Loss of language

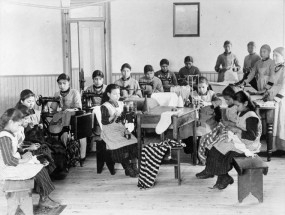

Sewing class in the residential school in Fort Resolution, N.W.T., date unknown. Canada. Dept. of Mines and Technical Surveys / Library and Archives Canada: PA-023095

Indigenous languages were seen as inferior, along with Indigenous cultures. Indian Residential Schools discouraged schoolchildren from speaking their languages; many children were physically punished for doing so. The objective of the residential schools was to assimilate the children into mainstream Canadian society. Residential schools taught English to assimilate children into Western ways, and to thereby eradicate, as Duncan Campbell Scott put it, “the Indian problem” (qtd. in Leslie 114). In Scott’s own words, the goals of the Residential school program were simple:

The happiest future for the Indian race is absorption into the general population, and this is the object of the policy of our government. The great forces of intermarriage and education will finally overcome the lingering traces of native custom and tradition. (qtd. in Monture 126)

The separation of children from their parents in order to destroy particular cultural and linguistic traditions is considered an act of genocide. The UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide states that “[f]orcibly transferring children” from one “national, ethnical, racial or religious group” to another is genocide if the transfer is done with the “intent to destroy, in whole or in part” the first group (Wikisource).

Residential school woodworking class, Kamloops, BC, 1958–59. Basil Fox / The Kamloops Sentinel. Library and Archives Canada: PA-185652

If the schools had taken proper care of the children and given them a good education, the legacy of Residential Schools may have been less devastating. However, the children were fed badly, often beaten and humiliated, sometimes assaulted sexually, kept from any contact with their family, and given an education that at best would fit them to be unskilled labourers or domestic servants. In response to this act of cultural genocide, Basil Johnston observes in his article “One Generation From Extinction” that

There is cause to lament but it is the native peoples who have the most cause to lament the passing of their languages. They lose not only the ability to express the simplest of daily sentiments and needs but they can no longer understand the ideas, concepts, insights, attitudes, rituals, ceremonies, institutions brought into being by their ancestors; and, having lost the power to understand, cannot sustain, enrich, or pass on their heritage. (10)

Thus, for Johnston, the loss of language promotes a loss of cultural understanding. To sustain and enrich Indigenous communities, Johnson contends, it is necessary to recover Indigenous language(s).

Indigenous Autobiography and Residential Schools

Main administrative building of the Kamloops Indian Residential School, 1970. Department of Citizenship and Immigration-Information Division / Library and Archives Canada: PA-185532

Many Indian residential school survivors published memoirs, including Basil Johnston’s Indian School Days (1988) and Bev Sellars’ They Called Me Number One: Secrets and Survival at an Indian Residential School (2012). Sometimes the survivors of particular schools collaborated to produce collective memoirs, such as Behind Closed Doors: Stories from the Kamloops Indian Residential School (2000), produced by the Secwepemc Cultural Education Society. For more information on specific residential schools, including lesson plans and useful links, see Indian Residential School Resources, run by the Indian Residential School Survivors’ Society. The websites of the churches who ran the schools, the United Church of Canada, the Presbyterian Church of Canada, the Anglican Church of Canada, and the Roman Catholic Church contain a variety of information on these schools as well.

Some writers have chosen to produce their memories as “autobiographical fiction,” a form of life writing that does not promise the fidelity to fact that autobiography does. Some fictional accounts are Robert Alexie’s Porcupines and China Dolls (2002), Tomson Highway’s Kiss of the Fur Queen (1998), Shirley Sterling’s My Name is Seepeetza (1992), and Richard Wagamese’s Indian Horse (2011).

As well, Indigenous peoples and scholars have done much work in recent decades to reverse the damage done by the residential school system. Many communities have initiated language revitalization projects, particularly by employing recording technologies, such as the First Voices initiative, to document and preserve languages spoken by only a few remaining Elders.

It is important to remember that there is a politics about what parts of life story are told in an autobiography. In her article “Unbecoming a ‘dirty savage,’” Linda Warley offers a helpful analysis of Jane Willis’ autobiography of her childhood, Geniesh (1973). Warley shows how difficult it was for Willis to overcome the complex ways that the school taught her to see her own body as dirty, diseased, and sexually dangerous. However, Warley shows how Willis resists being read as a stereotype, for example by using untranslated Cree in her narrative.

Truth and Reconciliation

In 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued an official apology and the government established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) to investigate and inform Canadians about what happened in residential schools. However, Margery Fee argues in her editorial to the Canadian Literature special issue Indigenous Focus that the TRC is just a beginning:

Although apologies are important, they are just the first step if the longstanding effects of racism and colonization are to be overcome at the human level. It seems paradoxical that reconciliation will be managed as a bureaucratic and state-run process, the same process that caused the problem in the first place. (8)

Over 70, 000 people participated in the Walk for Reconciliation in Vancouver on 22 Sept 2013, despite the downpour. Mike Borkent CC3.0

A difficulty with apologies is that they can end conversations rather than start them. A concern with the apology and the TRC is that they can imply that once they are completed the process of decolonizing Canada is over. Fee’s focus on the TRC as a first step in the process of reconciliation is consistent with the TRC mandate to engage in a process of national healing. The TRC mandate comes from “an emerging and compelling desire to put the events of the past behind us so that we can work towards a stronger and healthier future” (n.pag.). According to the TRC, such a process “will help set our spirits free and pave the way to reconciliation” (n.pag.). The TRC can be a step on the way to reconciliation, just as Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s apology was a step in the reconciliation process, but these steps will not end the process of reconciliation. Reconciliation is a long, historical process and the TRC is a solid and historically important foundation in the reconciliation process.

Works Cited

- Monture, Rick.

Essays on Canadian Writing 75 (2002): 118–41. Print.Beneath the British Flag

: Iroquois and Canadian Nationalism in the Work of Pauline Johnson and Duncan Campbell Scott. - Leslie, John . The Historical Development of the Indian Act. 2nd Ed. Ottawa: Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, 1978. Print.

- Warley, Linda.

Unbecoming a ‘dirty savage’: Jane Willis’s Geneish: An Indian Girlhood.

Canadian Literature 156 (1998): 83–103. Print. (PDF) - Johnston, Basil H.

One Generation From Extinction.

Canadian Literature 124–25 (1990): 10–15. Print. (PDF) - Fee, Margery. “The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.” Editorial. Canadian Literature 215 (2012): 6–10. Print.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Mandate. N.d. Web. 1 October 2013.

- United Nations General Assembly. “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.” 1948. Wikisource. 15 Jan. 2012. Web. 25 Sept. 2013.

- Willis, Jane Pachano. “Epilogue 2011.” Geniesh: An Indian Girlhood. Toronto: New Press, 1973. iPortal: Indigenous Studies Portal Research Tool. U of Saskatchewan Lib., n.d. Web. 25 Sept. 2013. (Link)

©

©