Despite her considerable media presence and the popularity of her texts, particularly the early ones, Seton-Thompson’s literary reputation has been rather overlooked in contemporary scholarship. This is partly due to the difficulty in categorizing Seton-Thompson according to nationality. A great deal of literary analysis has been done on her husband, and while she is often mentioned briefly in such work, her own life and writing have only started to be meaningfully discussed. Nevertheless, there are a number of theoretical lenses through which we might explore A Woman Tenderfoot. This section introduces readers to four possible topics or entry-points to her work: the new woman; imperialism and nationalism; the representation of Indigenous peoples; and feminism and performance. Keep in mind that these approaches may overlap. You will notice, for example, that the issue of gender informs many of them.

The New Woman in A Woman Tenderfoot

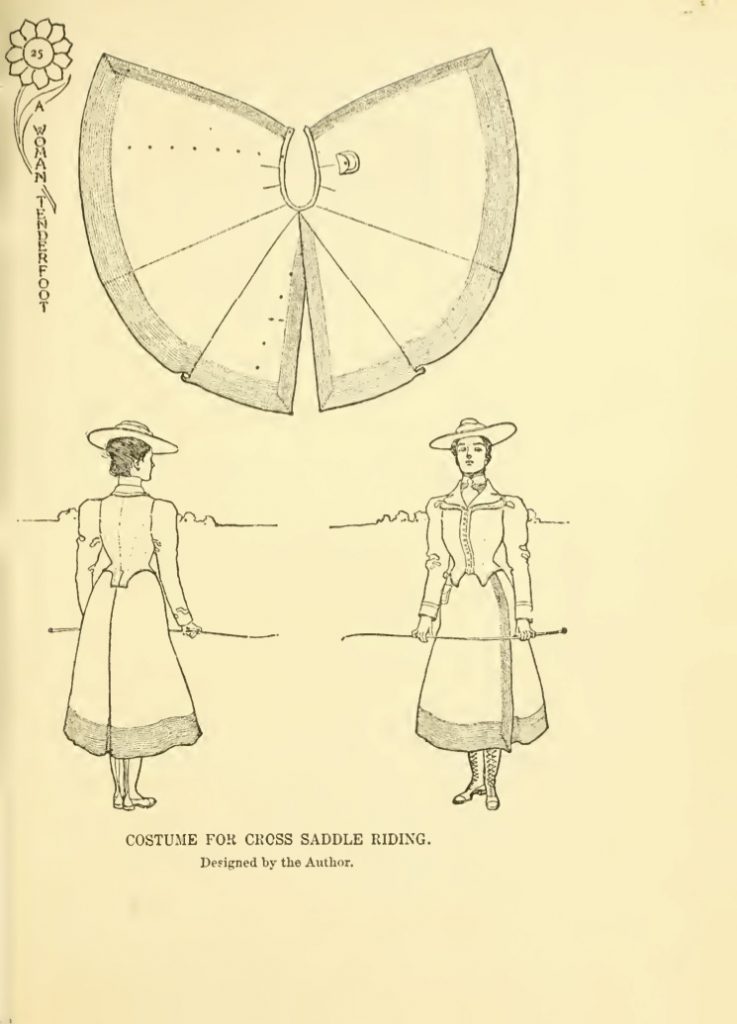

Like many other female travel writers of her day, Seton-Thompson often uses the popular persona of the new woman, a burgeoning archetype of the late-19th century and the early-20th century, associated with physical mobility, financial independence, and suffrage. From the 1890s onward, ideals of the new woman challenged older Victorian ideals of femininity that restricted physical and social mobility for women (Nelson ix). A lifelong suffragist and the head of the Connecticut Women’s Suffrage Association, Seton-Thompson conveys an interest in female emancipation from restrictive gender roles in A Woman Tenderfoot. Lucinda H. MacKethan emphasizes Seton-Thompson’s rebellious attitudes towards gender conventions in A Woman Tenderfoot, noting her “lady daredevil” persona (179), her self-designed riding costume that allowed her to avoid riding side-saddle, and her advice to female readers to make sure to hire a male cook when travelling so as to avoid such duties (178). MacKethan also observes that A Woman Tenderfoot established its author as part of a group of “literary outdoorswomen” who “capitalized on the popularity of western entertainments featuring women such as Annie Oakley,” the famous American sharpshooter (178).

It is important to remember, however, that Seton-Thompson’s work shows some of the classic conflicts and complexities of women’s travel writing. For example, she frequently asserts novel messages of female independence, while also regularly evoking traditional imperialist ideals that relate territorial expansion to cultural progress. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Canadian readers would have been well aware of the cultural stakes of this motif of a young woman’s western journey that we see in A Woman Tenderfoot. Just as western travel in Canada evoked British imperialist expansion throughout western North America and beyond, it also suggested the burgeoning nationalism of a country trying to differentiate itself from Britain and the United States. And most importantly, such travel would have immediately called to mind the puzzling figure of the new woman, pushing physical and cultural boundaries. Thus, Seton-Thompson’s western Canadian journey combined with her new woman persona in A Woman Tenderfoot is likely to have made this text both familiar and surprisingly modern for readers at the turn of the twentieth century.

In a prefatory note to A Woman Tenderfoot, Seton-Thompson refers to her implied reader as “some going-to-Europe-in-the-summer-woman” (7) whom she encourages to “go west instead” (7). On the one hand, Seton-Thompson’s lighthearted address to the reader, along with this contrast between European travel and a camping trip out “west” (7), appears to be a defiant call to women readers to be more physically “robust” (22) and culturally unconventional. On the other hand, the author’s casual allusion to European travel nods to the relative privilege of her readers. By carefully appealing to (and even labelling) this readership, the author perhaps restricts her messages of women’s rights to a rather elite transatlantic demographic that already has access to forms of physical and social mobility. Furthermore, this idea of going “west” (7) as a way to escape social convention is actually a familiar imperialist motif relating to American frontier expansion (and the more general territorial expansion of white Anglo-Saxon cultures throughout western North America) at the time.

Imperialism, Nationalism, and Gender in A Woman Tenderfoot

Since the early 2000s, scholars have begun to explore the ways that Seton-Thompson’s work engages in a complex negotiation with discourses relating to imperialism, nationalism, and gender. Some read her work as endorsing both imperialist expansion and women’s rights. For instance, in her discussion of Seton-Thompson’s 1925 travel account ‘Yes, Lady Saheb:’ A Woman’s Adventurings with Mysterious India, Shealeen Meaney shows how Seton-Thompson taps into patriotic associations with the American wilderness, while at the same time pushing the boundaries of “American womanhood” (Meaney 770). In my research on A Woman Tenderfoot, I show how this book, along with other texts such as Duncan’s A Social Departure, celebrates American nationalism and imperialism by adopting familiar motifs of physical movement in the wilderness that are associated with masculine modes of heroism, patriotism, and imperialist ideals of cultural progress (Johnstone). I suggest that Seton-Thompson adopts physical motifs with the aim of “questioning ideas of gender and ethnicity that underlie imperialist discourses of frontier expansion” (Johnstone 173).

While I argue that Seton-Thompson ultimately tries to destabilize dominant imperialist assumptions in A Woman Tenderfoot (Johnstone 173), some scholars contend that her romanticized perspective on frontier expansion “undermines” (Kelley 363) the feminist intentions of her text. In her analysis of Seton-Thompson’s 1923 travel account, A Woman Tenderfoot in Egypt, Joyce Kelley argues that the author’s stereotypical portrayal of Egyptians as mysterious and exotic “undermines Seton’s feminist agenda” (Kelley 363). This apparent conflict between the promotion of women’s rights and the assertion of often racialized ideas of American nationhood and empire can also be seen in A Woman Tenderfoot.

It is of course tempting to find a definitive interpretation of Seton-Thompson’s political views in A Woman Tenderfoot. However, it is perhaps more important to consider how the conflicting meanings in her text would have both expressed and challenged attitudes held by many of her readers.

The Representation of Indigenous People in A Woman Tenderfoot

“Five Feet Full in Front of Us, They Pulled Their Horses to a Dead Stop” by E. M. Ashe, in Seton-Thompson, 239.

Both Seton-Thompson and her husband have been criticized for their lack of cultural sensitivity towards Indigenous cultures. For example, in a study of North American youth groups, Pauline Turner Strong argues that popular groups such as the Boy Scouts have a history of reducing Indigenous cultures to performable roles and activities that are enacted by non-Indigenous children, thereby “reinforcing racial differences, entitlements, and hierarchies” (201). Strong notes how both Seton-Thompson and Ernest were involved in designing “traditions inspired by [Indigenous] rituals and symbols” (206) for the Camp Fire Girls.

Margaret Atwood suggests that Ernest’s allusions to Indigenous cultures in his Woodcraft Indians organization, while understandably inviting criticism for being “naive” and “sentimental” (60), may have promoted some curiosity and respect for such cultures, which both influenced the Boy Scouts and also ironically contributed to Ernest being excluded from the organization by more militaristic figures such as Robert Baden-Powell and Theodore Roosevelt (46-47). It is useful to consider if this naive sentimentality towards Indigeneity may emerge in A Woman Tenderfoot, which was published just one year before the formation of the Woodcraft Indians group. Strong’s reminders of the cultural appropriation associated with such wilderness groups should also alert us to Seton-Thompson’s potential reliance on racial stereotypes.

The most direct and also disturbing representation of Indigenous people in the book occurs in chapter 12. In this chapter, Seton-Thompson describes a trip to an unnamed American location where she visits the burial ground of a local Native American tribe. She refers to the tribe somewhat mysteriously as “Asrapako or Raven Indians” (218) and says that the location is “not such a far cry from the Rockies” (218). She also mentions evasively that it may have been somewhere in Montana (243). The vagueness of this chapter leaves many unanswered questions about the specific people and location she actually visited. She recounts visiting a local above-ground Indigenous cemetery where several shrouded bodies hang from trees. She describes a fellow traveller as disturbing one of the shrouded bodies, and she also refers to herself as “vandal enough to accept” (233) several pieces of jewellery from the body (233). Shortly thereafter, they are confronted by Indigenous men on horseback who remind them not to disturb anything. She conceals the jewellery and says that the men “slowly rode away, and with them the passive elements of a tragedy” (242). Seton-Thompson’s description of herself as a “vandal” (233) and her observation “that Indians are emotional creatures like ourselves” (235) reveal some awareness of the racism that she participates in at this point in her trip. However, she passively accepts the stolen property and ends the chapter on an upbeat note, avoiding any serious reflection on the incident. This troubling chapter sheds light on the fraught and often contradictory representations of westward expansion, gender, and race in women’s travel writing of the time.

Feminism and Performance in A Woman Tenderfoot

Work on women’s travel literature (Mills; Pratt; Smith) and women’s travel literature in Canada (Buchanan et al.; Grace; Johnstone; Roy) often incorporates feminist theoretical perspectives into its literary analysis. Autobiography theorist Sidonie Smith clarifies the ways that travel and representations of travel have historically been gendered. She observes that “in the process of becoming ‘men,’ travelers affirm their masculinity through purposes, activities, behaviors, dispositions, perspectives, and bodily movements displayed on the road, and through the narratives of travel that they return home to the sending culture” (ix). She then asks: “What does it mean for a particular woman to gain access” (x) to what she calls the “individualizing journey” (xi) of travel?

Much scholarship on women’s travel, including that of Smith, is inspired by feminist performativity theorist, Judith Butler. Performativity, according to Butler, means that representations of the body are inevitably gendered in a way that is socially constructed, despite often seeming natural (Butler). In the work of Seton-Thompson, the female body is represented in physical situations typical of “the masculinist literature of wilderness adventure stories” (Grace xxxviii) of her day (Johnstone). In particular, Seton-Thompson and other women travel writers of her time seem to be physically performing these masculinist roles in a way that both legitimizes their journeys and also challenges the very gendered stereotypes that they are performing (Johnstone). The following section of this chapter looks closely at select passages of A Woman Tenderfoot (in which Seton-Thompson describes her physical movements) in order to gain insight into the feminist implications of her travels.

Research Questions for A Woman Tenderfoot

- Take a look at the train journey documented at the beginning of Sara Jeannette Duncan’s A Social Departure (1890). What are the similarities to A Woman Tenderfoot? Do you notice any differences in regards to how Duncan discusses topics like gender, race, nation, and empire? Are there any indications of the authors’ differing nationalities?

- On page 293 of A Woman Tenderfoot, Seton-Thompson tells a story that is specifically set on a train. How does she choose to engage in this familiar motif of the westward train journey in Canada? How does she use humour in this chapter?

- Do some research on groups such as the Camp Fire Girls, the Woodcraft Indians, the Boy Scouts, and the Girl Scouts. In what ways were these organizations involved in broader cultural movements or ideas such as women’s rights, militarism, environmentalism, or cultural preservation? How would a text like A Woman Tenderfoot have potentially contributed to organizations like the Camp Fire Girls and the Girl Scouts?

Works Cited

- Atwood, Margaret. Strange Things: The Malevolent North in Canadian Literature. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995. Print.

- Duncan, Sara Jeannette. A Social Departure: How Orthodocia and I Went Round the World By Ourselves. New York: D. Appleton, 1890. Print.

- Grace, Sherrill. “A Woman’s Way: From Expedition to Autobiography.” Introduction. A Woman’s Way Through Unknown Labrador. 1908. By Mina Benson-Hubbard. Ed. Grace. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 2004. Print.

- Johnstone, Tiffany. “Frontiers of Philosophy and Flesh: Mapping Conceptual Metaphor in Women’s Frontier Revival Literature, 1880-1930.” Diss. University of British Columbia, 2012. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 14 Oct. 2017.

- Kelley, Joyce. “Increasingly ‘Imaginative Geographies’: Excursions into Otherness, Fantasy, and Modernism in Early Twentieth-Century Women’s Travel Writing.” Journal of Narrative Theory 3 (2005): 357–72. Web. 17 Oct. 2017.

- Meaney, Shealeen. “‘In My American Fashion:’ National Identity, Race, and Gender Tourism in Select Works by Zora Neale Hurston, Grace Seton-Thompson, and Zatella Turner.” Women’s Studies 7 (2009): 765-90. Web. 17 Oct. 2017.

- MacKethan, Lucinda H. “Grace Gallatin Thompson Seton (1872-1959).” Legacy: A Journal of American Women Writers 27.1 (2010): 177-94. Web. 17 Oct. 2017.

- Seton-Thompson, Grace Gallatin. A Woman Tenderfoot. New York: Doubleday, 1900. Internet Archive. 2009. Web. 12 Oct. 2017.

- Strong, Pauline T. “Cultural Appropriation and the Crafting of Racialized Selves in American Youth Organizations: Toward an Ethnographic Approach.” Cultural Studies – Critical Methodologies2 (2009): 197-213. Web. 17 Oct. 2017.

©

©