Diversifying Theory

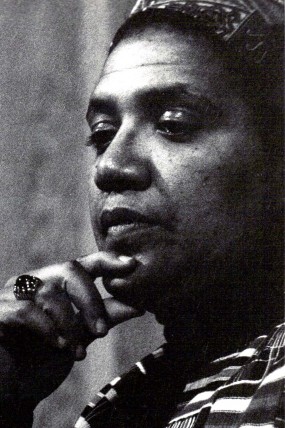

Audre Lorde, 1980. Photo by K. Kendall . CC BY 2.0

Beginning in the 1960s, and especially by the late 1970s, feminists began to consider the mutable boundaries of feminism and the plurality of female identities. A new wave of feminists—particularly ones who were marginalized by the paradigms of the previous waves—began to focus on women as a diverse group impacted by issues of ethnicity, class, and sexual expression, as well as economic, social, and cultural differences. This wider and more diverse perspective led to a multiplicity of discussions under the banner of feminism.

Writers of colour, such as black lesbian feminist Audre Lorde (1934–1992), argue that second-wave feminism contains discriminatory perspectives that understated the important differences between people within the feminist project. As Lorde discusses in a 1980 address,

By and large within the women’s movement today, white women focus upon their oppression as women and ignore differences of race, sexual preference, class, and age. There is a pretense to a homogeneity of experience … that does not in fact exist. (116)

Since the 1980s, a growing international critique of feminism has emerged, arguing that second-wave feminism was too restrictive and represented primarily the interests of white, colonial/Eurocentric, middle- and upper-class women at the expense of the experiences and voices of minority and working class women. Writers such as bell hooks, Alice Walker, Himani Bannerji, and Lee Maracle pushed to open up the discourse to minority, racially, and ethnically marginalized perspectives, broadening who is represented within feminist critiques and conversations. For example, Lee Maracle’s I Am Woman offers reflections on the dialogue between race and gender, particularly the relationship between Indigenous heritage and feminism.

Many contemporary Canadian writers, such as Dionne Brand, Nalo Hopkinson, Larissa Lai, SKY Lee, M. NourbeSe Philip, Eden Robinson, Marie Annharte Baker, and Rita Wong, continue to explore the intersections between racism, classism, and sexism, and their effects on gender. These writers are in dialogue with international conversations surrounding the interplay between racial and gender-based discrimination, in order to expand feminist interests to issues of class, ethnicity, and processes of racialization for women. The focus is not only on how individual and social differences complicate and nuance discussions of power and discrimination, but also to articulate the intersectional common grounds between those who are oppressed.

Despite many differences in experiences, third-wave feminists remain aware of the multiple ways in which oppressed groups are interrelated, which is known as intersectionality (Crenshaw 1243). A nuanced feminist engagement with inequity requires the recognition of the complexities of these relations. Thus, as Larissa Lai argues,

Those of us who want voice and rights for women need still to keep fighting for them. We also need to continue to work on the narrative of what equality, justice, rights or voice might mean and what they might look like …. all the racism, sexism, classism and homophobia that are built into Western culture are alive and well but, at least in Canada, we’ve carefully crafted ways to avoid talking about these things while still enacting their ancient and deeply entrenched structures. (n. pag.)

Lai’s point about politeness as an avoidance strategy is worth unpacking. In Canada we pride ourselves on being polite—in fact, you could call our politeness a part of our national self-image. One of the ways that discourses of politeness are used within Canada is to silence women who are interested in questions of sexuality and gender under the premise that asking about such things makes people uncomfortable. The unofficial push to politeness can make it feel like discussing issues of equality, social justice, or voice is impolite, or not the kind of things nice Canadians do.

Third-wave feminism seeks to unearth these entrenched structures and cultural mores; one way of doing this is through literature, which can help us see our contemporary and past societies anew, and to envision a future in which power struggles no longer feature in the discussion of gendered experiences. Contemporary authors like Dionne Brand, Nicole Brossard, Anne Carson, Nalo Hopkinson, Larissa Lai, and Lee Maracle, among many others, do just this in a huge variety of innovative ways in their writing and criticism.

Works Cited

- Crenshaw, Kimberle.

Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.

Stanford Law Review 43.6 (1991): 1241–99. Print. - Maracle, Lee. I Am Woman: A Native Perspective on Sociology and Feminism. Vancouver: Press Gang, 1996. Print.

- Lai, Larissa.

An Interview with Larissa Lai.

By Gillian Jerome and Meredith Quartermain. CWILA: Canadian Women in the Literary Arts. N.d. Web. 18 Sept 2013. (Link) - Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. 1984. Berkeley: Crossing, 2007. Print.

©

©