“The Finding of the Tell-Tale Bullet” (1902), photographers unknown. A part of the murder investigation into V. Fournier and E. Labelle in the Yukon.

Library and Archives Canada. Accession number 1996-400 NPC, A205090.

Think of close reading as similar to a criminal investigation in which we, as readers, move slowly through the language and forms of the text, working through suggested connotations, subtle connections, and implications of terms and images. Our goal is to unravel the subtle riches of expression, to solve (or glimpse) the mystery.

This does not mean that there is one right, coherent, or even fully intended meaning to a text. However, writers do craft language to imply connections—and close reading allows us to explore those connections.

Rather than right or wrong readings, there are good readings (which look carefully at the complexities of the language, showing why some meanings are likely intended, and others, perhaps not) and bad readings (which ignore the details).

Close readings occur throughout academic work, focusing on shorter, important passages or key images in various forms of literature like poems, novels, short stories, and plays. This strategy is a crucial part of developing and supporting an argument about the given work.

How Is Close Reading Like a Murder Investigation?

In some ways, close reading can be seen as analogous to those scenes where the detective searches a room she has never been in for clues.

She is seeking to fit apparently random bits of paper, computer files, broken dishes, bloodstains, etc. into some sort of story of what might have happened. That story is necessary in order to make sense of the situation.

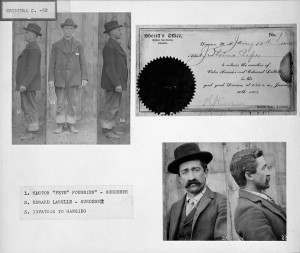

Murderers Victor “Pete” Fournier (upper) and Edward Labelle (lower) with the invitation to their hanging in the Yukon, January 1903.

Library and Archives Canada, accession number 1996-400 NPC, PA-205087 90

In fact, we could argue that the pleasure we get out of reading murder mysteries and other popular genres like thrillers and spy stories is that they take a confusing reality and produce one clear narrative, a guilty party, and a solution for us at the end.

©

©