Nadine Fladd

This chapter introduces the short story as a literary genre, and discusses the short story cycle as a particularly important genre in Canada. It offers some suggestions for analyzing short stories from print culture and feminist perspectives, and it turns to Alice Munro’s 1978 short story cycle Who Do You Think You Are? as a case study in putting these perspectives to work.

What Is a Short Story?

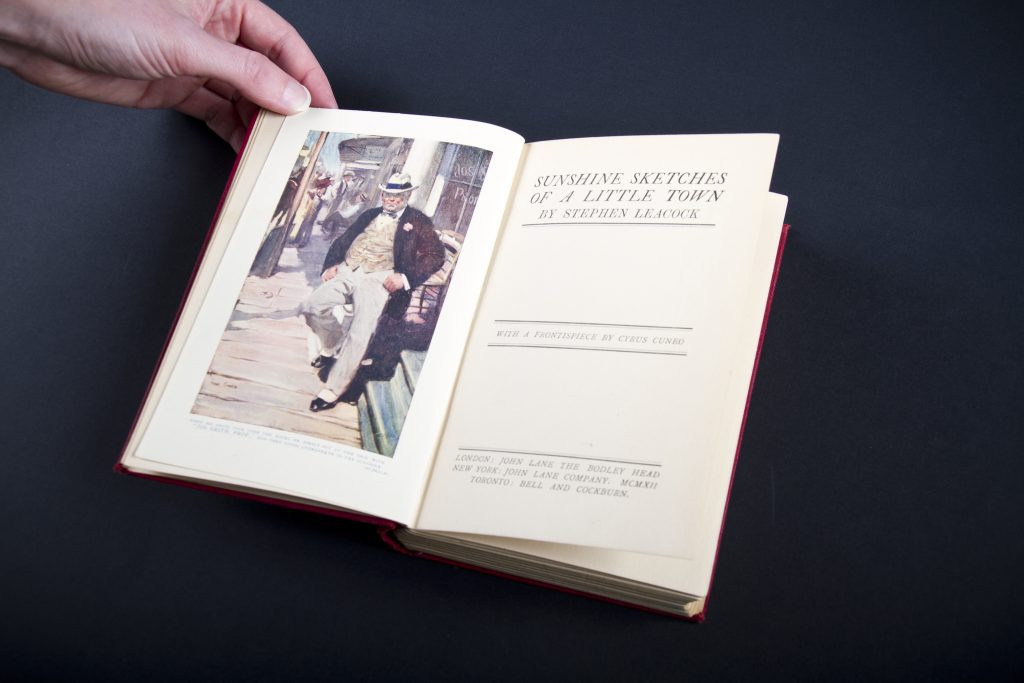

A 1912 copy of Stephen Leacock’s Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town. Library and Archives Canada, IMG_5945, CC BY-NC-NC 2.0, via Flickr.

The story is one of the oldest literary genres in the world. Icelandic storytellers, for example, used prose narratives called “Sagas” to recount events that took place in the ninth and tenth centuries, and eventually recorded these stories in writing. Yet when scholars of Canadian literature refer to “the short story,” they are referring to a very specific, newer genre. In the nineteenth century, as literacy rates increased in Europe and America, readers sought access to affordable leisure reading. At the same time, writers such as Anton Chekhov in Russia, Guy de Maupassant in France, and Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe in America began working on the short story: a genre that was often published in newspapers and could be read within a single sitting. In what would become Canada, author Thomas Chandler Haliburton first published his Clockmaker stories in serial form in the newspaper the Novascotian before collecting and publishing them as a book. The fact that such stories often first appeared in newspapers is one of the reasons literary critics like V. S. Pritchett have claimed that the short story is a “hybrid” genre that draws from both poetry and newspaper reporting (qtd. in Campbell 19). Canada’s well-known short story writers have included Alice Munro, Margaret Atwood, Mavis Gallant, Thomas King, André Alexis, Rohinton Mistry, Sheila Heti, Stephen Leacock, Clea Young, Lisa Moore, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Heather O’Neill, Carol Shields, Eden Robinson, Madeleine Thien, and countless others.

Elements of Short Fiction

What makes a short story a short story? Literary scholars Gerald Lynch and Angela Robbeson suggest short stories share “family features” such as “brevity, concision, [and] unity of impression and effect” (2). Nevertheless, what exactly counts as “short” has proven difficult to define. Some of the most compelling definitions of the short story have been written by short story writers themselves, who point out that the brief nature of the form requires them to carefully select and include individual details that encourage larger inferences about the story’s setting, character, or plot. In North America, Poe is often credited with first identifying and theorizing the short story; in his review of Hawthorne’s story collection Twice-Told Tales, he points out the “unity of effect” that he finds in each individual story. This “unity of effect” is heightened in the short stories published during the modernist era (the first half of the twentieth century), which often offer a snapshot of an individual character’s psychological state, or in which a character gains some significant insight (epiphany). Throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, critics from B. M. Éjxenbaum (81) to Charles E. May have suggested that a story’s ending or conclusion is an especially important element in the structure of short fiction, especially if it is an epiphanic one (May 300). The Irish author James Joyce is well known for concluding his short stories with these kinds of revelations, especially in his 1914 collection Dubliners, but we can also see this strategy being deployed in the work of several Canadian writers, including Joyce’s contemporary Morley Callaghan, as well as nineteenth-century author Duncan Campbell Scott and 2013 Nobel laureate Alice Munro.

The Short Story Cycle: an Important Canadian Genre

In both his book The One and the Many: English-Canadian Short Story Cycles and an earlier essay in Canadian Literature by the same name, literary critic Gerald Lynch explores not individual short stories, but collections of short stories by a single author that function as what he calls “cycles.” To be a short story cycle, a collection’s stories must be unified by either place or character (Lynch, The One 21). Stephen Leacock’s Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town (1912) and Duncan Campbell Scott’s In the Village of Viger (1896) are good examples of the first type: they contain stories that are all set within one small town or village, even though each story focuses on different characters who live within that community. In contrast, as Lynch points out, Alice Munro’s 1978 short story cycle Who Do You Think You Are? is an example of the second type. It consists of stories set in a variety of rural and urban Canadian settings, but each story is concerned with the development of one character in particular named Rose. Lynch suggests that the short story cycle, which occupies “the middle ground between short stories and novels,” functions as a particularly Canadian genre (The One 4).

Questions to Keep in Mind While Reading

- What similarities or differences have you noticed between short stories and other genres you have studied, such as poetry, novels, newspaper articles, comics, drama, or memes? Brainstorm a list of similarities and differences. Think about details related to form, content, and theme. Which of these similarities and differences do you think represent key elements of these genres?

- Imagine you are adapting your favourite film or novel into a short story. Plan out a rough outline for this adaptation. Will the ideas, themes, plots, characters, settings, or narrative perspectives of the novel or film need to change in order to fit this new form? In what ways?

- In The One and the Many: English Canadian Short Story Cycles, Gerald Lynch argues that the short story cycle is an especially popular mode for Canadian writers because it reflects the Canadian values of accommodation and compromise—of balancing the needs of the individual with the needs of the wider community. What do you make of this? Do you agree these are “Canadian values”? Can you identify ways in which formal aspects of the short story cycle reflect the values Lynch identifies?

Works Cited

- Campbell, Wanda. “Of Kings and Cabbages: Short Stories by Early Canadian Women.” Dominant Impressions: Essays on the Canadian Short Story. Ed. Gerald Lynch and Angela Arnold Robbeson. Ottawa: U of Ottawa P, 1999. 17-26. Print.

- Éjxenbaum, B. M. “O. Henry and the Theory of the Short Story.” The New Short Story Theories. Ed. Charles E. May. Athens: Ohio UP, 1994. 81-88. Print.

- Lynch, Gerald. “The One and the Many: English-Canadian Short Story Cycles.” Canadian Literature 130 (1991): 91-106. Print.

- —. The One and the Many: English-Canadian Short Story Cycles. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2001. Print

- Lynch, Gerald, and Angela Arnold Robbeson. “Introduction.” Dominant Impressions: Essays on the Canadian Short Story. Ed. Lynch and Robbeson. Ottawa: U of Ottawa P, 1999. 1-8. Print.

- May, Charles E. “The American Short Story in the Twenty-First Century.” Short Story Theories: A Twenty-First Century Perspective. Viorica Patea. New York: Rodopi, 2012. 299-324. Print.

- Poe, Edgar Allan. Rev. of Twice-Told Tales by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Short Story Theories. Ed. Charles E. May. Athens: Ohio UP, 1976. 45-51. Print.

©

©