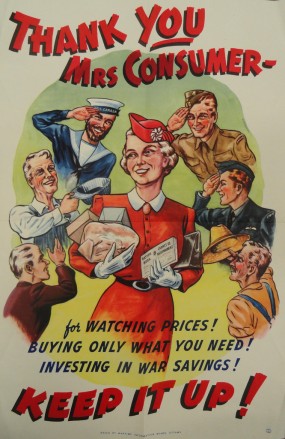

Mrs. Consumer poster, ca. 1944. Wartime Information Board, Ottawa. Deseronto Archives

Postfeminism and conservative feminism share an intellectual foundation but are different movements. Postfeminism is a critique of second- and third-wave feminism, while conservative feminism rejects the liberalism of second- and third-wave feminism. Conservative feminists argue that the age of high feminist activism ended in the 1970s, and that the feminist movement obtained its primary goals. They argue that the issues feminists are currently fighting for are unpopular and radical, and that embracing a liberal agenda led to the backlash against second- and third-wave feminism. Importantly, conservative feminists do not argue against the gains in the status of women, especially as those gains pertain to increased consumer choices for women and the right to increased political participation. What conservative feminists object to is the radicalization of feminism, and to the way that the mission of feminism expanded in the 1980s and 1990s to address issues of sexuality, reproductive choice, and diversity. As such, conservative feminists try to reconstruct the female subject in an idealized image, so that women can become ideal consumers and political subjects.

Conservative feminists frequently set themselves in opposition to revolutionary feminist politics. Conservative feminism embraces the idea that the ideal woman is one who desires to be desired, ideally by men, and who embraces their femininity and/or status as woman, wife, and mother. For conservative feminists such as Christiana Hoff Sommers, the feminist movement needs to return to its first wave. According to Sommers,

The feminist foremothers of the first wave, despite their personal limitations, were promoting universal human ideals. The right to vote, to be educated, to enter a marriage of equals, to flourish—these are not the special province of white women, middle-class women, American women, or Western women. They are rights that belong to human beings everywhere. (69–70)

Conservative feminists agree that first-wave feminism was imperfect, that it could be racist, and that it was at times classist. They counter that attempts to improve upon first-wave feminism that are rooted in Marxism, critical race theory, or queer theory are doomed to fail because they are too radical to be embraced by the general public. For conservative feminists, second- and third-wave feminism are primarily academic movements that will not gain and sustain political traction because they are too radical.

A busy intersection in Manhattan, 16 July 1936. Berenice Abbott, public domain. New York Public Library: flickr

Sommers’ discussion of universal rights and values of women as human beings is a direct challenge to third-wave feminism and its discussion of intersectionality. Intersectionality is the idea that issues like race, gender, sexuality, and class are interdependent. Women and men can experience intersecting discrimination based on things like race, gender, sexuality, and class. The term “intersectionality” comes from feminist critical race theorist Kimberle Crenshaw. Crenshaw argues that the issue with identity politics is not that it does not empty identity categories like race, gender, and class of meaning, but “that it frequently conflates or ignores intragroup differences” (1242). For Crenshaw, there is not one, universal, category of woman, man, black, or white, but intersecting categories of identity, and to understand how oppression works it is important to see how intergroup differences impact subjectivity.

A central concern of third-wave feminism is that issues gender inequality cannot be separated from issues of race and class. Conservative feminist argue that women are already equal to men in the West, and they see one of the goals of feminism as emptying out categories like race, class, and gender of meaning while retaining the ideals of femininity and masculinity. In this way, Sommers’ reference to feminist foremothers is being used to imply that the early feminists were primarily women and mothers, and that the race and class of these women is secondary to their (moral) status as women and mothers.

Postfeminism

Some might say that postfeminism is not a real movement, but rather a media and publishing invention, since individuals or groups rarely self-identify as postfeminists. Often, the term postfeminist is used as a criticism against people or cultural works that are deemed to mistakenly believe that the goals of the feminist movement have all been achieved. In this usage, the term postfeminism carries with it the connotation that someone’s thinking is naïve, or perhaps under-theorized.

Since many feminists argue that conservative feminism is a co-option and betrayal of feminist activism, more radical feminist often dismissively describes conservative feminists as postfeminists. However, not every person or work described as postfeminist is necessarily conservative. In fact, the first uses of the term “post-feminism” come from the radical left in France during the student protests of the late 1960s. These women were protesting what they saw as the gender essentialism of what would come to be known as French feminism. Elizabeth Wright’s Lacan and Postfeminism is a good introduction to this more radical, postmodern critique of feminism.

Within all of feminist theory, postfeminism is perhaps the hardest term to define objectively. Feminism itself is rather difficult to define, as the feminist movement never represented a uniform set of ideas, goals, or terms; likewise, saying what comes after feminism is difficult because it is often unclear what is being rejected.

bell hooks, 1 Nov 2009. Location unknown. Public domain: Wikimedia Commons

To see why this is the case, consider two fairly strong definitions of feminism. In her introduction to second-wave feminism, Joanne Hollows argues that feminism “is a form of politics which aims to intervene in, and transform, the unequal power relations between men and women” (3). The key term in Hollows definition is transform. Feminism is a project that aims to identity, intervene in, and transform unequal power relations between men and women. According to feminist and theorist bell hooks, “feminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression” (1). Hollows’ definition overtly names men and women as the subjects of feminism, where hooks’ definition is not concerned with equality between the sexes but with liberation. For feminism to obtain its end, according to hooks, sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression would have to be at an end. By either of these definitions, to have a postfeminism, we would either have had to arrive at a point in history where power relations between men and women are as equal as they are ever going to be, or we would have had to have arrived at a time when the goal of ending sexism and exploitation no longer seems attractive given the cost of obtaining such a goal.

Postfeminism is not something that came after the mission of feminism was accomplished, since such a definition would have to assume that the aims of third-wave feminism are not feminist and that women and men are equal. Further, such a definition would have to assume that goals like creating income equality between men and women, ending the baby penalty for women, or eliminating rape culture are not sufficiently feminist goals. Rather, postfeminism is something that came about, largely, in relation to the backlash against feminism in the 1980s, something Susan Faludi discusses in her work Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women. After the backlash, many women were hesitant to use the term feminist because they worried that it carried radical connotations. Likewise, conservative feminism came about because conservative women decided that feminism was dead. By this they mean that the feminist’s protests for equal rights of the 1960s and 1970s is now over and that such protests “won” the culture wars.

This chapter will explore some of the critical discussions and complex interactions between the concepts of postfeminism and conservative feminism.

Works Cited

- Crenshaw, Kimberle.

Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.

Stanford Law Review 43.6 (1991): 1241–99. Print. - Faludi, Susan. Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women. 1991. New York: Three Rivers, 2006. Print.

- Hollows, Joanne. Feminism, Femininity and Popular Culture. New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Print.

- hooks, bell. Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics. Cambridge: South End, 2000. Print.

- Wright, Elizabeth. Lacan and Postfeminism. Cambridge: Icon, 2000. Print.

- Sommers, Christina Hoff. Freedom Feminism: Its Surprising History and Why It Matters Today. Lanham: AEI, 2013. Print.

©

©