A form of nationalism particularly relevant to the study of Canadian literature is cultural nationalism, which argues for the support, recognition, and preservation of cultural institutions and products as necessary elements of national identity.

This nationalism has sometimes been driven by a desire for self-articulation and sometimes by cultural protectionism.

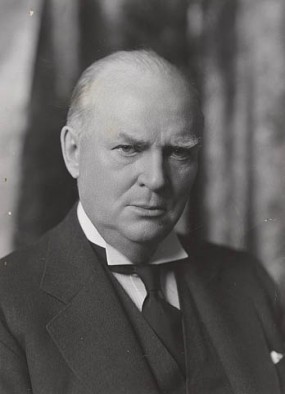

R. B. Bennett. Library and Archives Canada, inventory number 357-1, accession number 1989-565, e000009295

Canadian nationalism has always had one eye on the US—powerful neighbour to the south. In Canada, cultural nationalism has played out most clearly in government-initiated mandates to create national institutions such as the CBC, the CRTC, the National Library, and the Canada Council for the Arts, which provides funding support for a wide range of cultural expression. The continued support of such national institutions is often under debate.

An early act of cultural nationalism came in 1929, with the development of radio technology. The Canadian government created a Royal Commission to look into the effects of foreign programming on the developing Canadian psyche.

The commissioners took a decidedly nationalist stance when they concluded in the Report of the Royal Commission on Radio Broadcasting (1929), commonly referred to as the Aird Report, that such programs

have a tendency to mould the minds of Canadians (particularly youth)

to ideals and opinions that are not Canadian… [and] suggested that broadcasting shouldfoster a national spirit and interpret national citizenshipandpromote the unity of the nation.(Aird, 1929 [qtd. in Stanbury n. pag.])

Prime Minister R. B. Bennett, in establishing the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission (the precursor of the CBC) in 1932, defined its role as the

complete control of broadcasting from Canadian sources … communications of matters of national concern … diffusion of national thought and ideals … [to foster] national consciousness … [and to strengthen] national unity.(House of Commons Debates, May 18, 1932 [qtd. in Stanbury n. pag.])

Canadian culture and national identity are inextricably linked in Bennett’s statement.

Nationalist Confidence

As the nation grew in confidence, writers actively sought to create new and innovative forms of poetry and prose that adequately reflected the post-war Canadian context in which they were born.

Significantly, following World War II, writers, politicians, and citizens alike expressed the need for stronger expressions of cultural nationalism. In poetry circles, this took the form of a debate around native

and cosmopolitan

forms of writing, as A. J. M. Smith termed them in The Book of Canadian Poetry (1943).

For Smith, the native

group of poets considered what was individual and unique in Canadian life

and subsequently risked writing parochial, overly sentimental nationalist poetry (5).

Conversely, he saw the work of the cosmopolitans

to have made a heroic effort to transcend colonialism by entering into the universal, civilizing culture of ideas

(5). Others disagreed with Smith’s conception of nationalist writing and saw Canadian-focused poetry to be vital for the development of national arts.

The Massey Commission

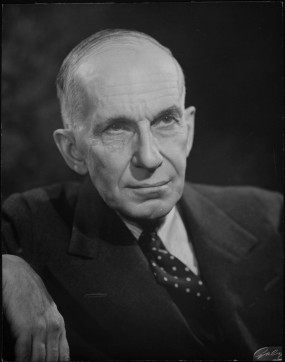

Vincent Massey, chair of the Massey-Lévesque Commission (1954). Gabriel Desmarais, Library and Archives of Canada, PA-215425

In 1949, Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent created a Royal Commission to assess the state of the arts, letters, and sciences in Canada. The agenda of the official Order in Council creating the Commission was one of cultural nationalism:

it is desirable that the Canadian people should know as much as possible about their country, its history and traditions; and about their national life and common achievements … it is in the national interest to give encouragement to institutions which express national feeling, promote common understanding and add to the variety and richness of Canadian life, rural as well as urban. (“The Order of the Council” xi qtd. in National Development)

After a year of public hearings in 16 cities, with 1200 witnesses reporting on the state of culture and science in Canada, the Commission issued their final report, now remembered in English Canada as the Massey Report.

The Report focused on the need for an increase to government funding and patronage, and argued that because culture plays a critically important role in nation building, the federal government has an obligation to better support its development:

If we in Canada are to have a more plentiful and better cultural fare, we must pay for it. Good will alone can do little for a starving plant; if the cultural life of Canada is anaemic, it must be nourished, and this will cost money. (National Development 272 no. 5)

The Massey Report operates from a principle of fear of American cultural annexation—of becoming subsumed into American cultural expressions rather than remaining distinct from them—and propounds the economic as well as social need to strengthen Canadian culture in the face of American cultural dominance.

The findings of the Massey Commission led to the establishment of the Canada Council for the Arts, among other national institutions. Some would argue that it also promoted a somewhat narrow view of Canadian culture.

This narrow view was also reflected in the rising numbers of anthologies, for which Carole Gerson provides a helpful overview in her article

(90–94). However, Gerson arguesThe Most Canadian of all Canadian Poets

: Pauline Johnson and the Construction of a National Literature

The overtly nationalist agenda of these various undertakings—to determine the uniquely Canadian features of Canadian writing—was underpinned by the academic high modernism in which their editors and authors (almost exclusively male) had been trained. Scorning romanticism and sentimentality, they valorized detachment, alienated individualism, elitism and formalism over emotion, domesticity, community, and popularity, a binarism that implicitly and explicitly barred most of Canada’s women writers from serious academic consideration. The literary history that these projects constructed was based not on what the majority of Canadians had in the past written and read, but on the elitist vision that prevailed among Canadian scholars and critics. (91–92)

The growth in nationalist pride, therefore, was expressed both in society and in literature in quite limited, often masculine and Eurocentric terms.

Nationalist Criticism

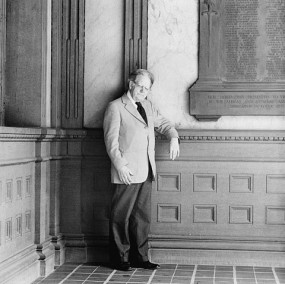

Northrop Frye (1984). Harry Palmer, Library and Archives Canada, accession number 1987-025 NPC, PA-182431

Canadian literary and cultural critics have struggled to define what, exactly, makes Canadians Canadian and, in turn, what is distinctive about our literature and culture.

One idea is that Canada is defined by its anxieties over its own existence. A popular example of this kind of criticism is Northrop Frye’s Literary History of Canada (1965), where he introduces the idea of the garrison mentality. Frye notes that Canadian settler communities tended to be “small and isolated communities surrounded with a physical or psychological frontier

(350–51) that, they worried, was always on the brink of consuming them and their culture. The feeling of being surrounded by what Frye calls a formidable physical setting

lead settler communities to develop a garrison mentality, where closely knit communities felt that they needed to collectively struggle against the hostile environment. This struggle, in turn, began to define the settler experience.

Margaret Atwood extended Frye’s ideas in her influential book, Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature (1972). In this book she suggests the central symbol that unites Canadians is that of the multi-faceted and adaptable idea

(32) of survival:

Our stories are likely to be tales not of those who made it but of those who made it back…. The survivor has no triumph or victory but the fact of his survival…. A preoccupation with one’s survival is necessarily also a preoccupation with the obstacles to that survival. (33)

Margaret Atwood (1972). John Reeves, Library and Archives Canada, accession number 1980-194 NPC, e008295854-v6

In Survival, Atwood illustrates different victim positions

(36–39) throughout a wide variety of Canadian literary texts, always affirming the central Canadian concern with survival.

While Frank Davey and others have termed Frye’s and Atwood’s approach thematic because of their focus on distinctively Canadian themes, symbols, and myths, both can be seen as structuralist—as focused on overarching, broad patterns rather than close readings. These attempts to define a national identity or psychosis

(Davey 6) seen in literature can reveal important patterns of representation, but this perspective can also mean that the derivative and the mundane can receive the critic’s attention while the unusual or original do not

(7).

Atwood’s positions, like Frye’s four-fold system in his Anatomy of Criticism, are intended as a model or verbal diagram

to articulate the skeleton of Canadian literature

(39; 40). These approaches have benefits, but are also problematically reductive. See Davey’s influential rebuttal of the thematic approach published in Canadian Literature, Surviving the Paraphrase

for more.

The debates surrounding thematic criticism emphasize the importance of interweaving levels of analysis, so that the original details of individual texts inform broader critical patterns and perspectives.

Works Cited

- Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters, & Sciences, 1949–1951. Report. Ottawa: King’s Printer, 1951. Collections Canada, n.d. Web. 25 May 2012.

- Royal Commission on Radio Broadcasting. Report. Ottawa: King’s Printer, 1929. Print.

- Atwood, Margaret. Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature. Toronto: Anansi, 1972. Print.

- Davey, Frank.

Surviving the Paraphrase.

Canadian Literature 70 (1976): 5–13. Print. (PDF) - Gerson, Carole.

Canadian Literature 158 (1998): 90–107. Print. (PDF)The Most Canadian of all Canadian Poets

: Pauline Johnson and the Construction of a National Literature. - Smith, A. J. M. The Book of Canadian Poetry. Toronto: Gage, 1943. Print.

- Stanbury, W. T.

4. The Legal Bases for Canadian Content Regulations.

Fraser Forum (Aug. 1998). The Fraser Institute, n.d. Web. 13 Aug. 2013. - Frye, Northrop.

Conclusion to the First Edition of Literary History of Canada.

[1965]. Northrop Frye on Canada. Ed. David Staines and Jean O’Grady. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2003. 339–73. Google Books. Web. 13 Aug. 2013.

©

©