This guide draws attention to the centrality of gender and sexuality in the discussion of Canadian literature and culture, and to the kinds of criticism done within the journal Canadian Literature. Understanding how gender and sexuality are constructed is a central scholarly concern in understanding Canada’s national and literary imagination. To see this, we can begin by considering early propaganda images that constructed Canada’s West as an idealized and harmonious community awaiting settlers.

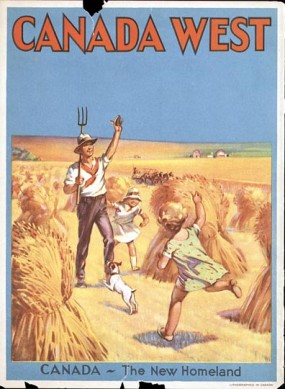

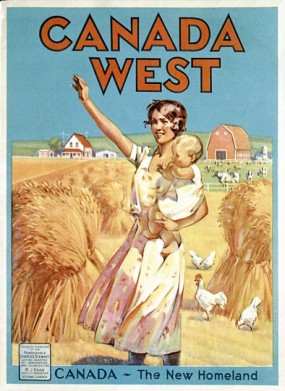

Scholars of literature love reading propaganda posters because they reveal so much about the assumptions that helped to create Canada as an imagined, gendered, and racialized community. In order to sell Canada as an immigrant community to potential Northern European and Western American settlers in the 1920s, the acting Minister of Immigration and Colonization, W. J. Egan, issued propaganda posters about the abundance and potential of Canada’s West in Canada West magazine. Figures 1 and 2 are settlement propaganda posters. Within the images is a promise to new settlers that living in Canada will be comfortable, and that families will have bright futures. Canada is depicted as having abundant farmland, where white settlers will find a happy hearth and home. The idealized settler, according to these posters, is young, healthy, and fruitful—the northern European everyman; it is the relationship between their implied industry, understanding of modern farming techniques, and ability to endure the Canadian climate with ease, as well as their willingness to have big families, that makes these young pan-Europeans ideal subjects for The New Homeland.

The secondary, but no less important, promise of Figures 1 and 2 is that Canada’s West is a gendered utopia. Canada’s West, with its agrarian economy, will have clearly defined gender roles and expectations, and adhering to these roles will help the settlers thrive. The father is in the field, working the land, and providing for his young wife and children. The wife is coming out to the field, perhaps from the homestead, with a young babe in her arms, to greet her husband. The children, and small dog, are excited to welcome their father and provider back from the field. Even the lighting of the image promises happiness, with its soft tones, clear blue skies, and seemingly endless prairie horizons. The image, moreover, is of bounty obtained by order. The wheat is neatly stacked, with a combine visible in the background. The livestock are safe in their pen, and the chickens are feeding themselves by grazing on the leftover wheat. Coming to Canada, the propaganda posters imply, allows white families to settle in a bountiful land of opportunity, with clear gender norms, where the patriarchal family structure is as natural and easy to cultivate in Canada’s pliable lands as the wheat and livestock.

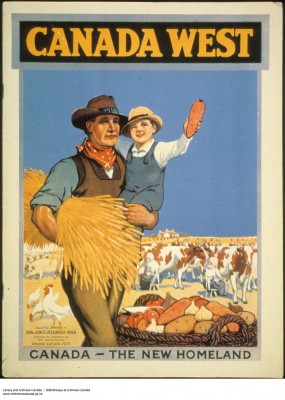

Figure 3: Canada —The New Homeland (1925). Minister of Immigration and Colonization. Library and Archives Canada, no. 2958967

Feminist scholarship in Canada has drawn attention to the interconnected nature of race, class, gender, and sexuality in constructing the idealized settler-nation of Canada. Consider, for example, the gender assumptions implicit in Figure 3, where a slightly older, pan-Northern European man is holding a sheath of unbound wheat in his right arm and a young, healthy son in his left. The son is holding up a rather large carrot, triumphantly, looking up to the sky while the father’s gaze is looking steadily forward. Propaganda images of the 1920s Canadian men are frequently shown with and around children, in a land of fecundity. The image implies an idealized order, with the father working and spending time with his child because the women of the farm are tending to the cows.

Figure 3 reinforces the idea that the happiest immigrants are men who can produce sons who will one day take up the call to farm the land themselves. This idea of men passing on the farm to their sons is paradigmatic of patriarchy, with the father existing as the head of the home and the son as the expectant inheritor of his power and wealth. The child is holding a carrot, a product of the land he is to one day own and farm; his prospects are limited, to some degree, by the gender expectations he is born into and being groomed to accept and perform. While the men can look forward, focused on his future, the women are looking away, down at the cows utters, milking and tending to the domestic. The women in the picture are hard to find; their white shirts allow them to blend into the livestock they are milking. While the woman in Figure 2 is happy, expectant, and holding a child in her arms that implied futurity, these faceless women in Figure 3 are hunched over, tending to livestock. Opportunities for settler women within Canada’s West seem constrained to the home and hearth, whether they are young or old. Women are to be happy tending the land, producing children, and supporting their husbands. One of the things that feminism has done is expand opportunities for women beyond having children and caring for the domestic sphere. Implicit in the backlash against feminism is a desire to return to the utopian ideal of images like the ones from the Canada West series. Such a desire may be based on nostalgia for a simpler past.

Reading images in this way is an example of feminist criticism. By examining representations of gender in cultural works such as literature, we can begin to see the ways in which social roles are constructed along gender lines. While some conservative critics see feminism as being either over or unneeded in todays culture, this chapter explores why feminism is still important today, the role of gender in the formation of the Canadian literary canon, and Canadian Literature’s history with issues of gender and feminism.

©

©