Ana Historic by Daphne Marlatt

Influenced by both avant-garde poetry and Virginia Woolf’s stream of consciousness narrative mode, Daphne Marlatt’s Ana Historic follows the mind of the narrator, Annie, at work. While researching the history of Mrs. Richards, a mysterious woman who appears in the civic archives of Vancouver in 1873, Annie’s mind jumps from her research to her personal struggle with her mother’s suicide, intermingling the three women’s stories on the page. The layout and typography change as perspective shifts, offering a collage of the women’s lives, serving as analogues to one another.

Roughing It in the Bush by Susanna Moodie

This popular account of emigration from England and settlement in Upper Canada has become a classic in the history of Canadian literature. First published in 1852, Roughing It in the Bush describes Susanna Moodie’s impressions of the people, places, and processes of settlement in the first seven years after she arrived in Upper Canada in 1832.

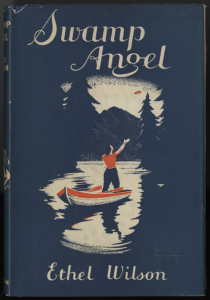

Swamp Angel by Ethel Wilson

Considered one of Wilson’s most accomplished works, Swamp Angelfollows Maggie Vardoe (later Lloyd) as she flees her husband in Vancouver to help run a fishing lodge in the interior of British Columbia. The novel illustrates the tension between her personal autonomy as a woman, and the needs and perceptions of a largely heteronormative community. Through the transformations of the main character, we can observe a process of attaining personal agency and self-actualization in the midst of societal constraints.

Poetry and Racialization

This chapter stages an imaginary conversation between Duncan Campbell Scott (born 1862), the Canadian Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932, and E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake; born 1861), the daughter of a Mohawk Chief and an Englishwoman. Scott and Johnson were distinctively different poets who addressed Indigenous issues from very different racialized and gendered perspectives.

Reading Visual Poetry

Some poets push further, beyond visual placement of words, to visual disruption of language itself. For example non-semantic or asemic visual poetry plays with letters in a variety of ways without forming words.

Close Reading Poetry

Think of close reading as similar to a criminal investigation in which we, as readers, move slowly through the language and forms of the text, working through suggested connotations, subtle connections, and implications of terms and images. Our goal is to unravel the subtle riches of expression, to solve (or glimpse) the mystery.

Close Reading Prose

The goal of a close reading is to produce a convincing and thorough interpretation of a text. Even straightforward prose can contain a trove of literary devices and strategies to either guide the reader toward meaning or obfuscate meaning altogether. While close reading, it is not only important to understand what authors are saying, but also, how they are saying it.

Close Reading Journal Articles

Academic articles are scholarly conversations. They often reference and speak to each other and allow scholars to acknowledge, criticize, engage, learn from, disagree with, and add to each other’s ideas. This conversation happens between peers with a shared language, knowledge base, and training.

Poetic Visuality and Experimentation

Literature loves to throw curveballs. Contemporary writers in particular often challenge expectations and assumptions about literature by purposefully disrupting them. Wynne Francis, writing on the 1960s literary scene, observes that Canadian literature became polarized between a mass market/mainstream culture (figured as the centre, or as culture itself) and the radical fringe that expressed a counter-culture of extreme experimentalism.

©

©