Land disputes, legislative challenges, and other societal pressures have prompted the increasing expression of Indigenous national sovereignty across North America. As Cherokee writer Daniel Heath Justice argues,

Indigenous nationhood is more than simple political independence or the exercise of distinctive cultural identity; it is also an understanding of a common social interdependence within the community, the tribal web of kinship rights and responsibilities that link the People, the land, and the cosmos together in an ongoing and dynamic system of mutually affecting relationships. (24)

One result of Indigenous nationalism and the growing presence of Indigenous writers is the Native American-led call for Indigenous literary nationalism. This movement develops Indigenous-centred literary scholarship, promoted by Indigenous literary scholars and writers in Canada such as Jeannette C. Armstrong, Daniel David Moses, Daniel Heath Justice, Kristina Fagan, and Deanna Reder (see Fagan).

Vancouver First Nations Exhibition, 23 June 2008. Philippe Giabbanelli, 2008, via Wikimedia Commons

Agnes Grant asserts in her article Contemporary Native Women’s Voices in Literature,

that Native literature should be judged on its own terms and “not within a European paradigm” (126). Similarly, June Scudeler argues for this perspective because it grounds criticism in “the communities’ ways of knowing and traditions from which the work grew” (177). For example, Looking at the Words of Our People (1993), edited by Jeannette C. Armstrong, is a milestone in Indigenous literary nationalism, since it collects criticism by Indigenous scholars and is published by Theytus, an Indigenous publisher.

In his Canadian Literature article Epistemic Justice, CanLit, and the Politics of Respect,

Daniel Coleman affirms the importance of this recent shift from what Charles Taylor famously described as the politics of recognition—which assimilates different perspectives into established, familiar, and comfortable (post-Enlightenment European) critical frameworks—to a politics of respect, which seeks to meet people with different perspectives on their own grounds.

Coleman summarizes Stó:lo writer Lee Maracle’s explanation that “respect for the object of study requires a certain amount of distance, so that what we study is not alienated from its own context and turned into an acquisition of the learner” (125–26). Coleman goes on to observe that “[with] the remarkable resonance of Indigenous thought in the northern half of Turtle Island, the conceptual tools for transforming our ways of thinking are more readily available than they ever have been before” (125).

“A new and accvrat map of the world,” by John Speed, 1626. Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, CC 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Literary nationalism promotes the articulation of specific cultural traditions and ways of knowing that inform a particular author’s work. This doesn’t disregard the reality that writers write and publish for people beyond their nation, but asserts that engagement with their work should be as culturally specific as possible.

Thus, Armstrong argues that Indigenous literature “is in a position to influence the shape of Canadian literature ghettoized by old world and colonial literary standards” (184) because Aboriginal voices “support the reconstruction of a new order of internal culture and a relationship that transcends colonial thought and practice” (183). It achieves this influence by reconstructing representational practices of mass culture and society with specific Indigenous ways of knowing, thereby enacting Chief Dan George’s 1967 vision of adaptation and resurgence.

Literary Reconstruction

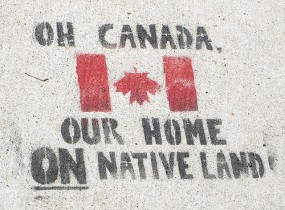

Stencil art on a sidewalk between a museum and a land registry office and court house in London, Ontario, on 16 Aug 2008. Toban Black, CC 2.0 via Flickr

Contemporary Indigenous writers employ a range of strategies to voice their unique stories and understandings. The diversity of expressive forms affirms the challenge Barbara Godard makes in her article The Politics of Representation: Some Native Canadian Women Writers

to non-Indigenous literary institutions about how we define and who gets to define the appropriate form of language and literature. The challenge stems from Indigenous critics Daniel David Moses’ and Lenore Keeshig-Tobias’ 1989 question, “Whose Story is it Anyway?” (Godard 185). Their challenges remain salient today.

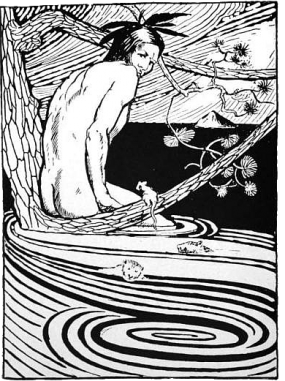

Some Indigenous writers incorporate their Nation’s language into works that are predominantly written in English. For example, Tomson Highway offers whole passages of Cree conversation in his play, The Rez Sisters. (For more on Cree literature, see the articles by Mareike Neuhaus and Angela Van Essen in Canadian Literature #215 (2012). Likewise, writers might include important cultural figures or narratives—such as Trickster and Creation figures like Raven, Coyote, Gluskeb, Nanabush or Sky Woman (see Fagan; Fee).

Other Indigenous writers subtly employ alterations of grammatical and stylistic conventions to suggest different perspectives on language and its speakers. These stylistic alterations may reflect storytelling traditions, language differences, as well as a diverse set of personal experiences (see Fiamengo, Godard, Grant).

“Manabozho [Nanabush] in the flood” (1905): a mythical Anishnaabe figure. By non-Indigenous anthropologist, R.C. Armour, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Hearing Stories

Indigenous stories may be provocative and unsettling to many readers, yet they present opportunities, as all good stories do, to question and re-conceptualize various understandings of community and identity. Thomas King, at the end of each chapter in The Truth About Stories, repeatedly encourages readers and listeners to “take it … [do] with it what you will … But don’t say in the years to come that you would have lived your life differently if only you had heard this story. You’ve heard it now.”

King presents a significant challenge since, as W. H. New affirms in his editorial for Canadian Literature’s special issue Native Writers & Canadian Writing, “[n]o one who does not listen learns to hear” (4). But here’s an important caution as well: with a long history of Eurocentric misrepresentation, reinterpretation, commodification, and marginalization, one must be careful to respect specific contexts and subtexts of Indigenous writings, so that in hearing and taking up Indigenous perspectives, one avoids repeating this history of appropriation.

Works Cited

- Armstrong, Jeannette C.

Aboriginal Literatures: A Distinctive Genre within Canadian Literature.

Hidden in Plain Sight: Aboriginal Contributions to Canada and Canadian Identity. Ed. David Newhouse, Cora Voyageur, and Dan Beavon. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2005. 180–86. Print. - Coleman, Daniel.

Epistemic Justice, CanLit, and the Politics of Respect.

Canadian Literature 204 (2010): 124–26. Print. (Link) - Essen, Angela Van. “nêhiyawaskiy (cree land) and Canada: Location, Language, and Borders in Tomson Highway’s Kiss of the Fur Queen.” Canadian Literature 215 (2013): 104–18. Print.

- Fagan, Kristina.

What’s the Trouble with the Trickster? An Introduction.

Troubling Tricksters: Revisioning Critical Conversations. Eds. Deanna Reder and Linda M. Morra. Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier UP, 2010. 3–20. Print. - Fee, Margery, and Jane Flick.

Coyote Pedagogy: Knowing Where the Borders Are in Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.

Canadian Literature 161–62 (1999): 131–39. Print. (PDF) - Fee, Margery.

The Trickster Moment, Cultural Appropriation, and the Liberal Imagination in Canada.

Troubling Tricksters: Revisioning Critical Conversations. Ed. Deanna Reder and Linda M. Morra. Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier UP, 2010. 59–76. Print. - Fiamengo, Janice.

Reconsidering Pauline.

Canadian Literature 167 (2000): 174–76. Print. - Godard, Barbara.

The Politics of Representation: Some Native Canadian Women Writers.

Canadian Literature 124–25 (1990): 183–225. Print. (PDF) - Grant, Agnes.

Contemporary Native Women’s Voices in Literature.

Canadian Literature 124–25 (1990): 124–32. Print. (PDF) - Justice, Daniel Heath. Our Fire Survives the Storm: A Cherokee Literary History. Minneapolis: U Minnesota P, 2006. Print.

- King, Thomas. The Truth about Stories: A Native Narrative. Toronto: Anansi, 2003. Print.

- Neuhaus, Mareike.

Towards a Relational Prairie Criticism: Louise Bernice Halfe and

Canadian Literature 215 (2013): 86–102. Print.Spacious Creation

. - New, W. H.

Learning to Listen.

Editorial. Canadian Literature 124–25 (1990): 4–8. Print. (PDF) - Scudeler, June.

Updating the Trickster.

Rev. of Troubling Tricksters: Revisioning Critical Conversations. Ed. Linda M. Morra and Deanna Reder. Canadian Literature 212 (2012): 177–78. Print. (Link) - Van Camp, Richard.

An Interview with Richard Van Camp (December 2008).

By Jordan Wilson. canlit.ca. Canadian Literature, n.d. Web. 15 Aug. 2012. (Link)

©

©