Canadian Historical Overview

“Meeting of Fur Traders (1925) by Henry Sandham. Canadian Historical paintings 1534-1885 by Jefferys and Sandham, Library and Archives Canada, accession number 1996-282-11, C-000122

The development of cultures and nation states is characterized by migration (see Diamond and Wolf). With the advent of new technologies to connect people all over the world, such as airplanes and the Internet, this slow migration accelerated in the twentieth century, and continues to gather speed. This phenomena, also known as globalization, reflects the shift toward the colonial expansion of empires, starting in Canadian history with English and French colonization and continuing as well as in more contemporary forms of international immigration and trade.

While some thinkers consider globalization to have begun many centuries ago with the international trade of sugar, spices, fur, and slaves, others tie its inception to increased global migration. Still others use the term to refer to a more contemporary increase in the speed of movement of people and/or information.

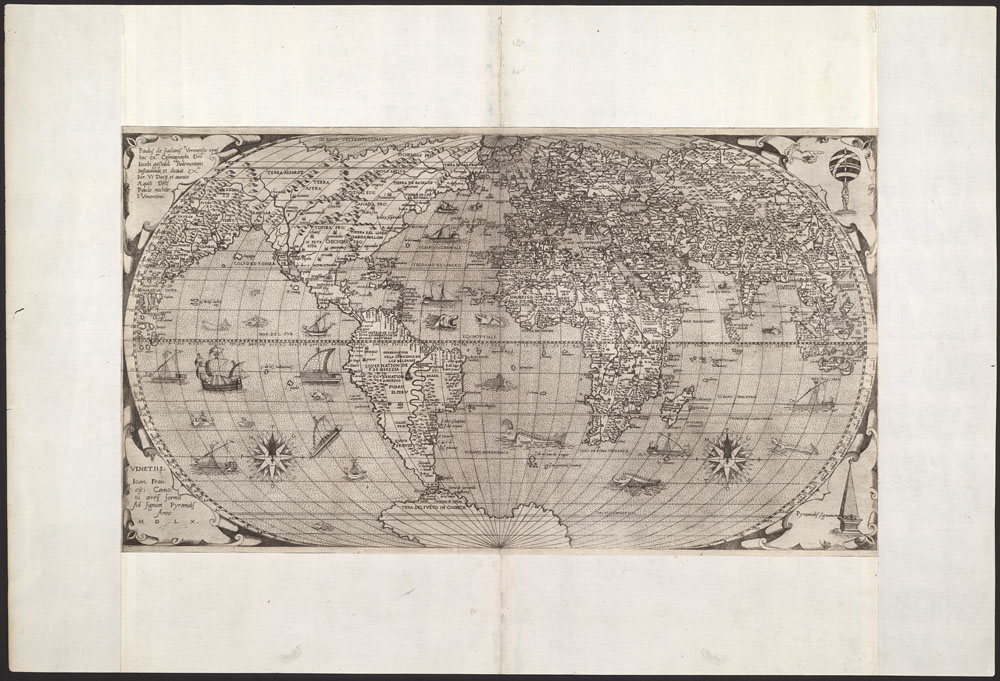

The territory now unified as Canada has seen First Nations, Russian, Spanish, French, British, and American claimants. Initially, Canada generally referred to the region along the St. Lawrence waterway and southern east coast. The name first appeared on an international map in 1547.

Also, while Canada

has had many origin stories, the term is now generally accepted to derive from the Huron or Iroquois terms for village (an-da-ta or ka-na-ta respectively), first recorded in the writings of Jacques Cartier in 1534 (Avis 110–11; New 173).

One of the first depictions of some now-Canadian territory on a world map (1560) Paolo Forlani and Giovanni Francesco, Library and Archives Canada, accession number 878011 CA, e006581135-v8

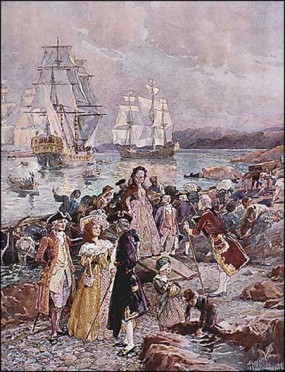

“The coming of the Loyalists, 1783 by Henry Sandham (1925) Library and Archives of Canada, accession number 1996-282-7, C-000168

Immigration to Canada

The first immigration to what is now Canada was to Newfoundland, to the Viking village at L’Anse aux Meadows, in 1000 CE. However, it wasn’t until much later that stable settlement led to local cultural development.

During the late 1700s and early 1800s, settlers displayed a form of nationalism in their colonial fealty to France and England, as well as a growing sense of connection to what was already being called Canada. A Canadian changed from meaning anyone living in the region to someone of European origin from Upper and Lower Canada and later Canada West and East. See Canada

and Canadian

in Walter S. Avis’ Dictionary, as well as the good summary entry in W. H. New’s Encyclopedia, for more on these changing usages.

Establishing the Dominance of English in Canada

A key shift in perceptions of Canada came with the Battle of the Plains of Abraham (13 September 1759) just outside Quebec city. In this battle, the British secured a key position, forcing France to slowly cede most of its possessions over the next four years.

“The Death of General Wolfe (1857) by Alonzo Chappel. Library and Archives Canada, accession number 1970-188 PIC 00096, C-042249

Despite this victory, success in national politics has often required the accommodation of the aspirations of the French speakers in Canada, since they have always formed the largest group of non-English speakers in the country. Other cultural and linguistic groups, including Indigenous peoples, were expected to assimilate to the notion of Canada as British.

Works Cited

- Avis, Walter S., ed. A Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles. Toronto: Gage, 1967. Print.

- Diamond, Jared. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York: W. W. Norton, 1997. Print.

- New, W. H. ed. Encyclopedia of Literature in Canada. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2002. Print.

- Wolf, Eric. Europe and the People Without History. Berkeley: U of California P, 1982. Print.

©

©