In his preface to the second edition of A History of Canadian Literature, W. H. New notes how much has changed in the study of Canadian literature between the first edition of his history in 1989 and the second edition in 2003. According to New, Canadian literature is a “history-in-process,” where

[p]olitical events have reshaped Canadians’ sense of themselves; critical fashions have altered, reassessing reputations, reconstructing canons, and reacting to modified social priorities and preoccupations. (xiii)

One major change to the study of Canadian literature is the shifting nature of the literary canon. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a canon is “[a] standard of judgment or authority; a test, criterion, means of discrimination” (n.2.c.). The canon is comprised of texts that are considered the essential readings of Canadian literature.

Canons are not objective and they do not reflect the best that has been said and written. Scholars make choices about what books are in or out of the canon based on collective value judgments—and who those scholars are matters. It is not a coincidence that a mostly male literary establishment declared that books that reflected their concerns, tastes, and desires were deemed the most worthy of study. Thus, the contents of a literary canon are grounded in whose judgments are used as a means of discrimination. One of the things that feminism has brought to discussions of the canon is the role of gender and sexism in these discussions.

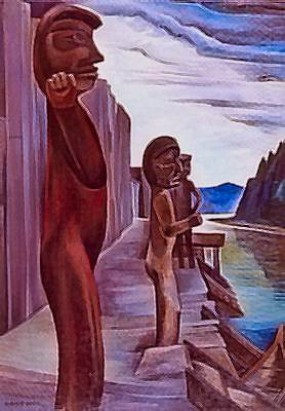

Emily Carr’s Blunden Harbour, c. 1930. National Gallery of Canada. Wikimedia Commons

The literary establishment has, historically, been made up of mostly middle and upper class heterosexual men who have, in turn, privileged books written by people who shared their values, tastes, and judgments. This has led to a Canadian fiction canon that is implicitly male-centric. For example, modernist literary critic Dean Irvine has shown that women played a large role as editors and writers of little magazines in Canada between 1916 and 1956, but that “women have so far remained peripheral to historical narratives of the little magazine in Canada” (4). Canadianist Carole Gerson notes a similar trend in anthologies. For example, she observes of one anthology: “on the cover is a painting by Emily Carr, who won a Governor General’s Award for Klee Wyck in 1941. Inside is the work of eighteen writers, three of them women, none of them Carr” (147). In that anthology, it seems that women’s works are considered best seen, not heard.

Literary canons have recently become malleable, new voices are being listened to, and more women are now working within the literary establishment and teaching books that speak to their interests. There is, however, still a long way to go before there is gender equality in the Canadian literary canon. Feminist critics in particular have rethought the process of canon formation and questions of literary value. In the process, feminist criticism has led to the recovery of writing by and about women—a recovery that would not have happened if feminists did not draw attention to the role that gender played in the formation of the Canadian literature canon.

Nalo Hopkinson, 2007 Sherurcij. Wikimedia Commons

Feminist scholars draw attention to the way that issues of gender specifically impacted the construction of the canon of Canadian literature. To some degree, the canon of Canadian literature has become more diverse since the 1970s, and now there are more texts written by women in anthologies and taught in classes. Authors such as Margaret Atwood, Alice Munro, Nalo Hopkinson, and Anne Michaels are literary celebrities in Canadian literature, and their works have international followings. One of the major projects of feminist scholarship is to encourage more texts by women to be published in Canada, and to recover the work of Canadian women authors who have been neglected by previous scholars. For instance, recent scholarship has reaffirmed the importance of E. Pauline Johnson’s (Tekahionwake) texts and performances, which were dismissed by early critics based on her gender, Mohawk ancestry, and popular style.

While the canon is clearly becoming more diverse, there are practical limitations to how diverse it can become. As Laura Moss notes in her editorial “Playing the Monster Blind? The Practical Limitations of Updating the Canadian Canon,” while the Canadian literature canon has changed, “[t]he possibilities of canonical expansion are at least in part governed by the sheer volume of work published …” (9). For example, Canadian Literature reviews about three hundred and twenty books every year. We are one of the larger book reviewers in Canada and yet we have to turn down the chance to review books every year. Canadian literature has reached a critical mass where it would not be possible for one person to read everything published by Canadian authors every year.

In discussing the expansion of the Canadian literature canon to include more texts by women it is helpful to note that the question of what is Canadian literature has always been complicated. According to Canadian literature scholar Faye Hammill,

canon-making [in Canada] has always posed a range of particular challenges, owing to the country’s shifting political structures, and the ethnic and linguistic diversity and complicated migrations of its populations. The difficulty of determining which authors and works count as Canadian is considerable, because many literary texts about Canada have been written by foreign explorers and travellers, or by recent immigrants, temporary visitors or Canadian-born expatriates. (16)

“Imaginary portrait of Jacques Cartier by François Riss, 1839, copied by Théophile Hammel ca. 1844. Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1997-218-1, C-011226

As Hammill further notes, challenges to the Canadian canon “are generally made in the name of one of more relatively excluded groups of authors” (16), such as Indigenous writers, writers of colour, and women. A further difficulty that Cynthia Sugars and Laura Moss note in commenting on the creation of their anthology Canadian Literature in English: Texts and Contexts, Volume II (2009) has to do with the issue of when Canadian literature begins (xii). For example, they begin the conversation with Jacques Cartier’s colonial contact narrative The Voyages (1534), but they also problematize the idea that Canadian literature begins with explorer narratives by including as an opening text “The First Words” by Mohawk writer Brian Maracle (Owennatekha). They do so “to represent the active role indigenous people have played, and continue to play, in shaping the development of modern-day Canada and Canadian writing” and to “[open] the collection not only by retelling one story of the creation of ‘Turtle Island’ (North America), but also by invoking the ceremonial ‘first words’ that preface any instance of storytelling” (xii).

With the ever-expanding canon, we have access to new and exciting voices from the past and present, but the cost of this expansion is the fragmentation of the field. Since it is no longer possible for one scholar to read every book published in Canadian literature in one year, many scholars have become decidedly specialized. University classes, moreover, rarely give the illusion of covering all of Canadian literature, or, for that matter, all of Canadian women’s literature. This raises the need for a self-reflexive practice that questions the values and assumptions that select the different stories we tell and affirm.

©

©