Vancouver Pride, 2 Aug 2009. Pipistrula, CC 2.0, flickr

As part of the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics, Canada became the first country ever to host a Pride House as an official Olympic venue. The Vancouver Olympics were a major nation building project for Canada, and the events we hosted, and venues we supported, told the world a story about Canada and the kind of nation we would like to be. In this case, by having a Pride House, Canada told a story that gay pride was an important part of Canadian national identity. Pride House was a marker that Canada was an international leader on LGBTQ* issues.

Yet Canada did not become a world leader on LGBTQ* issues overnight. Instead, the process has been slow, painful, and intergenerational. Many of the major events in the story of Canada’s progress on LGBTQ* issues happened at the Parliamentary and Supreme Court level, but such change could not have happened without activism by Canadians. As Miriam Catherine Smith argues in Lesbian and Gay Rights in Canada, an important part of the story of the gradual improvement of LGBTQ* rights in Canada is “the constitutional entrenchment of the bill of rights and the attendant increase in the judiciary’s capacity to police equality issues” (4). As Smith further notes, while community activism has always been an important part of the LGBTQ* movement, it has from its inception “addressed itself at least in part to the state” (10). Sylvain Larocque, in his study of marriage equality in Canada, notes that while homophobia is still widespread in Canada, “dramatic progress has been made in recognizing their rights over the last 30 years, and especially in the last decade” (12). Changes to Canadian laws around LGBTQ* peoples are important, but the fact that these laws needed to be changed in the first place highlights the implicit heteronormativity of Canadian law.

As Tom Warner argues in Never Going Back, an issue with incremental legal changes is that they do not address the underlying homophobia in the Canadian cultural identity:

Changing a few laws and achieving tolerance are necessary, but insufficient in themselves to achieve fundamental social change. Lesbian and gay liberation means coming to a positive consciousness of oneself and other gays and lesbians. It requires a personal transformation based on an understanding that gays and lesbians are taught by our society in various ways, both subtle and blatant, to hate and thereby oppress themselves. (8)

Internalized homophobia can lead LGBTQ* people to think that their desire makes them somehow not fully persons within Canadian society. As Kathleen A. Lahey argues in Are We ‘persons’ Yet?, the Canadian state has made many members of the LGBTQ* community feel as if they are not fully citizens of the state, and one of the ways that LGBTQ* community demand full personhood is through legal challenges:

Along with growing numbers of sexual minorities around the world, lesbian, bisexual, gay, transgendered, transvestite, and transsexual people in Canada have concluded that they have need to seek the assistance of the legal system in order to disrupt the vast systems of official homophobia and heterosexual privilege built into the foundations of Canadian culture. (4)

Heterosexual privilege is the idea that heterosexual peoples have privileges in Canadian culture and law because their desire is seen as normative. Heterosexuals do not need to justify their desire, their right to marry the person that they love, or to have and raise children.

One of the places where heterosexual privilege is most pervasive is in discussions of literature by and about the LGBTQ* community. For a good primer on heterosexual privilege, see M. Rochlin’s “The Heterosexual Questionnaire.” Consider, for example, the way that the first three questions Rochlin asks flips the discourse of assumed heterosexuality around:

1. What do you think caused your heterosexuality?

2. When and how did you first decide you were a heterosexual?

3. Is it possible that your heterosexuality is just a phase you may grow out of? (95)

Question three is a particularly troubling, and yet frequent, question asked of university-aged LGBTQ* people. Asking someone if they will grow out of being a homosexual implies that fully functioning adults are, by default, heterosexual, and that homosexuality is a flaw or retardation in social and sexual development. It equates homosexuality with immaturity and, in turn, becoming a heterosexual with becoming an adult. While many of us think nothing of asking a gay person or author questions about the cause, origin, and permanence of their homosexuality, flipping the questions allows us to see just how absurd questioning heterosexuality seems. Why don’t we view questioning homosexuality as equally absurd? This issue comes up frequently in literary analysis in the discussion of queer characters. Consider how common it is to look for the cause of a character’s homosexuality while we, at the same time, never ask if the heterosexuality of a character is caused, if it has an origin story, and if it is possible that the character will just grow out of being a heterosexual.

Works by heterosexuals, and heterosexual men in particular, are discussed as if they reflect a universal, Canadian, perspective, while the work of LGBTQ* authors are frequently read as representing only a minority, divergent perspective. LGBTQ* characters, when they appear at all, are treated as if they queerness is their defining characteristic. Changes to Canadian law will not break down heterosexual privilege, but such changes are, as Warner notes, essential first steps for recognizing LGBTQ* persons as full persons within Canada.

LGBTQ* Legal History in Canada

Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Affiche de Pierre Elliott Trudeau. 1968. Library and Archives Canada, acc. no. R11473-14, C-151890

The story of the struggle for LGBTQ* rights in Canada is one of incremental political and social changes. In 1953 the Canadian government passed an amendment to the Canadian Immigration Act, effectively banning gay men and women from immigrating to Canada. This amendment stayed in effect until 1978. In 1969 Canada amended the Criminal Code to decriminalize sexual practices like sodomy and gross indecency, allowing consenting adults to have homosexual sex. With this change in law came the quintessentially Canadian understanding that, as Prime Minister Elliott Trudeau put it in a scrum interview in 1967, “there’s no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation.” Trudeau’s point was that the state ought not to legislate sexual morality. Consenting Canadian adults should have the right to love, and have consensual sex with, whomever they want.

Paul Martin in 2006. Kate Gotti, CC 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The fight for marriage equality and equal rights in Canada is long and complicated. In 2000, the Canadian government effectively legalized marriage equality. On 28 June 2005, Prime Minister Paul Martin’s government passed Bill C-38, redefining marriage as a union between two people; the law received royal assent on 20 July 2005. On 7 December 2006 a bill by Stephen Harper’s Conservative Government to reopen the same-sex marriage debate in Canada was defeated, ending the discussion around marriage equality in Canada. There are, however, still cultural and religious groups who strongly oppose marriage equality in Canada and there is a long way to go before the LGBTQ* community obtains full equality within Canada and there is an end to homophobia.

Homophobia and Canadian Literary Reception

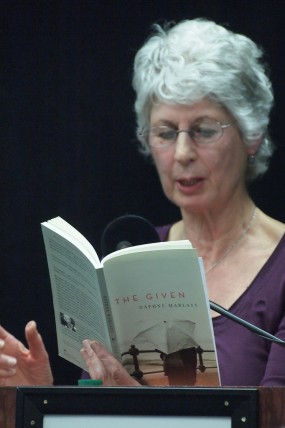

Daphne Marlatt. Daphne Malatt at Tree Nov 17, 2012. by pesbo CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

As these changes in LGBTQ* rights happen within Canada, there are a growing number of queer identified writers including Daryl Hine, Timothy Findley, Betsy Warland, Dionne Brand, Tomson Highway, Ann-Marie MacDonald, Daphne Marlatt, and Shyam Selvadurai. While LGBTQ* writers are still marginal to the Canadian literature canon, there is an ever-growing critical mass of authors working on queer issues, and literature scholars within Canada have begun what some scholars are calling a turn to sexuality within Canadian literature. This turn is making questions about sexual identity, gender, and desire within texts central to the study of literature and culture.

Historically, homophobia has impacted the reception of LGBTQ* writers, especially when their work addresses queer themes and same-sex desire. Consider, for example, Susan Sheridan’s discussion of Jane Rule’s reception in Canadian Literature. According to Sheridan, lesbianism was central to Rule’s writing and clouded her critical reception:

…from her first published novel onwards, lesbian experience was central, though not exclusive, concern of [Rule’s] fictional world. She was one of the first writers of serious realist fiction to address love between women directly, and sign her own name to it. Indeed, she might have welcomed some degree of separation, on the part of critics, between their attitudes to her subject matter and their judgments of her art: when her first novel, Desert of the Heart, was published in 1964, reviewers took it upon themselves to chide her for choosing a socially unacceptable subject, while colleagues at the University of British Columbia were only persuaded to reappoint her as a teacher by the argument that if writers of murder mysteries were not necessarily murderers, then writers of lesbian fiction were not necessarily lesbians. (15)

Where refusing to reappoint someone on the basis of their sexual identity is now a crime, implicit in Sheridan’s reading of the actions of UBC is the idea that Rule had to prove that she was not necessarily a lesbian in order to remain a teacher at UBC. Signing her own name to a work that features lesbian themes was a particularly brave thing for Rule to do because doing so had potential economic consequences.

Rule was not alone in facing consequences for her literary reception because she wrote about queer themes. Stephen Guy-Bray, in his discussion in Canadian Literature of Canadian poet and translator Daryl Hine, notes that a “latent homophobia” in the Canadian literary establishment impacted Hine’s reception (75). The establishment found the references to homosexuality in Hine’s works inaccessible and, as such, argued that a properly Canadian work of poetry would avoid inaccessible homosexual themes. Heterosexual privilege is about knowing that writing about heterosexual desire will not have economic consequences; in fact, writing about heterosexual desire can actually enhance the sales of a book. In contrast, not only can writing about LGBTQ* desire limit the market for a writer’s works, it can have further economic, social, and political consequences.

General Questions for Literary Analysis

The impact of LGBTQ* writers, activists, and theorists on the study of English is diverse, and one of the things that has changed in the field is that we ask new questions about texts by queer identified, and non-queer identified, writers. Some of the questions gender theorists like to ask about literature include ones about privacy, desire, heteronormativity, and sexual preferences.

- Privacy: Consider the notion of coming out as a spatial idea and a social idea. How might space in the text be associated with privacy and secrecy or openness and freedom? How does gender and sexuality operate in the various spaces of the text, and how is this tied to characterization?

- Desire: How is desire represented in the text? How is attraction between men, or between women, represented? Is such desire seen as normative or as divergent?

- Heteronormativity: How does the text address societal norms about gender or sexuality? Is being queer shown as a divergent form of sexual identity, or is heterosexuality the implicit norm?

- Sexual Preference: How is sexual preference characterized in the text? What values are ascribed to sexual preference and who has the power to ascribe these values?

Works Cited

- Guy-Bray, Stephen.

Daryl Hine at the Beach.

Canadian Literature 159 (1998): 74–88. Print. - Lahey, Kathleen A. Are We ‘persons’ Yet?: Law and Sexuality in Canada. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1999. Print.

- Larocque, Sylvain. Gay Marriage: The Story of a Canadian Social Revolution. Trans. Robert Chodos, Benjamin Waterhouse, and Louisa Blair. Toronto: J. Lorimer, 2006. Print.

- Rochlin, M. “The Heterosexual Questionnaire.” Privilege: A Reader. 2nd ed. Ed. Michael S. Kimmel and Abby L. Ferber. Boulder: Westview, 2010. 95–97. Print.

- Smith, Miriam C. Lesbian and Gay Rights in Canada: Social Movements and Equality-Seeking: 1971-1995. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1999. Print.

- Warner, Tom. Never Going Back: A History of Queer Activism in Canada. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2002. Print.

©

©