The following breakdown of The Gravel Pit

offers close reading strategies for formally innovative poetry.

As a concrete poem,

the very way that The Gravel Pit

is presented on the page asks us to think about how we go about reading it in the first place.

Do we read conventionally, from left to right and top to bottom? Or do we read through the various stanzaic groupings that are distributed down the page? The rough groupings of words offer a non-traditional, more schematic or pictographic ordering that suggests we take each group as a unit for analysis.

This doesn’t mean that there can’t also be connections between lines as well, but let’s start with these groupings first.

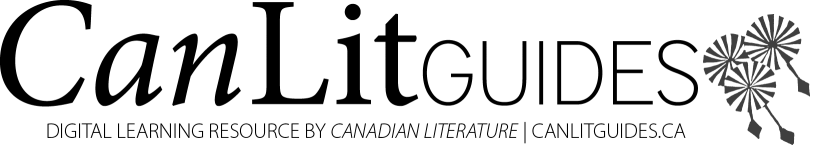

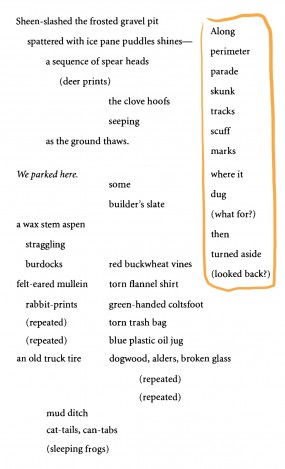

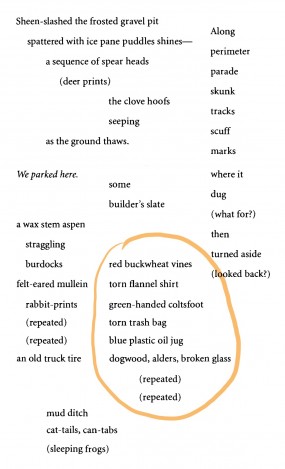

The first stanza (see Figure 1) sets the scene, denoting the spring-time frosty chill and thaw in a gravel pit. Note how the form of the stanza funnels down into the deer printswhich are seeping / as ground thaws.The imagistic qualities of these words funnel us down the page, making the static deer prints dynamic through the enactment of the seeping water. The notion of these deer prints tied to melting ice develops a sense of presence and absence, a slipping and sliding between the deer and ice that were there and the prints and water that remain. The consonance and assonance of the |

|

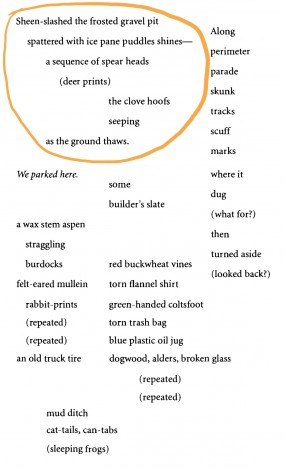

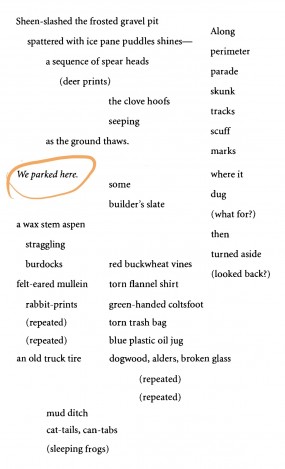

The second stanzaic form (see Figure 2) is foregrounded by the first line as it too goes along / perimeter.The skunk tracks reaffirm the sense given by the deer prints of life around but not present. It further layers on questions of intention in the parenthetical notes. This stanza marks out a peripheral space while filling it with traces of animal activities. It also suggests that we see the whole poem as a map of a gravel pit, as this peripheral location on the page is also overtly tied to its location in the world the poem describes. |

|

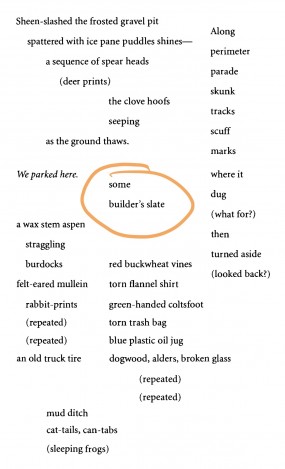

The third stanza (see Figure 3) is somewhat startling for a few reasons. It is the shortest one, but more importantly it is also the only stanza with a human perspective, locating the observational, narrative voice with the personal pronoun we.This stanza is also written in italics, which off-sets it from the rest of the poem and hints at handwriting. This handwritten note on the page in turn offers a personal touch or imposition in a space that is dominated by non-italicized type. In light of the map-like quality emerging with Stanza 2, this can also be read as a handwritten note-to-self. Combining the personal perspective with the handwriting sets up a space apart from the rest of the descriptions in the poem, perhaps as an |

|

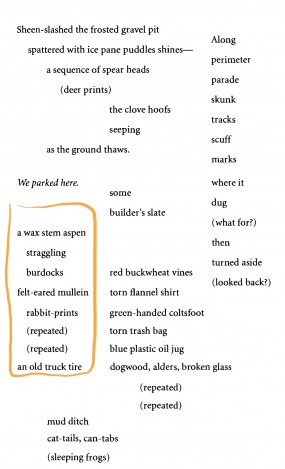

| The fourth stanza (see Figure 4) adds another human detail, but is indistinct other than as a pile of rubble. It sets up the space of human action, hinted at but not witnessed, much like the deer and skunk of the first two stanzas and the past tense note in the third. | |

The fifth stanza (see Figure 5) shifts in tone from the previous ones, offering an incomplete list of things observed. It presents a number of plants, as well as a hint of a rabbit through its repeated prints. This repetitious natural scene is disrupted by an old truck tirewhich ends (or perhaps stops or interrupts) the stanza. |

|

|

The sixth stanza (see Figure 6) is similar to the fifth, but incorporates more |

|

Finally, the poem ends with another brief description (see Figure 7) of a ditch where cat-tailsand can-tabsare equated through their similar verbal forms, but under which another animal presence sleeps. How might we interpret the equation of cat-tails and can-tabs? And how might we interpret this slumber underneath them? How do the frogs contrast with the other animals mentioned in the poem? |

Questions for Further Consideration

- What does it mean to have these various stanzas laid out on the page in such a way?

- How does this style shift the way we read the poem?

- How might it be significant that we can’t just read the poem in a conventional fashion, left to right, top to bottom? Consider how this change alters how we must conceptualize the poem as a different type of paper document such as a map, painting, or report.

Works Cited

- Lane, M. Travis.

The Gravel Pit.

Canadian Literature 170–71 (2001): 20. Print. (Link)

©

©