Ceilidh Hart

The book tends to get a great deal of focus in contemporary Canadian literary culture: literary awards, national reading programs such as Canada Reads, university courses, even, tend to place the book at the centre. And yet, in the nineteenth century, it was the periodical press—magazines and newspapers—that drove Canada’s cultural life. This chapter, using the writing career of Isabella Valancy Crawford as a case study, explores the importance to readers and writers alike of periodical publishing in early Canada, and the profound role it played in shaping a national literary culture at that time.

After being established first in the Atlantic region in the 1700s, by 1840 the periodical press was widespread across Canada. Although they shared many features of today’s magazines and newspapers, early periodicals were unique in that they offered readers substantial literary material, including poetry, short stories, serialized novels, and even comics. This was true not only of literary magazines whose purpose was directly entertainment and intellectual pursuit, but also of the daily newspaper, which became the chief source of reading material for most families, even when compared with the public library. Newspapers—and the literature within—became especially accessible in the latter half of the nineteenth century as prices dropped and the content was increasingly tailored to the working class.

Front page of The Globe, December 2, 1845. via Wikipedia.

By the 1880s, a typical reader had access to several large city papers, dozens of smaller papers published and circulated by religious presses, student associations, and special interest groups, as well as any number of magazines, all of them playing an active role in promoting literature—and literacy—across the country. Importantly, while these newspapers and magazines borrowed much of their content from Europe and the US, they also worked to include local, original content, building both reading and writing communities that were unique to Canada.

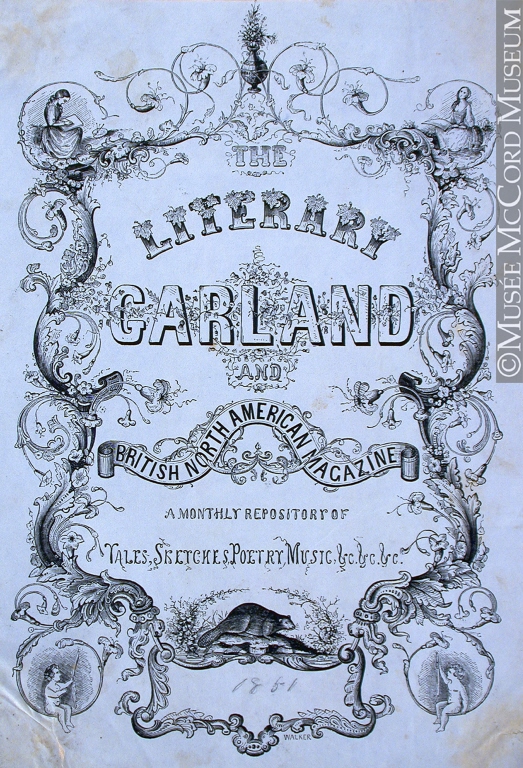

And in fact, the importance of newspapers and magazines for readers in early Canada is mirrored in the significant role they played for writers. The periodical press was the primary publishing venue for creative writers in nineteenth-century Canada. Indeed, many canonical works that we typically study as books began as periodical publications. For example, the sketches for Susanna Moodie’s Roughing It in the Bush (1852) were first published in the Montreal-based Literary Garland and The Victoria Magazine, published out of Belleville. Given the prohibitive cost of monograph—or book—publishing, writers turned to the periodical press to help establish their reputations and build audiences, and to receive some remuneration as they did so. Books may have offered prestige, but periodical publishing more consistently offered pay (Gerson 69), and so writers wanting to make a living from their literary endeavours—especially writers marginalized in terms of power and privilege—turned to this form of publishing.

Like authorship itself, periodical publishing was a precarious business, and there are far more stories of failed publishing ventures than successful ones; however, a few publications stand out for their longevity and their lasting influence on Canadian culture. The Literary Garland, which ran from 1838 until 1851, and the Toronto newspaper The Globe, founded in 1844 (and still published today as The Globe and Mail), are two good examples. In the pages of these and other publications appeared the work of some of Canada’s most important nineteenth-century writers: Susanna Moodie, E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake), Thomas Chandler Haliburton, Isabella Valancy Crawford, Rosanna Leprohon, John Richardson, Bliss Carman, Archibald Lampman, and many others. Literary historian Merrill Distad reminds us that “[a]t their best, [early Canadian periodicals] represented an earnest effort to promote Canadian writers and artists, provided a showcase for their work, and developed the cultural dimension of an emerging national identity” (299).

Questions to Keep in Mind While Reading

- As noted above, in the nineteenth century, book publishing may have offered prestige, but periodical publishing more consistently offered pay (Gerson 69). How does this binary (art-for-art vs. art-for-pay) influence literary cultures today? Is good literature necessarily at odds with profitable literature? Who decides what good literature is? How do the economics of writing and publishing influence different authors in unique ways?

- Cheap and accessible newspapers were at the forefront of expanding literacy in Canada. To what extent are reading communities and literary cultures shaped by issues of access? How have the Internet and the digital world changed the way we access literature and shaped how or what we read?

- Merrill Distad and others suggest that early newspapers and magazines helped establish a Canadian national identity. As you read examples of these early publications, how would you characterize early Canadian literature? Can you identify trends, tropes, or cultural interests that remain current?

- As Mary Lu MacDonald shows in “‘A Very Laudable Effort:’ Standards of Literary Excellence in Early Nineteenth Century Canada,” early readers and critics in Canada evaluated literature according to different criteria than they do today. Do you think our expectations for literature have changed over time? How so?

- How much does print context matter when we read a literary text? Do you expect something different from literature published in a magazine as opposed to a book?

- Where do you get your literature from? How do you find out about new writers or books or magazines? What do you think are the implications of using these as your sources?

Works Cited

- Distad, Merrill. “Newspapers and Magazines.” History of the Book in Canada. Vol. 2. Ed. Yvan Lamonde, Patricia Lockhart Fleming, and Fiona A. Black. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2005. 294-303. Print.

- Gerson, Carole. Canadian Women in Print, 1750-1918. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2010. Print.

- MacDonald, Mary Lu. “’A Very Laudable Effort’: Standards of Literary Excellence in Early Nineteenth Century Canada.” Canadian Literature 131 (1991): 84-99. Print.

©

©