Short Textual Study: Lee Maracle’s “Yin Chin”

Stó:lō-Salish-Cree author Lee Maracle explores the intersections of Indigenous and diasporic communities in her poetry, autobiographic works, and fiction. Poems in Bent Box (2000), her novel Sundogs (1992), and her short story collection First Wives Club: Coast Salish Style (2010) can all be considered in these terms.

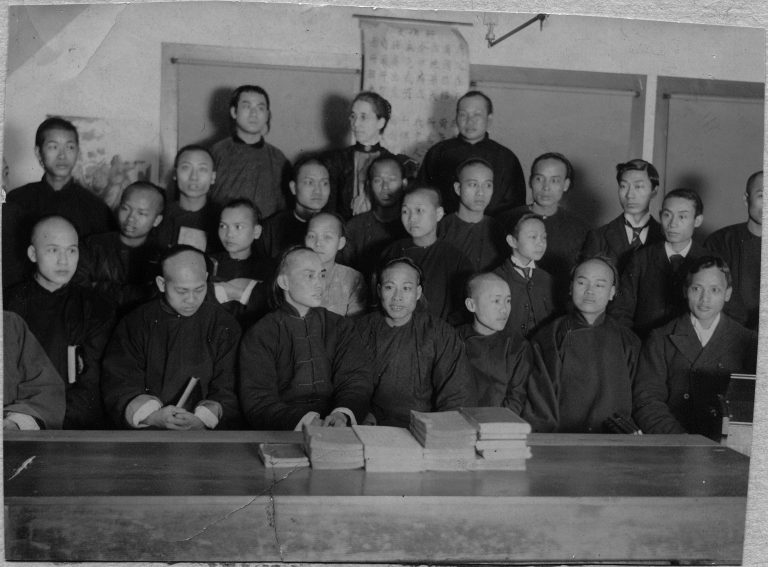

Here we will focus on a short and lesser known piece of Maracle’s titled “Yin Chin,” published in The Native Writers and Canadian Writing special issue of Canadian Literature. “Yin Chin” reflects on the narrator’s experience growing up as an Indigenous child in Vancouver’s Chinatown and examines Indigenous and diasporic intersections on Canada’s West Coast.

Discussion Questions

- Where and when does solidarity arise between the Indigenous and Chinese Canadian characters of “Yin Chin”? What about difference?

- As this chapter has shown, diasporic and Indigenous texts tend to trouble national categories. What cracks and fissures does “Yin Chin” show within narratives that suggest Canada is a welcoming and inclusive nation? What, according to Maracle, is the problem with arguments that Canada welcomes diasporic communities?

- Think about genre: how would you classify a story like “Yin Chin”? What about grammar? We typically understand grammar as the “rules” that structure written English: how does Maracle play with these rules, and why?

- Throughout this piece, Maracle’s narrative voice moves from memory to the present day, shifts that suggest time and age are significant themes to examine when analyzing this story. What differences does Maracle highlight between childhood and middle age? How does the title, epigraph, and dedication of “Yin Chin” expand the narrative’s timeline? Did you find the story’s temporal shifts jarring? Why does Maracle play with time?

- According to the closing lines of “Yin Chin,” what is the root of ignorance in Canada?

Long Textual Study: Dionne Brand’s What We All Long For

Dionne Brand’s celebrated novel What We All Long For is often read as a critique of the Canadian nation that is expressed through the novel’s racialized protagonists’ who repeatedly find themselves excluded from “regular Canadian life” (47). As noted in the CanLit Guides chapter to What We All Long For, Brand “engages carefully with the spaces of Toronto” because “the city is an active character involved in the lives of the human characters [that] activates or reveals various character attributes and binds together histories.” Brand’s representations of the city subtly expose the lack of clarity diasporic-Canadian communities can have regarding the Indigenous peoples whose land they occupy. The novel’s opening description of Toronto, for example, suggests that colonial legacies linger just below the surface of Canada’s urban sites, sites that are often celebrated for fostering diasporic transnational communities bound in resistant solidarity:

There are Italian neighbourhoods and Vietnamese neighbourhoods in this city; there are Chinese ones and Ukrainian ones and Pakistani ones and African ones…. All of them sit on Ojibway land, but hardly any of them know it or care because that genealogy is willfully untraceable except in the name of the city itself. They’d only have to look, though, but it could be that what they know hurts them already, and what if they found out something even more damaging? These are people who are used to the earth beneath them shifting, and they all want it to stop—and if that means they must pretend to know nothing, well, that’s the sacrifice they make. (4)

Discussion Questions

- This opening dismisses the idea that there is a clean separation between Canada’s colonial past and transnational present. Rather, colonial history and the ongoing occupation of Indigenous land diffuse under Canada’s white and non-white communities alike. What, according to the novel, are the consequences of ignoring—intentionally or passively—this historical and contemporary colonization?

- What issues does Brand’s novel suggest have yet to be settled between Canada’s Indigenous and diasporic communities? Thinking more expansively, does this introduction in any way help explain the novel’s shocking conclusion?

- Reflecting on Guyanese Canadian author Tessa McWatt’s novel Out of My Skin, Petra Fachinger argues that although the work “encourages readers to think critically about how racialized minorities are complicit in the colonization of Indigenous peoples in Canada and how issues of racial discrimination and exclusion experienced by African and Afro-Caribbean Canadians cannot be separated from colonial legacies that continue to affect Indigenous peoples, it hesitates to fully imagine the implications of such complicity”(88). Can a similar argument be made about Brand’s What We All Long For? Why or why not?

Other Primary Texts to Consider

- All Our Father’s Relations (祖根父脈) (2016) directed and produced by Alejandro Yoshizawa, and co-produced by Sarah Ling and Jordan Paterson

- Bent Box (2000) by Lee Maracle

- Burning Vision (2003) by Marie Clements

- A Chorus of Mushrooms (1994) by Hiromi Goto

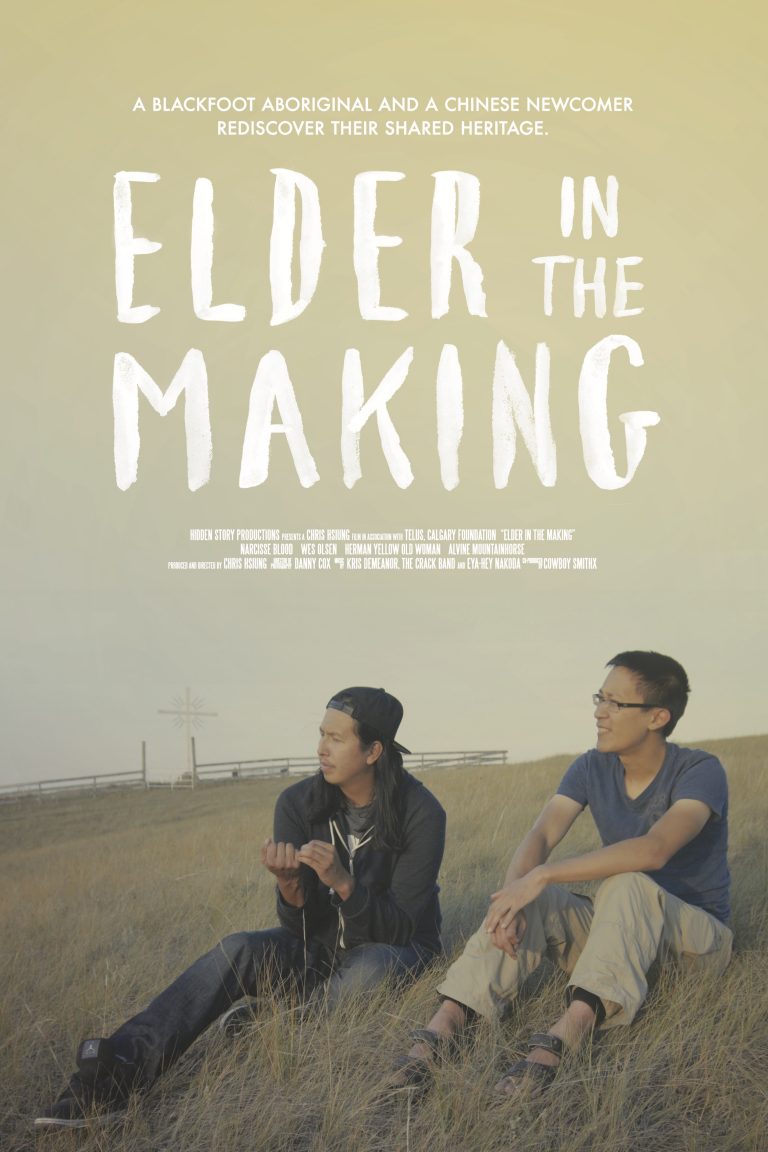

- Elder in the Making (2015) directed and produced by Chris Hsiung, and co-produced by Cowboy Smithx

- even this page is white (2016) by Vivek Shraya

- First Wives Club: Coast Salish Style (2010) by Lee Maracle

- The Outer Harbor (2014) by Wayde Compton

- Sundogs (1992) by Lee Maracle

- Sybil Unrest (2013) by Larissa Lai and Rita Wong

Works Cited

- Brand, Dionne. What We All Long For. Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2005. Print.

- Lee Maracle, “Yin Chin.” Native Writers and Canadian Literature. Spec. issue of Canadian Literature 124-25 (1990): 156-61. Print.

- Fachinger, Petra. “Intersections of Diaspora and Indigeneity: The Standoff at Kahnesatake in Lee Maracle’s Sundogs and Tessa McWatt’s Out of My Skin.” Tracking CanLit. Spec. issue of Canadian Literature 220 (2014): 74-91. Print.

- McWatt, Tessa. Out of My Skin. Toronto: Riverbank, 1998. Print.

©

©