Notre Dame Basilica in Place d’Armes, Montreal. Quebec has traditionally been a site of resistance to the idea of a homogenous Canada. “Basilica Notre Dame, Place d’Armes.” Alexander Henderson, Library and Archives Canada, item number 04, accession number 1963-058 NPC, PA-009191

In the 1960s and 70s, the unified vision of a culturally homogeneous nation run by elite white men was fractured by civil rights movements against racial discrimination, the women’s movement, and the Quiet Revolution in Quebec. The Quiet Revolution, which became noisier over time, led to the referendums on sovereignty in 1980 and 1995 because of the division between federalist and sovereignist political factions.

Between the world wars, women gained the right to participate in public office, and the feminist movement continued to critique social norms and celebrate autonomy. Likewise, the broader civil rights movement sought to liberate various marginalized groups from the powerful oppression institutionalized and socially accepted throughout colonial history.

This movement promoted diversity within the nation, a diversity that was not seen as divisive but as a greater celebration of its cultural richness.

Out of this approach emerged the dominant, and sometimes self-congratulatory, contemporary view of Canada as a multicultural nation that intervenes in the colonial patterns of the past in attempts to remodel the nation as diverse and postcolonial.

Multiculturalism stamp issued by Canada Post, 1990. Canada Post Corporation, Library and Archives Canada, R169-133-1-E, e000008435

Immigration

After the 1967 Immigration Act shifted the criteria for immigration from place of origin to assessments of education and skills, immigration increased from Asia, including refugees from wars in Korea, Vietnam, and Cambodia, and the Cultural Revolution in China. Immigration from the Caribbean, India, and Africa also increased dramatically.

Shortly after the new immigration policy was implemented, and in the wake of recommendations from the Bilingualism and Biculturalism Report (1969), the government decided to create a policy of multiculturalism (1971). This policy was implemented primarily in response to the adamant call for recognition and civil rights by Canadians whose ancestors were neither British nor French.

The policy of multiculturalism opened the door for social, political, and institutional recognition and promotion of the contributions of multiple cultural communities to the development of Canadian society.

Multiculturalism was adopted as official policy in a bilingual framework in 1971, and later in the broader Multiculturalism Act of 1988.

Redress

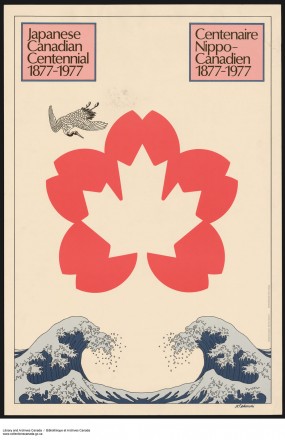

Japanese Canadians celebrated the arrival of the first Japanese immigrant to Canada in 1877. The event galvanized the community and helped contribute to the campaign of redress. “Japanese Canadian Centennial 1877-1977.” Library and Archives Canada, R11274-, accession number 00427, e010754632-v8

Multiculturalism is a concept many Canadians take pride in, even if it is sometimes less certain how well they practice it.

The Canadian government has recently made a concerted effort to enact the policy of multiculturalism as an affirmation of national, collective responsibility for all citizens. The processes of redress and reconciliation with Aboriginal peoples and Chinese and Japanese Canadians are examples of official acknowledgements of multiculturalism by the federal government.

These processes further affirm the diversity of ethnic and cultural backgrounds in Canada as positively contributing to the popular life of the nation, marking a dramatic shift away from the assimilationist views held by earlier nationalists, although such assimilationist views are still held by some. As Ven Begamudré states,

Maybe multiculturalism as an official policy hasn’t worked because people at the individual level have not become more tolerant. When you spit on a person or deny them an apartment because they are different from you, you have done society at large a fundamental injustice.(qtd. in Coleman 36)

Speculative Histories

Herb Wyile has written extensively on recent historical fiction in Speculative Fictions (2002). In this book, he shows how in representing history, such fiction opens up questions about who gets to write or contribute to understandings of the official record of history. Wyile observes that recent historical fiction in Canada shows an inclination toward the telling of untold tales (of indigenous peoples, immigrants, minorities, workers, and women)

(137).

By presenting untold stories, these works raise questions about knowledge, documentation, power, gender, and identity, and show how accepted understandings of the past can be opened up through alternative, previously misrepresented perspectives and silenced voices. These works ask us to engage with the

recognition, rather than suppression, of … forces involved in the negotiation of just what

Canadameans. (Wyile 110)

Historical fiction, by speculating about alternative understandings of historical moments, figures, and scenes, intervenes in the seemingly homogenous history inherited from racist, powerful institutions. These institutions can include governments, as well as literature and other social structures.

These approaches interject a multicultural polyphony of voices into the seemingly singular (white European male) voice of the nationalist past.

Works Cited

- Wyile, Herb. Speculative Fictions: Contemporary Canadian Novelists and the Writing of History. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 2002. Print.

- Coleman, Daniel. White Civility: The Literary Project of English Canada. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2006. Print.

©

©