This section offers two approaches for connecting Indigenous and diasporic texts, one that explores where these literatures share common ground, and one that is attuned to those places where they diverge.

The Margins as Common Ground: Race, Lost Homelands, and Belonging

In her sharply titled essay “Decolonizasian,” Rita Wong asks: “What happens if we position [I]ndigenous people’s struggles instead of normalized whiteness as the reference point through which we come to articulate our subjectivities?” Her “we” refers to Asian Canadians, specifically, and Canada’s more widely racialized communities, generally. Wong argues that Indigenous and diasporic communities share common concerns with land, belonging, language, and citizenship. In turn, these shared concerns are a basis for Indigenous and diasporic solidarity:

Through legislation such as the Indian Act, the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), the Multiculturalism Act, and the Citizenship Act, ‘we’ have historically been managed, divided, and scripted into the Canadian nation-state. Today ostensible security measures such as the Anti-Terrorism Act that passed in the wake of September 11th have given the state more power to criminalize indigenous peoples, activists, and people of colour. (159)

Wong’s contention is that experiences of racialization and common struggles for decolonization are a potential bridge between Indigenous and diasporic difference in Canada.

“A Black Canadian Woodcutter at Shelburne, Nova Scotia.” Watercolour sketch by William Booth, 1778. Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No 1970-188-1090 W.H. Coverdale Collection of Canadiana.

Another shared concern between diasporic and Indigenous scholarship involves temporality. Indigenous and diasporic communities are often problematically imagined as existing on opposite ends of Canada’s national timelines, with Indigenous peoples belonging only to Canada’s rural past, and racialized communities belonging only to Canada’s urban present. The result, as Lily Cho observes, is the erasure of Indigenous and diasporic communities from “Canadian” space. Interrogating these temporal and geographical narratives is one way literary scholars can bring Canada’s racialized migrant and Indigenous texts together.

Beyond Solidarity: Diaspora and Canada’s Settler-Colonial Present

Focusing on common struggles with racialization or non-recognition by the Canadian state is one way literary scholars can connect Indigenous and diasporic texts. That said, there are other difficult questions to consider when studying the literatures of these communities. One of these difficult questions has to do with what Wong describes as “immigrant complicity in the colonization of land” (Wong 158-59). Malissa Phung asks pointedly about these uncertainties: “If people of colour are settlers, then are they settlers in the same way that the French and British were originally settlers in Canada?” (292). How do racialized diasporas differ from the nation’s colonial settlers in their occupation of Indigenous land? When—or with whom—does Canada’s colonial history end?

Issues of nation, land, and identity entangle Indigenous, racialized-diasporic, and settler-invader communities in a simultaneously colonial and transnational Canada. Consequently, citizenship emerges as a concept that diaspora studies and Indigenous scholarship tend to disagree on. For example, Georges Erasmus, former national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, argues that there is no difference between racialized Canadians and Euro-Canadians. He explains, “The reason for this is simple. Aboriginal people have a unique historical relationship with the Crown, and the Crown represents all Canadians. From this it follows that all Canadians are treaty people” (vii). It is important to remember that many would argue the Crown has never represented all Canadians equally. Still, acknowledging this difference, Daniel Heath Justice contends that “the opportunities for non-Natives in Canada come as a consequence of the land loss, resource expropriation, social upheaval, and political repression of Aboriginal peoples” (145).

The recently published poetry collection by Indo-Canadian author Vivek Shraya, even this page is white, asks what it means to be aware of one’s own complicity in a national project that often disavows racialized Canadians:

is acknowledgement enough?

i acknowledge i stole this

but i am keeping it social justice

or social performance

what would it mean to digest you and yours and

blood and home and land and minerals and trees and dignities and legacies

to really honour no

show gratitude no

word for partaking in violence in progress. (li. 11-19, “indian”)

Shraya challenges her readers to think about what happens after acknowledging they occupy appropriated land. What happens after racialized and non-racialized Canadians acknowledge they are not leaving and cannot leave Canada? Her poem, titled “indian,” specifically asks how racialized-diasporic Canadians relate to the ongoing dispossession of Indigenous territory: “once my mother accidentally drove near a reserve / the only time I have seen her afraid hit gas pedal / strange to be indian and the sound of car locks / to be synonymous with indians” (li. 7-10). Shraya’s work challenges us to consider which desires are shared by Canada’s racialized diasporic and Indigenous communities, and which desires compete.

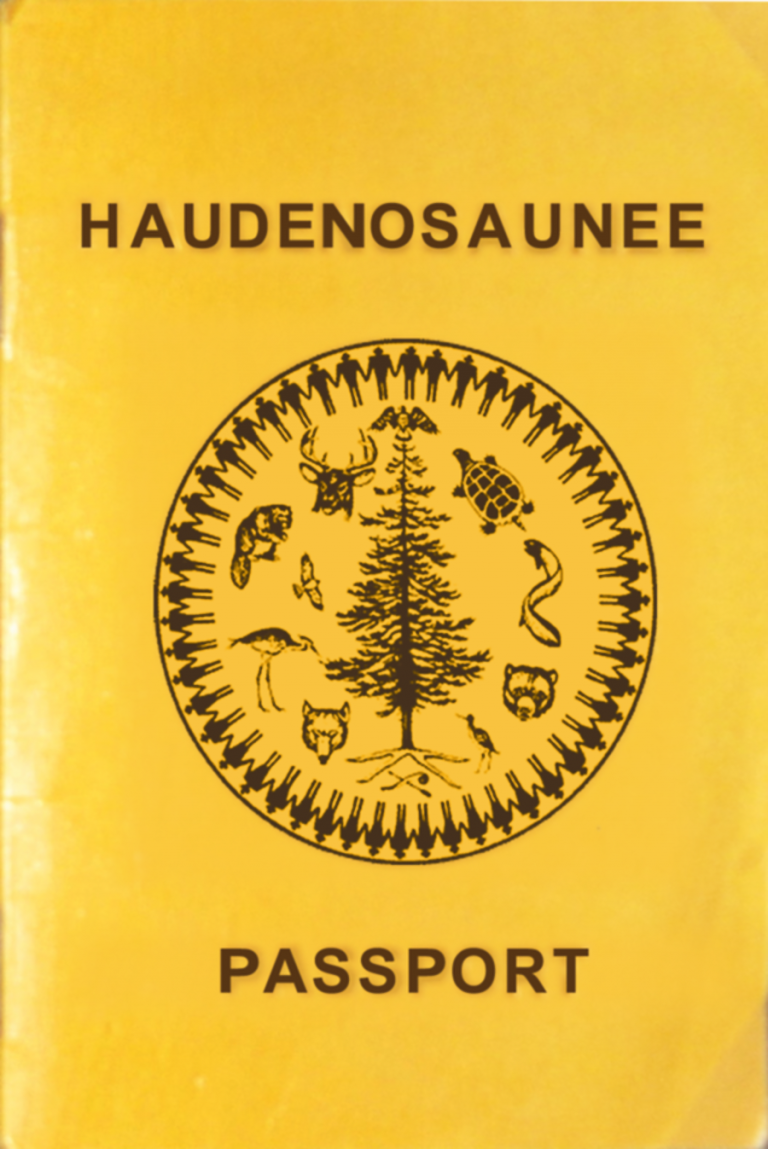

A Haudenosaunee League passport. Issued by the Haudenosaunee League since at least 1923, but not recognized by Canada as a valid documentation for international travel. Matthew G. Bisanz, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia.

Reflection Questions

- One way to stop seeing Indigenous and diasporic literatures as in opposition is to consider whether Indigenous literature is itself transnational. For example, can Indigenous communities be considered diasporic if their traditional homelands have been reimagined and appropriated?

- Do you agree with with Phung or Erasmus and Justice? Is there a difference between racialized and non-racialized Canadians’ occupation of Indigenous land? Why or why not?

- Returning to Erasmus’s quote, are all Canadians represented equally by the crown? Would an author like Dionne Brand agree with his logic?

Works Cited

- Cho, Lily. Eating Chinese: Culture on the Menu in Small Town Canada. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2010. Print.

- Erasmus, Georges. “Introduction.” Cultivating Canada: Reconciliation through the Lens of Cultural Diversity. Ed. Ashok Mathur, Jonathan Dewar, Mike DeGagné. Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2011: vii-x. Print.

- Justice, Daniel Heath. “The Necessity.” Movable Margins: The Shifting Spaces of Canadian Literature. Ed. Chelva Kanaganayakam. Toronto: TSAR, 2005: 143-59. Print.

- Phung, Malissa. “Are People of Colour Settlers Too?” Cultivating Canada: Reconciliation through the Lens of Cultural Diversity. Ed. Ashok Mathur, Jonathan Dewar, Mike DeGagné. Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2011: 291-98. Print.

- Shraya, Vivek. even this page is white. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp, 2016. Print.

- Wong, Rita. “Decolonizasian: Reading Asian and First Nations Relations in Literature.” Asian Canadian Studies. Spec. issue of Canadian Literature 199 (2008): 158-80. Print.

©

©