Indigenous literatures in Canada emerge from a long history of colonization, a history that mainstream Canadian society has only just begun to understand. Throughout this colonization process, Indigenous communities were segregated, languages were eradicated, and traditions were outlawed. Despite these seemingly prohibitive obstacles, Indigenous writers published important works in the nineteenth century. The non-fictional conversion narratives of George Copway/Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh (1818–1869; Ojibway/Mississauga) and George Henry/Maungwudaus (1811–after 1855; Ojibway) were important foundational texts in Canadian literature. The political writings of Joseph Brant/Thayendanegea (1742–1807; Mohawk) and Métis leader Louis Riel (1844–1885) were also influential.

The first creative writer of Indigenous descent to break into mainstream European literary circles was E. Pauline Johnson/Tekahionwake (1861–1913). Her father, George Johnson, was a Mohawk chief. Her first public reading in 1892 led to great acclaim and she was included in early anthologies, but modernist poets later criticized her work as sentimental (see Fiamengo and Shrive). In her Canadian Literature article “‘The Most Canadian of all Canadian Poets’: Pauline Johnson and the Construction of a National Literature,” Carole Gerson writes about Johnson’s navigation and advocacy of Indigenous issues in the early 1900s and her influence on contemporary Indigenous writers.

Cover of Slash by Jeannette Armstrong. Used with permission from Theytus Books

Most Indigenous works of literature in Canada were published after Indigenous protests against the federal White Paper (1969) (see “The White Paper 1969”). Hartmut Lutz notes in his article “Canadian Native Literature and the Sixties” that the 1960s were “bread and butter” years for Canada’s Indigenous population, “both in the physical and in the ideological sense. Confronted with stifling conditions, Native people struggled hard to retain/reclaim their identity” (168). Part of this reclamation project involved reclaiming stories, both traditional stories and autobiography. Some trailblazing publications that emerged in the following years include two autobiographical works, Maria Campbell’s Halfbreed (1973) and Anthony Apapark Thrasher’s Thrasher … Skid Row Eskimo (1976), which brought personal experiences of colonization to mainstream readers. As Margery Fee argues in “Upsetting Fake Ideas,” two important and popular novels, Jeannette Armstrong’s Slash (1985) and Beatrice Culleton Mosionier’s In Search of April Raintree (1983), actively disrupted colonial assumptions in contemporary society to “expose the fake ideas and debunk the ‘choices’ that white acculturation has forced on Native peoples in Canada” (168).

As an illustration of the importance of telling stories about Indigenous peoples, we can look at the publication of non-Indigenous playwright George Ryga’s play The Ecstasy of Rita Joe (1967). Ryga’s play was one of the first dramatic works to address colonial history head on. The play was first performed at the Vancouver Playhouse on 23 November 1967 with an Indigenous cast, and was directed by George Bloomfield. The date of the staging is not a coincidence. 1967 was Canada’s centennial, and the play was commissioned as part of a project of rethinking Canada and its history and peoples. As Lutz notes, the play

… became a general consciousness-raiser, not only for white audiences, but for many Native persons as well, who for the first time witnessed how a sympathetic non-Native author addressed their situation in public. The play demonstrated that Native actors could successfully play on mainstream stages, and that urban Indians could, indeed, be “news.” For many young Native people[,] seeing Ryga’s play became an incentive in their struggle for their humanity. (174)

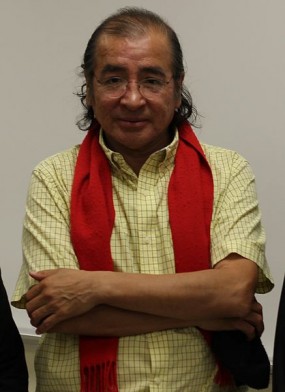

Tomson Highway, Oct 2011. Truelight 234 via Wikimedia Commons

It is hard to overstate the power of seeing Indigenous actors on stage depicting a story about Indigenous people in a major theater in Canada for the first time. This play, in many ways, also created a space for other, important, Canadian Indigenous dramatists like Tomson Highway, Marie Clement, and Daniel David Moses, as well as an entire generation of Indigenous actors, directors, and theatre companies.

The discomfort of learning how to listen to Indigenous stories about colonization should not be ignored, nor should the rewards of doing so. While Ryga’s play was certainly a powerful moment for Indigenous audience members who were, for the first time, seeing their history reflected on stage, the vast majority of the paying customers for such a run would have been non-Indigenous patrons, many of whom would have been ignorant of Canada’s colonial history and the plight of Canada’s Indigenous peoples. In a statement that may apply for all Canadian Indigenous fiction, Agnes Grant (1990) writes about Indigenous women writers,

Native literature often confronts readers with a history that is stark and unredeemable—because the historic treatment of Natives was callous. This may be a point of view unfamiliar to many non-Native readers. (125)

Although Ryga is a non-Indigenous author, he confronts his readers/viewers with a stark history that seems unredeemable and asks his audience to pay attention to that history in the hopes that such attention may lead to social and political change. The play’s focus on the hardships and tragedies of urban Indigenous peoples created, in some ways, a place for Indigenous and non-Indigenous critics to begin listening to the voices, aspirations, and hopes of a community that had been largely ignored on mainstream stages and in high literary culture.

After the success of Ryga’s play in 1990, many Indigenous Canadian writers have found publishing success. In 1993, Thomas King’s novel Green Grass, Running Water was nominated for the Governor General’s Award in Fiction—the first book written by an Indigenous author to receive the nod. A decade later, King also became the first person of Indigenous descent to deliver a CBC Massey Lecture. Another milestone was Eden Robinson’s Monkey Beach, which was nominated for the 2000 Governor General’s Award and The Giller Prize. The success of authors such as King and Robinson illustrates the increasing visibility of writing by Indigenous authors in Canada. Indigenous literatures are now taught at Canadian universities and academic journals like Canadian Literature regularly publish criticism on Indigenous writing, creating a sustainable scholarly conversation.

The relatively recent emergence of Indigenous literatures in Canada is due to connections between increased literacy and literary production, publishing opportunities (especially with Indigenous-owned publishers like Theytus and Kegedonce), critical reception, and changes in Canadian society. The rich diversity of contemporary Indigenous works raises many important questions. Some questions reflect issues regarding how Indigenous ways of being adapt colonial languages and practices to assert alternative perspectives, thereby disrupting dominant assumptions. Due to the diversity and plurality of Indigenous cultural heritages, the multiplicity of these understandings informs and opens up contemporary writing.

Works Cited

- Lutz, Hartmut.

Canadian Native Literature and the Sixties: A Historical and Bibliographical Survey.

Canadian Literature 152–53 (1997): 167–91. Print. (PDF) - Gerson, Carole.

Canadian Literature 158 (1998): 90–107. Print. (PDF)The Most Canadian of all Canadian Poets

: Pauline Johnson and the Construction of a National Literature. - Grant, Agnes.

Contemporary Native Women’s Voices in Literature.

Canadian Literature 124–25 (1990): 124–32. Print. (PDF) - Fee, Margery.

Upsetting Fake Ideas: Jeannette Armstrong’s

Canadian Literature 124–25 (1990): 168–80. Print. (PDF)Slash

and Beatrice Culleton’sIn Search of April Raintree.

- Ryga, George. The Ecstasy of Rita Joe. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1970. Print.

- Shrive, Norman.

What Happened to Pauline?

Canadian Literature 13 (1962): 25–38. Print. (PDF) The White Paper 1969.

Indigenous Foundations. First Nations Studies Program at [the] U of British Columbia, 2009. Web. 15 Aug. 2013. (Link)- Fiamengo, Janice Anne. The woman’s page: journalism and rhetoric in early Canada. Toronto: U Toronto P, 2008. Print.

©

©