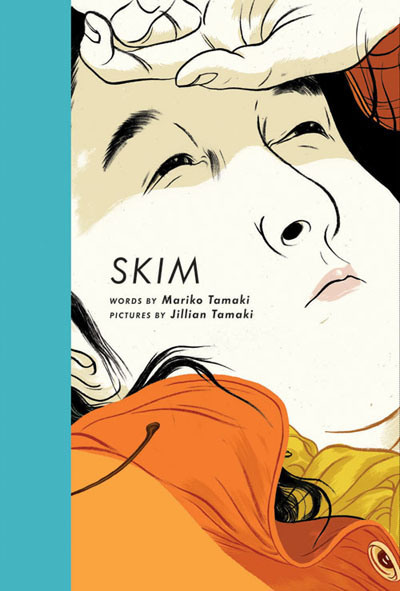

Skim by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki (Groundwood, 2008). Reproduced with permission from Groundwood Books.

While comics have historically been devalued, more recently, they have gained cultural capital as a storytelling medium. Major fiction and non-fiction comics have won awards; however, we can still see in contemporary literary awards culture that debates about the value of comics continue in Canada. One notable example is the case of Jillian and Mariko Tamaki’s young adult (YA) comic Skim, a coming-of-age story about a girl who feels like an outsider, which won a Doug Wright Award and was nominated for a Governor General’s Literary Award (GGs) in 2008. Currently the GGs, administered by the Canada Council for the Arts, explicitly do not accept any comics outside of the category of children’s and YA books. However, since it could be categorized as Young Adult fiction, Skim fit the GGs’ children’s literature award’s nomination criteria. But, another problem arose: the nomination was only for Mariko, who penned the words, excluding Jillian, who penned the images. This nomination suggested that the award committee prioritized the words over the images, reflecting a common bias against the image (see, for example, Mitchell). In response to this slight against Jillian, comics artists Chester Brown and Seth wrote an open letter in the National Post, urging the committee that she be included in the nomination. Many major comics creators across North America, including Art Spiegelman, publically endorsed Brown and Seth’s letter. The letter clarified that for comics creators, text should not be prioritized over images. While some comics employ more or less language, and more or less distinct imagery, these cannot be separately evaluated and prioritized, but must be recognized together. Of note, in 2014, when Jillian and Mariko Tamaki were nominated for a GG award again for This One Summer, another coming-of-age story, this time about female friendship, they were nominated in two categories, with Mariko nominated for writing and Jillian for illustration.

Another case of stigma against comics in literary awards is when in 2011, Jeff Lemire’s award-winning Essex County, a multigenerational graphic novel about hockey, superheroes, and life, was nominated for CBC’s Canada Reads “battle of the books” competition (also see the CanLit Guides chapter on Canada Reads). The book topped the online reader polls (“Canada Reads” n. pag.) and was unanimously affirmed by the contestants as a powerful compilation of interwoven stories with rich characters. Yet despite the agreement among contestants that Essex County is an exceptional work of art, the book was voted off in the first round largely due to anxiety about the form itself. For example, contestant and popular interior designer, Debbie Travis, declared that Essex County was “not [a] novel” due to its “lack of writing” when justifying her vote to remove the book (watch the introduction to and debate about Essex County). In Travis’ explanation, we again see how the persistent valuing of text over image shapes the evaluation of comics in Canada in literary awards.

Reflection Questions

- If the roots of English Canadian comics are in editorial cartoons and wartime superheroes, what might these two traditions offer to contemporary comics artists? Think about how editorial cartoons and wartime comics both address national political concerns, albeit from very different perspectives. Do you see a lot of satire and/or nation building when you look at Canadian contemporary comics today?

- Nationalist comics in World War II were almost exclusively about white male characters active in the war effort. If you were to design a character to reflect or resist Canada’s national identity today, who would that character be? How will readers know it is both Canadian and contemporary?

- Consider what you know about Quebec’s history and its ongoing role in Canada as a “distinct society” with its own cultural influences, including that of the Catholic church. Take this understanding and what you learned above on how comics developed differently in Quebec, and apply both to a comparative analysis of two comics published in the same time period: one from Quebec and one from another part of Canada.

- Compare the representation of women, people of colour, and/or those who are Indigenous in two comics: an early Canadian comic and one created more recently by a member of the represented community. What can you say about representations of identity through this exercise? What scholarly sources might you seek to help you further analyze the similarities and differences that you see?

Works Cited

- Beaton, Kate. “Invasion of Canada.” Hark, A Vagrant 364.

- Beaty, Bart. “The Fighting Civil Servant: Making Sense of the Canadian Superhero.” American Review of Canadian Studies 36.3 (2006): 427-39. Print.

- Bell, John. Canuck Comics: A Guide to Comic Books Published in Canada. Montreal: Matrix, 1986. Print.

- —. “Crackdown on Comics, 1947–1966.” Beyond the Funnies: The History of Comics in English Canada and Quebec. 24 June 2002. Web. 9 May 2014.

- Brown, Chester, and Seth. “An Open Letter to the Governor General’s Literary Awards.” Rpt. in “Comics’ Big Guns Take Aim at the Governor General’s Literary Awards.” Eureka. Brad Mackay. 12 Nov. 2008. Web. 11 Feb. 2014.

- Canada Reads 2011 People’s Choice Poll. CBC Books: Canada Reads. 10 Feb. 2011. Web. 1 Mar. 2014.

- Dittmer, Jason, and Soren Larsen. “Aboriginality and the Arctic North in Canadian Nationalist Superhero Comics, 1940-2004.” Historical Geography 38 (2010): 52-69. Print.

- Gabilliet, Jean-Paul. Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books. Trans. Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2010. Print.

- Gray, Brenna Clarke. “Border Studies in the Gutter: Canadian Comics and Structural Borders.” Canadian Literature 228-9 (2016): 170-87. Print.

- Hirsch, Michael, and Patrick Loubert, eds. The Great Canadian Comic Books. Toronto: Peter Martin, 1971. Print.

- Khouri, Andy. “Indie comics seized by Customs agents at U.S.-Canada Border.” Comics Alliance. 13 May 2011. Web. 16 May 2014.

- Lemire, Jeff. The Collected Essex County. Marietta, GA: Top Shelf Productions, 2011.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. “Showing Seeing: a Critique of Visual Culture.” Journal of Visual Culture 1.2 (2002): 165–81. Print.

- Mullins, Katie. “Questioning Comics: Women and Autocritique in Seth’s It’s a Good Life, If You Don’t Weaken.” Canadian Literature 203 (2009): 11-27. Print.

- Nyberg, Amy Kiste. Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 1998. Print.

- Pomerleau, Luc. “Quebec Comics: A Short History.” Canuck Comics: A Guide to Comic Books Published in Canada. Ed. John Bell. Montreal: Matrix, 1986. 103-13. Print.

- Rabagliati, Michel. The Song of Roland. Wolfville: Conundrum, 2012.

- Sim, Dave. Cerebus: Mothers and Daughters: Reads. Kitchener, ON: Aardvark-Vanaheim, 1994.

- Stanley, Marni L. “Drawn Out: Identity Politics and the Queer Comics of Leanne Franson and Ariel Schrag.” Canadian Literature 205 (2010): 53-68. Print.

- Tamaki, Jillian, and Mariko Tamaki. Skim. Toronto: Groundwood, 2008. Print.

- —. This One Summer. New York: First Second, 2014. Print.

- Walker, Alan. “Historical Perspective.” The Great Canadian Comic Books. Ed. Michael Hirsch and Patrick Loubert. Toronto: Peter Martin, 1971. 5-25. Print.

- Woodcock, George. “Areopagitica Re-written.” Canadian Literature2 (1959): 3–9. Print.

©

©