The problematic concepts of (1) a dualism between civilization and savagery and of (2) progress informed the logic of European colonization and Canadian assimilation policies and societal developments. Isolating these concepts helps us better understand how these ideas inform various past and present social and cultural practices, including the writing and reading of literary texts.

Progress? The first atomic bomb test. The Atomic Energy Commission detonates the first thermonuclear device, code-named ‘Mike,’ at Enewetak Atoll in the Pacific. The device explodes with a yield of 10.4 megatons. 31 Oct. 1952. US Department of Energy

Métis critic Emma LaRocque calls the idea of a binary division between civilization and savagery the “Civ/Sav distinction” (15). This idea, perpetuated through generations of European thinkers, represents Europeans as the pinnacle of civilization, and any others—especially those they colonize—as their savage inferiors, thereby marginalizing their experiences and expressions in wider society. As literary historian Mary Lu MacDonald writes in Canadian Literature, “the assumption that Western European Christian civilization, with its accompanying ideals of progress and improvement, was the highest form of intelligent life” (93) underpins many other conversations about and literary representations of Indigenous peoples, in particular in early colonial works and society.

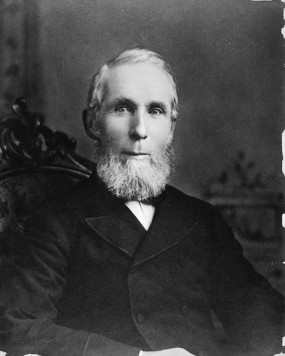

Alexander Mackenzie. Photographer and date unknown. Library and Archives Canada, accession number 1947-055 NPC, C-000096

The Civ/Sav distinction informs many early explorer narratives, such as those of famous Scottish explore Alexander Mackenzie. As Parker Duchemin argues in “‘A Parcel of Whelps’: Alexander Mackenzie among the Indians,” Mackenzie’s writings “played an important part in forming the public image of these [Indigenous] peoples, both in Canada and abroad, an image which continues even to the present time” (50). The Civ/Sav distinction colours Mackenzie’s representations of Indigenous peoples and his reports of his interactions with them. Mackenzie edits his experiences to reflect his own sense of superiority towards the Indigenous peoples, enacting “textual strategies of domination” (63) by suggesting that his guides are rebellious and mutinous because of their savage characteristics (58) while giving “no hints about their appearance, their private lives, or their character” (60), thereby diminishing their humanity.

While Mackenzie manipulates and threatens the Indigenous peoples he encounters into momentary cooperation, he assumes that he’s entitled to such actions and their lack of compliance is disrespectful. Through these strategies, as Duchemin argues, “Mackenzie ignores or trivializes almost everything which suggests that the Indians may have had a meaningful life beyond the merely physical level of their existence” (64). By enacting the Civ/Sav distinction in his popular writings, Mackenzie propagates a dehumanized view of Indigenous peoples and their cultural diversity.

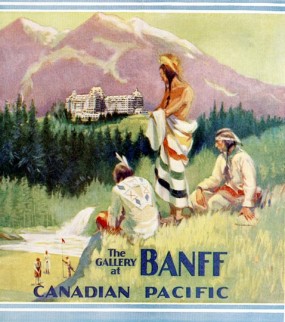

On the Green poster for Banff and the CPR (1930), reflecting a Eurocentric representation of three Indigenous figures. R.H. Palenske, Canadian Pacific Archives, BR15

The Civ/Sav distinction supported the marginalization of Indigenous peoples, placing them on the periphery as participants in mainstream society, which to a certain extent continues today. For instance, Karen Charleson, writing from a Hesquiaht First Nation perspective, analyzes the presence of the Civ/Sav distinction in journalist Margaret Horsfield’s popular history, Cougar Annie’s Garden (1999). In Charleson’s Canadian Literature article “Re-considering Margaret Horsfield’s Cougar Annie’s Garden,” Charleson aims to illustrate “the ways that white settler culture and knowledge comes to dominate the intellectual and physical landscape of Hesquiaht” (13).

Building on the work of Bruce Braun, Charleson sums up the troubling logic of progress and settler culture as such: “In order for the settler way of life to quickly predominate, traditional territories are viewed as wilderness, as devoid of humanity and culture” (25). She shows how the complex colonial beliefs of progress and the Civ/Sav distinction, predicated largely on Indigenous erasure, still inform contemporary society and writing. The popular success of Horsfield’s relatively recent book affirms it “as an example of continuing colonial domination, a continuing negation and denial of indigenous reality” (26). Thus, the logic of the Civ/Sav distinction, predicated on Western superiority and progress, continues to impact engagements with Indigenous peoples and their lands.

It is important to keep in mind this pervasive distinction when approaching works of literature that represent Indigenous peoples. As well, keep in mind that Indigenous writers often work to undermine or expose the harmful implications of the Civ/Sav distinction. Thomas King’s novel Green Grass, Running Water is an example of a novel that satirized Eurocentric understandings of history.

Works Cited

- Charleson, Karen.

Re-considering Margaret Horsfield’s Cougar Annie’s Garden.

Canadian Literature 197 (2008): 12–27. Print. - Duchemin, Parker.

Canadian Literature 124–25 (1990): 49–74. Print. (PDF)A Parcel of Whelps

: Alexander MacKenzie among the Indians. - King, Thomas. Green Grass, Running Water. Toronto: HarperCollins, 1993. Print.

- LaRocque, Emma. When the Other is Me: Native Resistance Discourse, 1850–1990. Winnipeg: U of Manitoba P, 2010. Print.

- MacDonald, Mary Lu.

Red & White Men; Black, White & Grey Hats: Literary Attitudes to the Interaction between European and Native Canadians in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century.

Canadian Literature 124–25 (1990): 92–111. Print. (PDF) - Horsfield, Margaret. Cougar Annie’s Garden. Nanaimo: Salal Books, 1999. Print.

©

©